In September 2021, the EU Parliament has rejected plans to reserve five specific groups of antibiotics for use in humans and largely ban them in animals. Developments concerning the avian flu and African Swine Fever are still closely monitored in the EU. At national level, a pig backlog and shortage of CO2 and workers are […]

Our Works

Are futures the future for farmers?

An evaluation of agricultural futures as a risk management tool in the context of price volatility

Agricultural markets have an inherent tendency towards instability. This is mainly because the supply and demand market fundamentals of the agricultural sector are characterised by rigidity, as food is a basic necessity for consumers and agricultural production is seasonal. Producers of agricultural commodities are therefore much more vulnerable to price shocks than other industrial sectors. [1]

This vulnerability became particularly clear during the fallout of the global financial crisis in 2008, which initiated a period of high variations in the prices of agricultural products. As a result, the issue of price volatility has come to the forefront of public policy attention in recent years. [2]

This was especially the case within the European Union, where farmers have been gradually exposed to these global price fluctuations due to the increased market orientation of the reformed Common Agricultural Policy. In this context, European policy-makers are considering the need for specific risk management instruments in order to tackle price volatility and/or enable farmers to deal with its negative consequences. [3]

While there are several possible tools to achieve this, such as insurances and specialised financial instruments, prominent attention has recently been given to agricultural ‘futures’, which has risen from relative obscurity to become a buzz word and a topic of intense debate in agricultural decision-making circles. [4]

This report examines the effectiveness of futures in tackling and managing price volatility by firstly explaining how this instrument works in theory, before assessing its potential benefits and shortcomings, and finally giving an overview of the existing practices and regulations in the European Union.

- What are futures, and how do they work?

Futures contracts (or simply ‘futures’) are standardised, binding agreements in which a buyer and a seller agree to trade a specified quantity of an (agricultural) commodity at an agreed price on a given future date.

There are always five standardised elements in these contracts:

1. The type of commodity (for example wheat, corn, meat…)

2. The quantity of the commodity (the number of bushels of grain, pounds of livestock…)

3. The quality of the commodity (using specific grades)

4. The delivery point (the location at which the product should be delivered)

5. The delivery date (the day at which the product should be delivered; there are typically no more than four or five delivery dates per year) [5]

These standards are determined by futures exchanges (or futures markets), which are the public marketplaces where people can buy or sell futures contracts. This differentiates futures from forward contracts, which are private bilateral agreements (‘over-the-counter’) between two parties who can freely decide on the terms of the contract themselves. [6]

These futures markets add a time dimension to the physical market (or ‘spot market’) for agricultural products. Nevertheless, a key difference with the physical market is that the contract is traded on futures exchanges, and not the actual product itself. Therefore, futures are derivatives, as the value of the contract is derived from the underlying (agricultural) commodity. [7]

The price of the futures contract is determined through an auction process at the futures exchange, based on the balance between demand and supply for these contracts. Because these futures contracts are continuously traded on the futures exchanges, they pass through many hands, and in the end the contract will have a different buyer (‘short position’) and seller (‘long position’) than the original ones. [8]

The courses of these contracts are monitored on a daily basis, and buyers and sellers pay or receive margins on their future contracts, which are executed by a brokerage firm. [9] When the price of the futures drops, the broker will compensate for this price change by withdrawing the corresponding amount of money from the buyers’ margin account and depositing this amount on the sellers’ margin account. Similarly, when the price of the futures contract rises, the gains will be deposited to the account of the buyer and the seller will lose this money on his account. When the buyer or seller is required to deposit more money on his account to cover the losses on his futures contract, this is known as a margin call. [10]

In theory, the price of the futures contract and the price in the physical market (‘spot price’) should converge when the delivery date of the contract is approaching. This occurs through arbitrage: if there is a difference between the price on the futures market and the spot price of the commodities on the cash market, traders will buy and sell in these markets to profit from these differences, which will lead to a convergence in both prices. [11]

On the agreed delivery date (‘at maturity’), the contract expires and needs to be ‘settled’ in two possible ways: by actually delivering the goods or through a form of cash settlement. It is estimated that less than 2% of the futures contracts are eventually settled through physical delivery, in which the seller actually delivers the agreed amount of goods to the seller. In the large majority of the contracts, the seller simply offsets the contract by buying another futures contract, and receives or pays an amount of money for the expired futures contract (this is often done even before the date of expiration). Because the seller buys back the same amount of futures, his selling position is cancelled out and only the price will vary. [12]

Nevertheless, the commitment to deliver the physical commodity remains crucial, as it guarantees that the price of the futures contract will converge towards the ‘real’ price of the commodity (spot price) when the end of the contract approaches. For this reason, the delivery points, i.e. the locations where the products need to be delivered when the futures contract expires, also play a key role. The distance between the physical market and the delivery points of the futures market can require significant transportation and storage costs, and will thus largely dictate the affordability of futures for farmers. Because of these costs, there can be a structural gap between the futures price and the spot price, which is called the base. [13]

In general, the quality and success of a futures market is determined by its liquidity, or the frequency at which contracts are traded and the ease at which they can be exchanged. When liquidity is low, there are not enough market participants, it is difficult to exchange futures contracts and neutralise trading positions, and the price of the futures contracts do not reflect the actual price of the underlying product. [14]

The proper functioning of futures markets thus requires a sufficient number of actors, both hedgers who want to protect themselves against price changes and speculators who want to bet on these price changes, as this should guarantee that the prices of futures are a good reflection of the ‘real’ prices of the (agricultural) commodities. [15] On the other hand, if the futures market is illiquid, a small number of actors will be able to manipulate the prices of futures and the use of futures markets will become unattractive. [16]

- How can futures be helpful for farmers?

Futures markets perform two key functions which can be helpful for farmers: risk management and price discovery.

In the first place, futures are a risk management tool. Futures contracts give farmers the possibility to ‘lock in’ a certain harvest price for (a part of) their agricultural production, thus excluding the possibility that their selling price will fall in the future. [17] This method is commonly referred to as ‘hedging’. As a result, farmers do not have to cope with price volatility for these commodities anymore, as the risk of price changes is transferred from the farmers to speculators, who are willing to accept this risk in the hopes of making a profit out of it. [18] [19]

Secondly, futures can also be valuable as an instrument for price discovery. As futures markets reflect the price expectations of both buyers and sellers, they allow farmers to estimate the future spot prices for their agricultural products. In the context of unstable agricultural markets, being able to estimate the selling price at the beginning of the production process is especially valuable for farmers. [20]

These hedging and price discovery functions thus enable farmers to fix their prices for the future, reduce their risks, and better plan their production and investment decisions. [21]

- An example of how futures contracts work

Imagine a wheat producer has planted a crop in his field in May, when the price on the physical market (‘spot price) for wheat is €4 per bushel. However, the farmer will only be able to harvest and sell this wheat in September, and is not certain which price he will receive for his products at that moment. If the price of wheat rises between May and September, he will have higher earnings, while he will have less profits if the price drops in the coming months.

In order to protect himself against the possibility of a price drop, he can secure the current selling price by selling a number of bushels of wheat in the futures market in May, and buying a futures contract with the same number of bushels back in September, when he will sell his crops on the physical market. This will enable him to plan his investments over a longer term and limit potential losses. [22]

Meanwhile, a bakery may also try to secure a fixed buying price for wheat in order to determine its future production and profits. Therefore, the farmer and the bakery may enter into a futures contract, in which the farmer agrees to deliver 5 000 bushels of wheat to the bakery in September at a price of €4 per bushel. The value of this futures contract will be 20 000 euro (5000 bushels x €4).

In this scenario, the farmer holds the short position (agreeing to sell) while the bakery holds the long position (agreeing to buy). In practice, they can sell their positions for this contract on the futures market at any time, but for reasons of simplicity, we assume in this example that they keep their contract until the expiration date.

By entering into a futures contract, the farmer will receive the price mentioned in the futures contract in September, as any losses on the physical market will be compensated by a gain on the futures market. For instance, let’s assume that when the farmer buys the futures contract in May, the spot and future prices are identical at €4 per bushel of wheat. Because the futures market is assumed to function perfectly, these two prices should also continue to change in the same way.

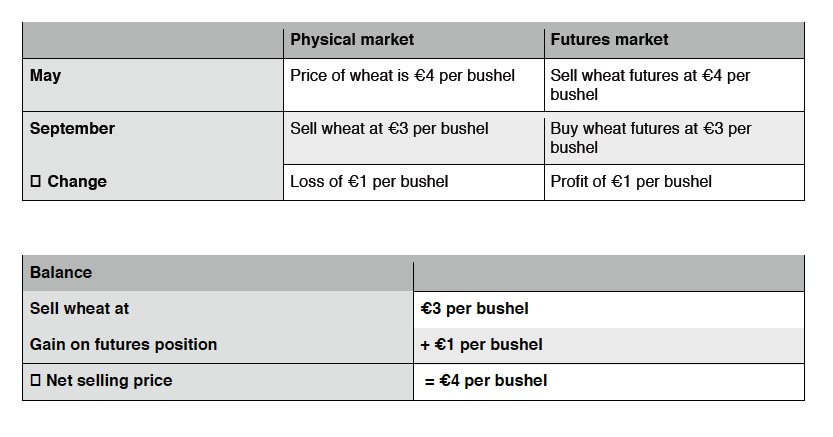

If in September, the price of wheat has dropped by €1 to €3 per bushel, the farmer will make a loss of €1 per bushel on the sale of his wheat on the cash market. However, the value of his futures contract is now €1 per bushel higher than other futures contracts (€4 compared to €3). Therefore, if he sells his futures contract of €4 per bushel and buys another futures at €3 per bushel, he makes a profit of €1 per bushel. Because the profits on his future position equal his losses on the physical market, his net selling price will still be €4 per bushel. [23] (See Example 1)

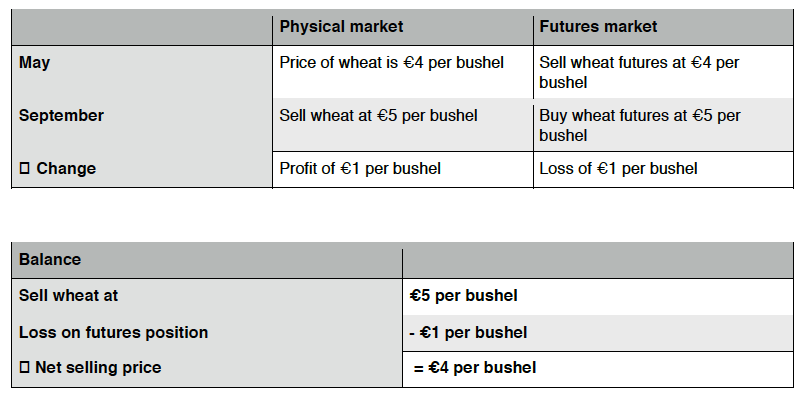

Likewise, if the price of wheat rises by €1 to €5 per bushel, the net selling price that the farmer receives would still be €4 per bushel, as the additional €1 per bushel he receives for selling his crops on the physical market are offset by the loss of €1 per bushel on the futures contract. (See Table 2)

Notice that in both examples, the gains and losses on the two markets cancel each other out, and the ‘locked in’ price target is achieved: a selling price of €4 per bushel of wheat in September. [24]

Before the expiration date, buyers and sellers are also required to have funds on a brokerage account to cover day-to-day gains or losses on their futures contract. Since the market rates for futures contracts change constantly, the margins are settled on a daily basis. These daily gains and losses from the trade in futures are immediately added to or subtracted from the buyers’ and sellers’ accounts by their broker.

For instance, let’s suppose that the price of futures contracts for wheat increases to €5 per bushel the day after the farmer and the bakery agreed on a futures contract of €4 per bushel. In this case, the farmer loses €1 per bushel, because the futures price is now higher than the future price at which he agreed to sell his wheat. The bakery, on the other hand, has made a profit of €1 per bushel, since he has to pay less than the rest of the market for the futures contract.

On the day of this price change, the farmer will therefore ‘lose’ €5 000 (€1 per bushel x 5 000 bushels) on his account, while the bakery’s account will gain €5 000 (€1 per bushel x 5 000 bushels). Nevertheless, it should be stressed that even if the farmer is making losses on his futures contract, it is likely that he is making gains on the ‘real’ price of his products, which is also expected to be €5 per bushel instead of €4.

This example shows that a futures contract is more a financial position than an actual trade agreement between two parties. For this reason, the farmer and bakery can also sell their positions to two speculators. If we apply the scenario of the daily price change mentioned above, the short speculator (‘seller’) would have lost €5 000 on his account, while the long speculator (‘buyer’) would have gained €5 000.

- Risks and shortcomings

4.1 Costs related to the use of futures

Farmers who engage in futures contracts are unfortunately also confronted with a variety of costs. First of all, buyers and sellers of futures are required to act through a brokerage firm to conclude their transactions, and these firms receive commissions and fees for conducting these services. Additionally, farmers have to pay in order to open an account with their broker, and are required to pay margins if their futures contracts experience negative price developments. These margins typically represent between 5% and 10% of the value of the underlying commodity. [25]

Secondly, futures are a complex risk management tool which requires a significant amount of technical know-how of the markets and regular information on daily price changes. However, individual farmers are often not aware of how this instruments functions in practice, and can therefore sometimes make limited use of it. Although they may hire advisors or advisory bodies who can help them with the use of futures by offering training and/or personalised monitoring of their transactions, this represents a considerable investment for farmers in terms of time and money. [26]

Thirdly, while a futures contract may be able to reduce the risk of falling prices for their products, a base risk will always remain: it is possible that the futures price will diverge from the price on the commodity markets, resulting in a lower price for the farmers than the one agreed on in the futures contract. This is a likely outcome if the futures market is not functioning well due to low levels of liquidity. [27]

Overall, it is estimated that these various costs cause the price that farmers receive to vary between 75 and 80% of the actual futures price. As a result, these costs can limit the accessibility and profitability of futures markets for the agricultural sector. [28]

4.2 Excessive speculation on futures can increase prices and price volatility

As outlined above, futures can be an effective instrument to manage price volatility if their exchanges are functioning properly, since they allow producers to hedge against the price risks on their products. However, it needs to be emphasised that this instrument does not reduce price volatility as such. [29]

On the contrary, price volatility is necessary for futures markets to be an effective instrument. If price variations did not occur or were only very limited, futures exchanges would not be attractive for speculators who are searching to make a profit out of these fluctuations, and this would cause futures markets to become illiquid and malfunctioning. [30]

Moreover, speculation on futures can even lead to sudden price rises, and more generally to higher levels of price volatility. Indeed, there is evidence that speculation on futures markets can artificially increase the demand for agricultural products, and thus lead to higher prices on the physical markets. In particular, financial speculation on commodity exchanges is seen as one of the main causes for the food price peaks in 2007-2008 and 2010-2011. [31]

In both of these periods, the short-term fluctuations in food prices were too sharp to have been the result of changes in the supply and demand factors for these products. For example, in 2008 wheat prices increased by 46% between January and February, fell back almost completely by May, rose again by more than 20% in June and fell back again from August onwards. Likewise, the price of rice rose by a staggering 165% between April 2007 and April 2008. The magnitude of these price fluctuations is so high that it is likely that they were largely driven by speculation, rather than being the result merely of market factors. [32]

Only speculators are able to make gains out of these extreme levels of price volatility, while they are detrimental for both producers and consumers. Even short-term price increases are unlikely to benefit agricultural producers, because they give misleading signals and wrong information which guide future production decisions. They can also threaten the income of farmers engaging in futures, as their contracts are likely to suffer from substantial costs and losses during price peaks. [33]

- Agricultural futures in the European Union

5.1 European futures markets for agricultural commodities

Traditionally, European agricultural markets were highly protected through the guaranteed price system of the original Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Given that public interventions limited the impact of downward price fluctuations on their incomes, futures contracts were initially not considered as necessary for farmers. [34]

However, the subsequent CAP reforms towards a reduction of market support gradually exposed the European agricultural sector to price variations. Faced with price volatility, farmers became increasingly interested in derivative markets for agricultural products. [35] As a result, a number of futures exchanges were developed in Europe, and futures contracts can now be traded for a variety of agricultural products. [36] [37]

The main European futures exchanges for agricultural commodities are situated in London and Paris. The Intercontinental Exchange Futures Europe (ICE Futures Europe) in London offers futures for wheat, barley, canola, coffee, cocoa, cotton, sugar, and soybeans [38], while the Marché à Terme International de France (MATIF) in Paris trades contracts for wheat, corn, barley, rapeseed, potatoes, and sunflower seeds. [39] In Central and Eastern Europe, the most advanced and liquid exchange is the Budapest Commodity Exchange (BCE), which offers futures for wheat, corn, barley, rapeseed, and sunflower seeds. [40] There are also some smaller futures exchanges, such as the one for olive oil in Jaén (Spain) and the Warsaw Commodities Exchange for wheat (Poland). [41] Moreover, there are plans to create futures markets for other commodities, such as dairy products. [42]

In the past, there have also been a limited number of futures exchanges in which contracts for animal products were traded, in particular for pork. An early example was the Commodity Exchange (‘Warenterminbörse’) in Hanover, which was created in 1998 and had a significant trading volume in the early 2000s, but was closed due to insolvency in 2008. Likewise, contracts on live pigs and piglets were created in Amsterdam in 1980 and 1991, yet these markets disappeared in 2003. [43] A major problem for these exchanges was the lack of market participants: only producers were positioning themselves, while there was limited interest from buyers (slaughterhouses, processors, manufacturers…). [44]

In general, the number of futures contracts traded on European exchanges and the use of futures by farmers has increased steadily in recent years. Nevertheless, the number of trading activities is still significantly lower than in the United States, even for commodities which are largely produced and consumed inside the European Union. European farmers also make less use of commodity futures: it is estimated that between 3% and 10% of them have used this risk management tool, compared to 33% in the United States. [45]

This remarkable difference can be explained by the fact that the US agricultural policy has traditionally focused more on a free market approach, which led American farmers to search for risk management instruments such as futures a lot earlier than their European counterparts. [46] Other reasons for the limited development of futures markets by European farmers include a lack of information and knowledge on futures, the bad image of the instrument due to its association with speculation, and the various costs related to the use of futures (see Chapter 5). [47]

5.2 The suitability of different agricultural sectors for futures

The experience of futures markets in Europe also revealed that not every agricultural commodity is equally suitable for a futures based approach. Because of the nature of futures contracts, it is necessary that the underlying products can be standardised, and not every agricultural sector has the same possibilities to do this.

Futures contracts are considered to be a very appropriate instrument for crops, and grains and oilseeds in particular, since it is relatively straightforward to standardise plant products. This is due to the fact that commodities such as wheat, corn, soybeans, and rapeseed are easy to store and deliver, which also reduces the risk that the quality of the product will fall short of the standards required in the futures contract. The standardisation process is even easier for feed grains, which are seen as the most appropriate commodities for futures contracts. [48]

As a result, ICE Futures Europe in London and MATIF in Paris offer good hedging opportunities for grains, as these markets have a high level of liquidity, have transparent prices which are accepted as European benchmarks, and farmers can easily access these markets through grain merchants or cooperatives. Moreover, efforts have been made to expand these futures markets, as ICE Futures Europe recently added a second delivery point for wheat in Dunkirk to the traditional delivery point in Rouen. [49]

Other plant products also have well-functioning European futures markets. For instance, ICE Futures Europe has a liquid exchange for refined white sugar and all types of cocoa and provides reliable price benchmarks for these products. These markets are liquid because both of these products can be stored for a relatively long period, which enables smooth exchanges and higher trading volumes. [50] Nevertheless, certain crops also suffer from very poor liquidity levels on their European futures markets due to limited trading volumes, such as barley and potatoes. [51]

On the other hand, creating standardised contracts poses more difficulties for animal products, due to their specialised nature, differences in species and quality, and the perishability of these products which complicates their storage. As mentioned in the previous section, there are no longer any European futures markets for pigs, as they suffered from very poor liquidity. Futures are also not available for beef products, as the production of multiple breads of beef makes it difficult to standardise these products. The trade volumes for lamb products are also deemed to be insufficient to create a well-functioning futures market. [52]

Likewise, dairy products are so perishable that they require complex storing procedures, which leads to illiquid futures markets with prices unrepresentative of the physical market. In particular, a futures market for milk is likely to have limited liquidity as it is highly vulnerable for spoiling. However, this does not apply to milk powder, which is easier to store and is thus more suitable for futures trading. [53]

In short, the degree to which agricultural products can be standardised is a major determinant for the liquidity, and therefore the success, of their futures exchange markets. Crops, and especially grains and oilseeds, are particularly suitable for a futures approach, while this risk management instrument may have little value for the meat and dairy sectors.

- An overview of EU legislation on commodity derivatives

Because of the increase in the trade of (agricultural) commodity contracts and the risks associated with speculation, policy-makers have paid growing attention to the regulation of their derivatives markets. Following the financial crisis of 2008, which was largely caused by problems with these derivatives, the European Union has introduced a variety of legislations to reform and strengthen the European financial markets.

In 2010, a series of reforms were proposed by Michel Barnier, the Commissioner for the Internal Market and Services from 2009 to 2014. This ‘Barnier package’ included the first pieces of EU-legislation regulating the functioning of commodity derivatives markets and the financial actors involved in these markets. [54] This chapter will present a brief overview of these regulations and will explicitly focus on the provisions relevant to futures markets and the aspects related to farming.

6.1 Legislation ensuring the proper functioning of derivatives markets

6.1.1 The MiFID Directive and MiFIR Regulation on markets in financial instruments

The Directive 2014/65/EU on ‘markets in financial instruments’ (MiFID) entered into force in July 2014, but will only be fully applied by January 2018 due to the complexity of its technical implementation details. [55] The MiFID Directive covers three main elements: position limits, trading venues, and speculative trading.

By establishing position limits, MiFID prevents market participants from holding more than a certain number of commodity derivative contracts at the same time. The specific numbers are determined by the national competent authorities and should be in accordance with the rules of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA).

However, these position limits are not applicable if derivatives are traded to hedge against price risks. In practice, this means that financial entities (such as pension funds) have to comply with these limits, while other participants (such as farmers) are normally exempted from this measure. The aim of position limits is to allow prices and settlements to function properly and therefore ensure convergence in the prices for derivatives and commodities. [56]

MiFID also stipulates rules for the trading venues in which commodity derivatives are exchanged, in terms of operational requirements, clearing and settlement services, access to trading, and transparency. Among others, the operators of these venues should be able to distinguish if a trade is performed for reasons of hedging or for speculative purposes, and should publish a weekly report with trading information for their commodity derivatives.[57]

Moreover, the Directive determines the operation conditions for investors, speculators, and speculating entities (banks, investment firms, and hedge funds), in order to avoid disruptive behaviour, manipulation and unfair trade practices. For instance, in order to avoid abusive trading, high frequency trading on extremely small price changes is not allowed. [58]

The MiFID Directive is complemented by Regulation No 600/2014 on ‘markets in financial instruments’ (MiFIR), which entered into force in July 2014 and should also be fully applied by January 2018. MiFIR further regulates trading venues by stipulating that all commodity derivatives traded on exchanges and other regulated markets must be cleared in a non-discriminatory way. Additionally, it requires trading venues and investment firms to continuously publish information on their trading in order enhance the transparency of the market. The MiFIR Regulation also covers commodity derivatives, and includes a definition of agricultural commodity derivatives which includes 20 categories of agricultural products.[59]

6.1.2 The MAR Regulation and CSMAD Directive on market abuse

Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 on ‘market abuse’ (MAR) and Directive 2014/57/EU on ‘criminal sanctions for market abuse’ (CSMAD) are pieces of legislation against market abuse for derivatives and physical commodities. They entered into force in July 2014, but will only be fully applicable in July 2016. [60] [61]

The MAR and CSMAD legislations originates from a review of the 2003 Market Abuse Directive and its related laws. Their aim is to ensure that all financial markets in the EU apply the same rules for market abuse, which involves ‘insider dealing, unlawful disclosure of inside information, and market manipulation’.

Abuse of inside information occurs if precise information is kept private while it is reasonably expected or legally required to be made public, and if this can have a significant impact on the prices of derivatives or commodities.

Market manipulation in agricultural commodity markets or their derivatives markets is also forbidden: it is not allowed to give false signals about supply, demand or prices; to secure a dominant position on the supply of demand; or to charge an abnormal price for commodities and derivatives. Specific measures includes the prohibition of abusive strategies for algorithm traders strategies and the manipulation of benchmarks for agricultural commodity indexes. [62]

The CSMAD lists the sanctions for these abuses, which are applied by the national competent authorities (in cooperation with ESMA and the financial markets) and can be as high as €5 million and 4 years of imprisonment. [63]

6.2 Legislation covering specific market participants

6.2.1 The AIFMD and UCTIS IV Directives on investment funds

The Directive 2011/61/EU on ’Alternative Investment Fund Managers’ (AIFMD) came into force in July 2011 and was fully implemented in July 2015. The AIFMD legislates the authorisation, operation and behaviour of investment funds (AIFs) and their managers (AIFMs). These investments funds involve hedge funds (including those who trade in commodity derivatives) and private equity funds. [64] [65]

The AIMFD is complemented by the Directive 2014/91/EU on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions related to ‘undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities’ (UCITS V), which entered into force in September 2014. [66] In practice, a UCITS is also an investment fund, and mostly an exchange traded fund (ETF) or commodity index fund. Among others, UCITS V stipulates that these investment funds cannot buy commodity derivatives with the capital of their investors. They should also be able to fulfil certain risk management requirements and monitor the risks on their positions. [67]

6.2.2 The CRR Regulation and CRD IV Directive on credit institutions and investment firms

The Regulation No 575/2013 on ‘prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms’ (CRR) and the Directive 2013/36/EU on ‘access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms’ (CRD IV) were applied in the EU member states from 2014 onwards. However, some provisions of the new banking rules have long transition periods and will only enter into force by 2019. [68]

In general, CRR and CRD IV constitute the legal framework for the authorisation, supervision and rules for credit institutions (banks) and investment firms. Specifically, they regulate how much capital these institutions must hold and which risk management system they must use. These rules cover activities for several derivatives, including futures for (agricultural) commodities. [69]

6.3 Relevance of the legislations for futures markets and agricultural products

The legislations of the ‘Barnier package’ could have some positive consequences for farmers engaging in futures contracts, as some of their general provisions are also applicable to futures markets.

By regulating the behaviour of speculators and restricting speculation through position limits, the MiFID Directive can improve the orderly functioning of futures exchanges and can help to ensure that futures are priced correctly. Together with the MiFIR Regulation, it also regulates the trading venues in which futures are exchanged. By laying down the rules and criminal sanctions for market abuse, the MAR Regulation and CSMAD Directive aim at preventing market manipulation on both the futures and physical markets for agricultural commodities.

Additionally, there are measures targeting specific financial actors who are active on futures exchanges. The AIFMD and UCTIS IV Directives prevent the various investment funds (hedge funds, private equity funds, exchange traded funds, and commodity index funds) from using investors’ money to deal in agricultural commodity futures. Meanwhile, the CRR Regulation and CRD IV Directive cover credit institutions and investment firms, and determine the risk management system they must adapt for trading in commodity futures.

However, the provisions in these EU laws apply mainly to general aspects of futures markets, while specific measures dealing with agricultural commodity futures remain very limited. [70] This lack of focus on agriculture can be explained by the fact that the legislation was largely influenced by the financial sector and other commodity producers, while the agricultural sector has hardly been involved in the decision-making process. [71] As the perspectives of EU farmers interested in hedging have not been taken into consideration, only a few of these new provisions protect their particular interests. [72]

Moreover, this complex legislative framework for commodity derivatives will only be fully implemented by January 2018, as important details still need to be settled through technical standards, delegated and implementing acts, and guidelines by the ESMA. The effectiveness of the current legislative framework will thus largely be determined by the implementation decisions on the European and national levels. [73] Due to the unfinished natures of the financial reforms, it cannot be guaranteed that European agricultural futures are already sufficiently protected against excessive speculation and market abuse. [74]

- Conclusion

The overview in this article reveals that futures remain a double-edged sword for the agricultural sector. If their exchanges are functioning properly, futures can enable farmers to secure a certain selling price for their products and estimate these prices at the beginning of their production process. This instrument can thus allow them to deal with price volatility risks and better plan their early production and investment decisions.

However, the use of futures also has several compelling disadvantages. The very nature of this instruments prevents farmers from benefitting from positive price developments for their products, as these prices are fixed by the futures contract. Engaging in futures contracts is also a rather expensive undertaking for farmers, as they need to pay commissions and fees to brokerage firms and advisors to manage these complex financial products on their behalf. Moreover, if the futures market are not functioning adequately, it is likely that the futures price will be different to the price on the physical markets, leading farmers to receive a lower price than the one agreed in the futures contract.

Most importantly, futures do not reduce price volatility for agricultural products as such, since fluctuations in prices are a necessary condition for the proper functioning of their exchanges. On the contrary, excessive speculation on futures can lead to artificial short-term price increases and thus even higher levels of price volatility, which is detrimental to both producers and consumers of agricultural products. In short, futures are not an instrument that can reduce price volatility, but remain at best a useful financial tool to manage its negative consequences.

The access for farmers in the European Union to this risk management tool has increased steadily in recent years, in line with the subsequent CAP reforms aiming at a more market-oriented European agricultural sector. A number of futures exchanges have been created and contracts can now be traded for a variety of agricultural products, particularly on the ICE Futures Europe in London and the MATIF in Paris.

Nevertheless, the trading volumes and the number of farmers using futures in Europe remain far more limited than those in the United States. The recent experiences of European futures markets also show that a futures approach is not equally suitable for all agricultural sectors. Exchanges for crops and oilseeds are widely available and rather successful, as these products are relatively easy to standardise and store, while the perishability of meat and dairy puts structural limits on the development of their futures markets.

Because of this growth in the trade of commodity contracts and their problematic role in the economic crisis starting in 2008, the European Union has introduced a number of legislations to better regulate these financial markets. While this ‘Barnier package’ could lead to the better protection of farmers engaging in futures, it only includes very limited specific measures on agricultural commodity futures and is thus not fully adapted to the specific needs of the agricultural sector. Moreover, as some important technical details still have to be settled, this complex legislative framework will only be fully applicable in 2018, which means that farmers are not yet sufficiently protected against excessive speculation and market abuse on agricultural futures markets.

References

Adenacioglu, H. ‘The Futures Market in Agricultural Products and an Evaluation of the Attitude of Farmers: A Case Study of Cotton Producers in Aydin Province in Turkey’, New Medit, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2011, pp. 58-64.

Budapest Stock Exchange, https://bse.hu/newkibdata/120577480/hat160127.pdf.

CEPS, Price Formation in Commodities Markets: Financialisation and Beyond, 2013.

CME Group, Self-Study Guide to Hedging with Grain and Oilseed Futures and Options, 2015.

De Schutter, O. ‘Food Commodities Speculation and Food Price Crises’, Briefing Note, Vol. 2, 2010, pp. 1-14.

Dismukes, R. Bird, J. and Linse, F. ‘Risk Management Tools in Europe: Agricultural Insurance, Futures, and Options’, US and EU Food Comparisons, 2004, pp. 28-32.

European Commission, ‘Agricultural commodity derivative markets: the way ahead’, Commission Staff Working Document, 2009, pp. 1-26.

European Commission, Alternative Investments, http://ec.europa.eu/finance/investment/alternative_investments/index_en.htm.

European Commission, Commission extends by one year the application date for the MiFID II package, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-265_en.htm?locale=en.

European Commission, Proposals for a Regulation on Market Abuse and for a Directive on Criminal Sanctions for Market Abuse, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-11-715_fr.htm?locale=EN.

European Commission, UCITS – Undertakings for the collective investment in transferable securities, http://ec.europa.eu/finance/investment/ucits-directive/index_en.htm.

European Parliament, Financial Instruments and Legal Frameworks of Derivatives Markets in EU Agriculture: Current State of Play and Future Perspectives, 2014.

Ghosh, J. ‘Commodity Speculation and the Food Crisis’, Excessive Speculation in Agricultural Commodities, 2011, pp. 51-56.

Glauben T., Prehn, S., Dannemann, T., Brümmer, B., and Loy, J. ‘Options trading in agricultural futures markets: A reasonable instrument of risk hedging, or a driver of agricultural price volatility?’, IAMO Discussion Papers, 2014, pp. 1-3.

ICE, Products – Futures and Options, https://www.theice.com/products/Futures-Options/Agriculture.

Kolb, R. and Overdahl, J. Financial Derivatives: Pricing and Risk Management, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Loy, J. Relative Forecasting and Hedging Efficiency of Agricultural Futures Markets in the European Union: Evidence for Slaughter Hog Contracts, 2002.

OECD, Managing Risk in Agricultural Policy Assessment and Design, 2011.

MATIF, Commodity Factsheet, http://www.csidata.com/factsheets.php?type=commodity&format=html&exchangeid=91.

Ministry of Agriculture and Trade of the Czech Republic, Information about European Commodity Exchanges, http://www.mpo.cz/zprava120086.html.

Norton Rose Fulbright, Key things you should know: MAR/CSMAD, http://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/knowledge/publications/117959/key-things-you-should-know-mar-csmad.

Pennings, J. and Egelkraut, T. ‘Research in Agricultural Futures Markets: Integrating the Finance and Marketing Approach’, German Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 52, No. 6, 2003, pp. 300-308.

Prehn, S., Glauben, T., Loy, J., Pies, I., and Matthias, G. ‘The impact of long-only index funds on price discovery and market performance in agricultural futures markets’, IAMO Discussion Papers, 2014, pp. 1-21.

Roussillon-Montfort, M. ‘Les marchés à terme agricoles en Europe et en France’, Notes et Études Économiques, No. 30, 2008, pp. 99-124.

Report on the High Level Group on Milk, 2010.

Tangermann, S. ‘Risk Management in Agriculture and the Future of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy’, ICTDS Issue Paper, No. 34, 2011, pp. 1-41.

[1] M. Roussillon-Montfort, ‘Les marchés à terme agricoles en Europe et en France’, Notes et Études Économiques, No. 30, 2008, p. 101.

[2] European Parliament, Financial Instruments and Legal Frameworks of Derivatives Markets in EU Agriculture: Current State of Play and Future Perspectives, 2014, p. 20.

[3] R. Dismukes, J. Bird and F. Linse, ‘Risk Management Tools in Europe: Agricultural Insurance, Futures, and Options’, US and EU Food Comparisons, 2004, p. 28.

[4] H. Adenacioglu, ‘The Futures Market in Agricultural Products and an Evaluation of the Attitude of Farmers: A Case Study of Cotton Producers in Aydin Province in Turkey’, New Medit, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2011, p. 58.

[5] CEPS, Price Formation in Commodities Markets: Financialisation and Beyond, 2013, p. 30.

[6] European Commission, ‘Agricultural commodity derivative markets: the way ahead’, Commission Staff Working Document, 2009, p. 23.

[7] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 104.

[8] European Commission, op.cit., p. 23.

[9] R. Kolb and J. Overdahl, Financial Derivatives: Pricing and Risk Management, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, 2009, p. 126.

[10] CME Group, Self-Study Guide to Hedging with Grain and Oilseed Futures and Options, 2015, p. 6.

[11] European Parliament, op.cit., pp. 22-23.

[12] CEPS, op.cit., p. 32.

[13] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., pp. 106-107.

[14] Ibid., p. 104.

[15] J. Pennings and T. Egelkraut, ‘Research in Agricultural Futures Markets: Integrating the Finance and Marketing Approach’, German Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 52, No. 6, 2003, p. 304.

[16] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 104.

[17] S. Prehn et al., ‘The impact of long-only index funds on price discovery and market performance in agricultural futures markets’, IAMO Discussion Papers, 2014, p. 7.

[18] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 19.

[19] T. Glauben, ‘Options trading in agricultural futures markets: A reasonable instrument of risk hedging, or a driver of agricultural price volatility?’, IAMO Discussion Papers, 2014, pp. 1-2.

[20] CEPS, op.cit., p. 30.

[21] J. Loy, Relative Forecasting and Hedging Efficiency of Agricultural Futures Markets in the European Union: Evidence for Slaughter Hog Contracts, 2002, p. 5.

[22] CEPS, loc.cit.

[23] CME Group, op.cit., p. 9.

[24] Ibid., p. 10.

[25] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 114.

[26] Ibid., pp. 114-116.

[27] Ibid., p.116.

[28] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 24.

[29] Report of the High Level Group on Milk, 2010, p. 18.

[30] Ibid., p. 19.

[31] Prehn, op.cit., p. 17.

[32] O. De Schutter, ‘Food Commodities Speculation and Food Price Crises’, Briefing Note, Vol. 2, 2010, p. 3.

[33] J. Ghosh, ‘Commodity Speculation and the Food Crisis’, Excessive Speculation in Agricultural Commodities, 2011, p. 54.

[34] OECD, Managing Risk in Agricultural Policy Assessment and Design, 2011, p. 33.

[35] S.Tangermann, ‘Risk Management in Agriculture and the Future of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy’, ICTDS Issue Paper, No. 34, 2011, pp. 5-6.

[36] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 115.

[37] Dismukes, op.cit., p. 29.

[38] ICE, Products – Futures and Options, https://www.theice.com/products/Futures-Options/Agriculture.

[39] MATIF, Commodity Factsheet, http://www.csidata.com/factsheets.php?type=commodity&format=html&exchangeid=91.

[40] Budapest Stock Exchange, https://bse.hu/newkibdata/120577480/hat160127.pdf.

[41] Ministry of Agriculture and Trade of the Czech Republic, Information about European Commodity Exchanges, http://www.mpo.cz/zprava120086.html.

[42] European Commission, op.cit., p. 4.

[43] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 114.

[44] Ibid., p. 121.

[45] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 22.

[46] Dismukes, op.cit., p. 31.

[47] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 19.

[48] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 113.

[49] CEPS, op.cit., p. 191.

[50] Ibid., p. 246.

[51] Ibid., p. 261.

[52] Roussillon-Montfort, op.cit., p. 113.

[53] Report of the High Level Group on Milk, op.cit., p. 19.

[54] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 39.

[55] European Commission, Commission extends by one year the application date for the MiFID II package, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-265_en.htm?locale=en.

[56] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 45.

[57] Ibid., p. 46.

[58] Ibid., p. 47.

[59] Ibid., p. 48.

[60] European Commission, Proposals for a Regulation on Market Abuse and for a Directive on Criminal Sanctions for Market Abuse, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-11-715_fr.htm?locale=EN.

[61] Norton Rose Fulbright, Key things you should know: MAR/CSMAD, http://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/knowledge/publications/117959/key-things-you-should-know-mar-csmad.

[62] European Parliament, op.cit., p. 52.

[63] Ibid., p. 53.

[64] European Commission, Alternative Investments, http://ec.europa.eu/finance/investment/alternative_investments/index_en.htm.

[65] European Parliament, op.cit, pp. 53-54.

[66] European Commission, UCITS – Undertakings for the collective investment in transferable securities, http://ec.europa.eu/finance/investment/ucits-directive/index_en.htm.

[67] Ibid., pp. 56-57.

[68] Ibid., p. 54.

[69] Ibid., p. 55.

[70] Ibid., p. 67.

[71] Ibid., p. 89.

[72] Ibid., p. 14.

[73] Ibid., p. 88.

[74] Ibid., p. 69.