October marked the adoption of the Farm to Fork strategy as a shared European strategy, and not only a European Commission’s initiative. In fact, the vote of the European Parliament on the texted agreed by the joint ComEnvi & ComAgri Committees confirmed most of the Commission’s vision of the future of European agriculture and the […]

Our Works

How to tackle price and income volatility for farmers? An overview of international agricultural policies and instruments

(Executive summary available here in EN and FR)

-

Introduction

While the markets for agricultural commodities have an inherent tendency to be rather volatile, the price volatility of these products has been particularly high in the last decade. More specifically, sharp increases in global food prices in 2007-2008 and 2010-2011 were followed by recurring periods of often severe price depression. As these changes in prices were unpredictable, price volatility had a number of negative consequences in all parts of the world. [1]

The reason for this is that large variations in prices create a high level of uncertainty among producers and consumers. Producers are more concerned about the prospect of low prices, since a lower income may threaten their viability in the long term. Meanwhile, the ability of poor households to ensure their nutrition and other basic needs (such as education and health care) can be compromised when food prices are high. [2] Additionally, farmers are less willing to invest in productivity-raising assets when prices are unpredictable, and this may encourage them to take sub-optimal investment decisions in the long term. [3] [4]

As a result, the recent price fluctuations and their detrimental impact on the agricultural sector have stimulated a renewed debate on the issue of volatility and the possibilities of stabilising the agricultural markets. [5] Since the volatility in prices and incomes for farmers is likely to remain and even increase in the future, the possibilities to manage these risks should be a primary concern for both stakeholders and policy-makers. [6]

Against this background, this report focuses on the agricultural policies and instruments that can support farmers in the management of these types of volatility. After briefly outlining the causes of price and income volatility for farmers and the options to deal with this, the policy instruments of the main agricultural countries and regions will be assessed, namely those of the European Union, the United States, Brazil, China and Australia. In particular, special attention will be given to the state support for agricultural insurance schemes.

-

Causes of price and income volatility

Essentially, high levels of price and income volatility for farmers are related to the market fundamentals of supply and demand. However, they can be intensified by other macro-economic variables, the broad political and legislative environment for farmers, and speculation on agricultural products.

In the first place, variations in prices and incomes are the result of shifts in supply and demand. As food demand and supply have a low price elasticity in the short run, meaning that they are not very responsive to price changes, fluctuations in agricultural prices tend to be especially strong. On the one hand, the nature of food as a basic necessity means that it is, by definition, price inelastic. On the other hand, the supply of food cannot respond quickly to price changes, since it often takes a significant amount of time to produce agricultural products. As a result of this limited price responsiveness of demand and supply, unexpected changes in the amount of output often require large price changes to restore the market equilibrium, which causes agricultural markets to be rather volatile. [7]

Other macro-economic conditions can also be important drivers of price volatility. Some of the structural factors that can simultaneously influence the prices of different crops include exchange rates, energy and fertiliser prices, and interests rates. [8] Additionally, due to evolutions in agricultural policies and legislations, and especially under the impulse of the WTO agreements, agricultural markets have become more open and competitive in the last decades, leading to increased price volatility and variations in farm income. [9] Finally, as agricultural products can now also easily be sold as financial assets, they are exposed to shocks on related commodity markets (such as the energy and metal markets), and speculation on these products is deemed to be a major cause of increasing price changes.[10]

These endogenous risks, which are the result of the behaviour of market participants, are the main causes for the volatility in agricultural prices and incomes. However, farmers are also exposed to exogenous risks, which are independent from market conditions and are caused by weather and climatic factors.

Indeed, agricultural activities are especially sensitive for climatic factors, since these play an important role in the production process. Weather conditions can strongly affect the crop and livestock production and cause annual variations in yields, while extreme weather events can significantly damage agricultural output. Therefore, the production of agricultural commodities remains much more variable than the output of other industrial sectors. Moreover, as climate change may result in worsening production conditions for farmers, these exogenous shocks are expected to increase in the future. [11]

In short, large price fluctuations and the resulting variations in income, which are caused by the endogenous and exogenous factors described above, represent risks that are specific to farmers. However, the agricultural sector also faces multiple risks that affect other sectors as well, including business/entrepreneurial risks, legal risks, social risks, financial risks etc. [12] Nevertheless, price and income volatility are generally considered to be the most important elements of uncertainty for farmers. The remainder of this report will therefore focus on the instruments that are being used to tackle these issues.

-

Methods to deal with income and price volatility

Instruments to tackle the price and income volatility for farmers can involve private initiatives, public policy measures, or a mix of both.

First of all, there are several ways for farmers to tackle these issues themselves, as they can try to reduce the occurrence of these risks, mitigate their damage and/or cope with the impact of these risks on their income. For instance, by using the appropriate production technologies (e.g. by planting drought-resilient crop varieties or investing in irrigation methods), farmers can reduce the risks of yield losses due to weather conditions.

Risks related to fluctuating prices can also be mitigated through the use of several market-based options, such as future markets and insurances. However, these instruments are often rather costly in terms of fees and prices. Finally, the options for farmers to cope with risks mainly consist of financial approaches, such as saving money when their incomes are high and using these reserves when their revenues are low. [13]

Additionally, there are several other private protection instruments for farmers, including the diversification and rotation of crops, the membership of farmers in a cooperative, and the use of storages for their products.

Governments can also empower farmers by creating policy and legal frameworks that improve their ability to manage these risks. [14] Apart from enhancing the training of farmers and providing reliable information on market developments, public policies can maintain safety nets to help farmers to deal with income loss as a result of catastrophic events or major disturbances of the market.

Some public measures to achieve these outcomes include insurance schemes, the provision of disaster assistance, the enhancement of markets for derivatives, fiscal measures, contra-cyclical payments, mutual funds, storage support and improving the access to credit for farmers. The next chapter presents an overview of the public instruments that are used to tackle price and income volatility in the European Union, the United States, Brazil, China, and Australia. [15]

4. International agricultural policies and instruments to protect farmers against price and income volatility

a) The European Union

-

The evolution of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the EU consists of several policy instruments that help farmers to deal with price and income volatility. These instruments have evolved significantly over time.

When the CAP was established in the early 1960s, it aimed at ensuring a fair standard of living for farmers by maintaining high and stable prices for the major agricultural products, through both domestic (e.g. intervention buying) and border measures (e.g. export subsidies and variable levies on imports). These price support policies largely continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s, although some sector-specific adjustments were made to tackle some of its negative consequences, for instance through production quotas and voluntary set-asides. [16]

However, after the Uruguay round of the GATT negotiations, the traditional CAP policies became unsustainable and pressures to change this approach became too high. In 1992, the European Commissioner for Agriculture Ray MacSharry initiated the first major reform of the CAP by reducing the level of price intervention and import/export tariffs, and offering direc t coupled payments to farmers as a compensation. [17] Afterwards, the reforms implemented under the Commissioners Franz Fischler and Mariann Fischer Boel decoupled these payments from agricultural production, and the EU markets for agricultural products became more open to global influences and more

t coupled payments to farmers as a compensation. [17] Afterwards, the reforms implemented under the Commissioners Franz Fischler and Mariann Fischer Boel decoupled these payments from agricultural production, and the EU markets for agricultural products became more open to global influences and more

vulnerable to price swings. [18]

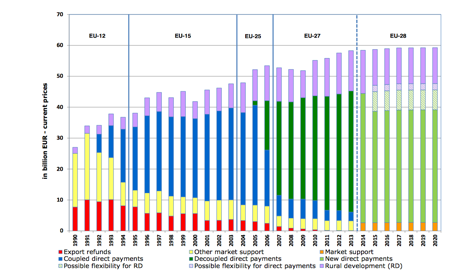

In short, through a series of reforms in the last two decades, the CAP has evolved towards the dismantling of price support for farmers and an increasing market orientation for agriculture, leaving more room for fluctuating prices as a result of changes in global supply and demand (see figure). [19] This transformation can be demonstrated by the evolution of the expenditure on the CAP: while market interventions still accounted for up to 90% of the total CAP budget in 1992, they represented only 5% in 2013. [20]

-

Instruments under the current Common Agricultural Policy (2014-2020)

The current CAP gives assistance to farmers through ‘Market support measures and direct subsidies’ (Pillar 1) and ‘Rural Development Programmes’ (Pillar 2). [21] The budget for the first pillar consists of 312,74 billion euros, while 95,58 billion euros is made available for the second pillar. Although member states can still decide to give some support to farmers coupled to production, market support measures now only account for a small share of the CAP budget. [22]

The most important changes that were introduced in the last CAP reform (for the period 2014-2020) were related to the system of fixed direct payments in Pillar 1, as the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) replaced the Single Payment Scheme (SPS). While these direct payments are not explicitly designed as an instrument to tackle price volatility, they help to shield European farmers from strong fluctuations in revenues. According to estimates of the European Commission, these ‘decoupled’ payments now account for nearly one third of the income of European farmers. As these continuous financial flows are not subject to market outcomes and unexpected changes, they provide these farmers with a significant degree of income stability. [23] [24]

The CAP for the period 2014-2020 also strengthened the risk management instruments that were introduced in 2009, but they have not been very successful so far. These instruments were transferred from the first to the second pillar, and as a result they have become optional measures which can be co-financed by the Member States. They consist of the three following tools:

– Financial support to farmers for the premiums on insurances for crops and livestock against losses caused by adverse climatic events and diseases

– Financial support for mutual funds to compensate farmers for production losses related to climatic and environmental events

– An Income Stabilisation Tool (IST), mobilising financial support for farmers who experience severe income losses (exceeding 30% of the average annual income) [25]

Firstly, the use of EU funds to finance the premiums on domestic insurance markets has so far been limited to eight countries (France, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, and the Netherlands) and four regions (Flanders, Continente, Madeiras, and Açores). Only 200 000 European farm holdings are now receiving this type of support for their premiums, and the large majority of them are based in France and Italy (see Table 1). The total expenditure for this instrument, of both the European Union and the national governments, currently reaches around 2.2 billion euros (see Table 2).

Table 1: Number of agricultural holdings supported by European risks management instruments

| Number of agricultural holdings | Premiums | Mutual Funds | IST | Total |

| BE – Flanders | 1.300,0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ES – Castilla y Leon | 0 | 0 | 950,0 | 950 |

| FR | 97.000,0 | 398.000,0 | 0 | 495.000 |

| HR | 8.300,0 | 0 | 0 | 8.300 |

| HU | 10.500,0 | 0 | 4.500,0 | 15.000 |

| IT | 80.000,0 | 5.000,0 | 5.000,0 | 90.000 |

| LT | 1.450,0 | 0 | 0 | 1.500 |

| LV | 4.000,0 | 0 | 0 | 4.000 |

| MT | 1.500,0 | 0 | 0 | 1.500 |

| NL | 1.300,0 | 0 | 0 | 1.300 |

| PT – Continente | 785,0 | 0 | 0 | 800 |

| PT – Madeira | 350,0 | 0 | 0 | 350 |

| PT – Açores | 150,0 | 0 | 0 | 150 |

| RO | 0 | 15.000,0 | 0 | 15.000 |

| Total | 206.635 | 418.000,0 | 10.450,0 | 633.850 |

Table 2: Total expenditure on European risks management instruments

| Total expenditure (EAFRD + national) | Premiums | Mutual Funds | IST |

| BE – Flanders | 5.000.000 | 0 | 0 |

| ES – Castilla y Leon | 0 | 0 | 14.000.000 |

| FR | 540.750.000 | 60.000.000 | 0 |

| HR | 56.600.000 | 0 | 0 |

| HU | 76.540.000 | 0 | 18.800.000 |

| IT | 1.396.800.000 | 97.000.000 | 97.000.000 |

| LT | 17.460.000 | 0 | 0 |

| LV | 10.000.000 | 0 | 0 |

| MT | 2.500.000 | 0 | 0 |

| NL | 54.000.000 | 0 | 0 |

| PT – Continente | 49.700.000 | 0 | 0 |

| PT – Madeira | 800.000 | 0 | 0 |

| PT – Açores | 2.350.000 | 0 | 0 |

| RO | 0 | 200.000.000 | 0 |

| Total | 2.212.500.000 | 357.000.000 | 129.800.000 |

Secondly, there is the possibility to receive financial support from the EU for mutual funds that compensate farmers for heavy production losses. These funds can be used to compensate for losses which are officially recognised by a competent national authority, or to provide subsidies which partly cover the costs of setting up the funds, the payments to farmers, and eventual interest rates on the loans undertaken by the funds. An index is used to calculate the production losses, and these should involve at least 30% of average past production in order to receive compensatory payments.

However, this proposal has not yet instigated much change in the member states, since creating new mutual funds is often very costly. As a result, it has only been used by France, Italy and Romania, where 418 000 agricultural holdings are benefiting from these funds. However, participation is mainly concentrated in France (representing almost 400 000 holdings), while a very limited number of farmers is affected in Italy and Romania (see Table 1). Total public spending on this measure accounts for 357 million euros (see Table 2). [26]

Thirdly, the Income Stabilisation Tool (IST) is a mutual fund to compensate farmers for severe income losses. This fund, which can be publicly subsidised, may provide support to agricultural producers when they experience an average income loss of 30% over a period of three years. In this sense, the provisions for these tool are similar to those for the mutual funds to compensate for production losses.

However, there has been a lack of details regarding the implementation of this instrument in practice. Therefore, only Italy, Hungary, and the Spanish region Castilla y León are now adopting this tool, covering a very limited number of 10 000 agricultural holdings and accounting for 130 million euro in total public support (see Table 1 and 2). [27]

In short, the three instruments described above are currently weak options for member states rather than full-fledged programmes for farmers to deal with income and price volatility. As the guidelines for designing these tools remain rather vague (especially for the mutual funds and the IST), these programmes are treated more as theoretical concepts than as real instruments, and their implementation through the actions of Member States has been very limited since 2009. Currently, only four regions and eight countries are using the instrument to support insurance premiums, while the mutual funds and IST are only implemented in three countries. The total amount of European financial support for these tools is limited to 1.7 billion euros. According to the Commission, these instruments should be fully implemented by the end of 2018, when the mid-term evaluation of the CAP takes place.[28]

Table 3: European Union expenditure on risk management instruments

| Expenditure of EAFRD | Premiums + Mutual Funds + IST |

| BE – Flanders | 3.142.949 |

| ES – Castilla y Leon | 7.420.000 |

| FR | 600.750.000 |

| HR | 48.172.367 |

| HU | 78.641.932 |

| IT | 715.860.000 |

| LT | 14.841.242 |

| LV | 6.800.000 |

| MT | 1.875.000 |

| NL | 14.690.000 |

| PT – Continente | 40.754.000 |

| PT – Madeira | 655.988 |

| PT – Açores | 2.000.000 |

| RO | 170.000.000 |

| Total | 1.705.603.478 |

-

National agricultural policies in the EU

In general, there are no fully developed national policies of EU Member States to protect farmers from price and income volatility. This might be explained by the fact that, for a long period of time, the agricultural policies of the CAP provided European farmers with a high degree of price and income stability. [29] However, farmers in all Member States have access to some form of insurance against the production risks caused by natural events, yet there are significant differences in the coverage and design of these insurance schemes. [30]

Crop insurances for single risks are well-developed and exist in all EU-countries. In around half of the EU-countries, single risk insurances are provided to farmers on a private basis. These countries include Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Other member states provide partial public support to these insurances in the form of subsidies, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Finally, in Cyprus there is a compulsory public single risk insurance, which is partially subsidised. In general, the most widely used type of this insurance is the one against hail damage. [31]

Combined insurances covering multiple risks are also provided in several member states. They are available and supported by the state in Austria, the Czech Republic, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain. In Bulgaria, Finland, France, Hungary, Slovenia, and Sweden, this type of insurance is only provided by private companies. Again, Cyprus has a compulsory and partially subsidised insurance scheme, while Greece created a hybrid public insurance system which is partly subsidised and partly compulsory.

In a few countries, farmers also have access to yield insurances, which cover yield losses for a given crop caused by all types of natural events. They are only developed in countries where significant public support is provided to agricultural insurance schemes, namely in Austria, France, Italy, Luxembourg, and Spain. [32]

Finally, revenue insurances have not been developed in Europe yet (they are only applied in the United States). This type of insurance combines yield and price insurances, and takes into account the agricultural production costs. Farmers are compensated if the value of their production falls below a certain (historical) level. [33]

If we look at the EU countries in more detail, it becomes clear that Spain has the most elaborate insurance system against natural risks. In essence, the Spanish and regional government partially cover the costs of the premium that farmers have to pay to private insurance companies (between 20% and 60%). Furthermore, the insurance support is based on institutional arrangements between both public and private actors, and farm unions are actively involved in the management of the system. [34]

This insurance system was created in 1978, and the number of insurable crops covered has been expanding consistently in the following decades. Insurance schemes now cover damage to agricultural production produced by natural conditions such as diseases, drought, fire, flood, frost, hail, rains, snow and wind. While some yield insurances are offered, combined insurances are the most common instrument to cover these risks for different agricultural sectors.

The degree of coverage of the Spanish agricultural insurances differs significantly across sectors and products, and is the broadest for crops such as cereals, fruits and olives. Spain is currently not using the EU funds to subsidise its insurance system. [35]

Other countries, such as France, Italy, Luxembourg and Austria, also have well-developed insurance schemes, and farmers can be covered for most types of risk. Farmers in these countries often have a basic coverage against hail and have access to an additional yield insurance. However, this does not mean that these types of insurance are widely used in these countries. For instance, the level of insurance coverage is rather low in Italy, despite the fact that national legislation promotes the use of these instruments. In general, these insurances are not very attractive for farmers due to their high premium costs. [36]

Both single and combined risk insurances are also available in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Sweden; yet they only cover hail damage and a few other risks. In Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, there is no public support for insurances at all. Single risk insurances are the main instrument to protect farmers in these countries, especially for hail damage, and there is a lack of coverage against other types of risks. Insurance systems are even less developed in some Northern European countries, such as the Baltic States. Finally, Cyprus manages their insurance schemes in a different way as the others, since farmers are obliged to subscribe for insurances provided by the government. [37]

Furthermore, these production risk insurances involve different ‘triggers’, meaning that a certain amount of losses has to occur before the insurance company makes compensatory payments to the farmers. The table below gives an overview of some of these trigger rates for the types of insurance in the EU member states. [38]

| Table 4: Trigger rates for agricultural insurance schemes | Single-risk insurance | Combined insurance | Yield insurance | Livestock |

| Austria | 8% for hail insurance | Depends on type of crop | Depends on type of crop | |

| Belgium | 5% for hail insurance | |||

| Bulgaria | 5% | 10, 30 or 40% | ||

| Cyprus | 15% (hail frost and wind), 20% (flood and heatwave), 35% (water), and 40% (drought) | |||

| Czech Republic | 8-10% | |||

| Finland | 5-20% | Variable | ||

| France | 15% on average | 15% on average | 15% on average | |

| Germany | Hail damage: 8% for arable crops and wine, 10% for fruits and vegetables | |||

| Greece | 15% for hail insurance | 20% (with exceptions) | 1-2% | |

| Hungary | 5% | 10% | ||

| Italy | 10-30% | 20% | ||

| Lithuania | 6-12% | 10-30% | ||

| Luxembourg | Hail insurance: 8% (arable crops) and 10% (fruits and vegetables) | 8% (flood, frost, storm) and 20-40 (drought) | ||

| Poland | 10% | 10% | 20% | |

| Romania | 10% | 10% | ||

| Slovenia | 5% | |||

| Spain | 10-30% | 10-35% | 10%

|

b) The United States

The United States is the largest exporter of agricultural commodities in the world and has a big domestic market for these products. The country shifted its agricultural policy away from the traditional price support schemes with the Farm Bills of 1985, 1990 and 1996, in order to fulfil the requirements of the WTO. To compensate farmers for these reduced market payments, there was a move towards direct payments with the 2002 and 2008 Farm Bills, which introduced the counter-cyclical payment programmes of the CCP and ACRE. As a result, fixed direct payments became the most important source of support for farmers from the 1990s until 2013. [39]

The current US agricultural policy (for the period 2014-2018) is described in the 2014 Farm Bill, which was approved around the same time as the last CAP reform. The most important change in this new programme was the elimination of all fixed direct payments, by repealing the Direct Payments (DP), the Countercyclical Payments (CCP), the Average Crop Revenue Election (ACRE) and the Supplemental Revenue Assistance Payments (SURE) programmes. [40]

Instead, two new risk-management programmes were established to supplement crop insurances and protect farmers when they suffer significant losses: a Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programme to address sharp declines in commodity prices and an Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) programme to cover a portion of a farmer’s revenue losses when crop prices fall to 86% of the ‘historical’ benchmark. Producers can only enrol in one of these two instruments, and subsidies are limited to a maximum of 125,000 dollars per person. The cost of the PLC programme was approximately 13.1 billion dollars in the financial year 2013, while the ARC programme costed 14.1 billion dollars.[41]

Additionally, a new dairy margin protection programme was created to compensate farmers when national milk prices drop too close to feed costs. The amount of indemnity payments given by the US government depends on the annual coverage decision made by the dairy farmer. [42] This new programme replaces the Milk Income Loss Contract programme and is likely to result in higher government support to help secure the income of American dairy farmers. [43] This contrasts with the situation in Europe, where the abolition of milk quota will lead to lower prices and a higher income risks for farmers in the short term. [44]

Crop insurance programmes are now the main policy tools used to support US Farmers. The 2014 Farm Bill maintains and strengthens the existing crop insurance programmes under the Common Crop Insurance Policy, and expands their scope to other products (organic products, bio-energy crops and speciality crops) and other elements such as livestock diseases, specific production practices, and business interruption.

Additionally, two new crop insurance programmes were created, the Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO) for the main crops and the Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) for cotton. Under these programmes, producers can receive additional insurances to cover a part of the losses which is not included by the traditional crop insurance policies (‘shallow losses’). Coverage under SCO is triggered only if the area loss exceeds 14%, and would cost 1.7 billion dollars over the next 10 years. Because cotton growers are not eligible for the new PLC and ARC risk mitigation programmes, the Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) was created for them. This programme enables cotton producers to obtain an area wide group-risk insurance as a supplementary insurance or a stand-alone policy.

The financial support for insurances against natural disasters was also extended, as the 2014 Farm Bill reauthorised and modified certain Supplemental Agricultural Disaster Assistance programmes. These programmes include the Livestock Indemnity Payments; the Livestock Forage Disaster Program; the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees and Farm-Raised Fish; and the Tree Assistance Program.

The total budget cost of the 2014 Farm Bill is estimated to be 489 billion dollars for the period 2014-2018, and almost 1000 billion dollars for the next ten years. [45]

In short, the US agricultural policy uses a very different set of tools and instruments to deal with price and income volatility for farmers than those available through the CAP. While the EU provides direct payments to support the income that farmers receive from the market for their products, the U.S. terminated their system of direct payments and now focuses on market income, while reducing the risks for farmers by promoting the use of insurances. These differences become clear when we look at the respective weight of different instruments in the US and the EU: while the US agricultural policy consists of at least 60% insurance tools and no direct payments, the CAP only involves less than 1% insurance instruments and 60% income support through direct payments. [46]

c) Brazil

Brazil is a major player on international agricultural markets, being the third largest exporter of agricultural products behind only the European Union and the United States. [47] After the elimination of its import substitution policies, Brazil has moved away from taxing its agricultural sector in the 1980s and 1990s towards providing a moderate level of support to its farmers. [48] As a result, the country has seen its agricultural activities grow strongly in the last three decades. Due to productivity improvements, agricultural output has doubled and livestock production has trebled since 1990. [49] [50]

The Brazilian agricultural policy is characterised by a dual structure, as it is designed by two separate Ministries: the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Procurement (MAPA) focuses on commercial agriculture, while the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA) deals with small-scale family farmers. [51] They have created three main policy instruments to help farmers to cope with price and income volatility: rural credit, minimum price guarantees and agricultural insurance subsidies. [52]

Rural credit is the main source of government support to both commercial and family farmers. The National Rural Credit System (Sistema Nacional do Credit Rural, SNCR) provides loans to farmers at preferential interest rates by intervening in the financial system. Through several credit allocations, the MAPA aims to improve the marketing, working capital, and investments of commercial farms. Specific programmes include the Programa ABC, Moderagro, Moderinfra, Moderfrota, PSI Rural, Prodecoop, Pronamp, Procap-Agro, Inovagro and PCA. Credit for family farms for working capital and investment loans is provided by the PRONAF-Credit programme of the MDA. [53]

The preferential interest rates on these credit loans are funded by the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) and ‘compulsory resources’ (Exigibilidade dos Recursos Obrigatórios). The latter means that Brazilian Banks are obliged to use at least 34% of their deposits for loans to agricultural activities at an interest rate below the market price. In order to ensure these preferential loans, the government can compensate banks by paying (a part of) the costs for reducing the interest rate. [54]

Specific agricultural sectors benefit significantly from these rural credit programmes and targeted fiscal policies. For instance, the Brazilian government strongly encourages the production of biofuels through these instruments. In particular, concessional credit programmes are provided to oilseeds and biofuel crop producers, ethanol storages are publicly funded through the Moderinfra programme, and a special credit line for sugar producers (Prorenova) was created to overcome the shortage of sugar in the ethanol industry. The consumption of biofuel has also been promoted through tax cuts for owners of cars running on combinations of ethanol and diesel. [55]

Furthermore, since a high amount of outstanding debt is a longstanding issue in Brazilian agriculture, credit support has also been provided to producers through debt rescheduling. For both large- and small-scale farmers, there have been several debt renegotiations throughout the 1990s and 2000s, which involved reductions in interest rates on overdue debt and extensions of the repayment terms. [56]

These concessional credit programmes have expanded consistently in the last years, reaching 76 billion dollars in 2014. Of this amount, 87% was allocated to commercial agriculture, while only 13% went to family farms. The subsidies for this credit provision are estimated to have reached 10 billion dollars for the year 2014. [57]

Minimum guaranteed prices also continue to be a significant pillar of the Brazilian agricultural policy, and aims at protecting farmers against sharp drops in market prices. The National Food Supply Agency (Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento, CONAB) is the regulatory agency in charge of the implementation of this policy. [58]

For commercial agriculture, this price support is distributed regionally by the CONAB through the PGPM (Política de Garantia de Preços Mínimos). Specific price support measures for large-scale farming include direct government purchases (Aquisição de Governo Federal, AGF) and financial support for storages by the FEPM (Financiamento para Estocagem de Produtos Agropecuários integrates de Política de Garantia de Preços Mínimos). [59]

Instruments targeting the prices for small-scale farmers also include government purchases (Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos, PAA) and minimum price programmes (Programa de Garantia de Preços para a Agricultura Familiar, PGPAF). For the government purchases, the CONAB directly buys agricultural products from family farms at market prices, and distributes these as part of food programmes or uses them to replenish their food stocks. Meanwhile, the minimum price programmes ensure that farmers receive a guaranteed price for their products based on their production costs. [60]

The price guarantee instruments cover more than thirty crops, including cotton, maize, rice, soybeans and wheat, but also regional crops such as açaí, cassava, beans, guaraná, sisal, and some livestock products such as milk and honey. Examples of support prices per tonne include 231 dollars for wheat, 128 dollars for corn and 224 dollars for rice in 2015. [61] In order to finance these instruments, the Brazilian government spent 2.5 billion dollars on the measures for commercial agriculture and 516 million dollars for small-scale agriculture in 2014. [62]

Finally, the Brazilian government also aims to mitigate fluctuations in farmers’ incomes by supporting combined and yield insurances. This form of support is implemented through 4 main programmes which either pay a share of the farmers’ insurance premium or compensate them for production losses caused by natural disasters. [63]

For commercial farms, the MAPA manages the general agriculture insurance programme (Programa de Garantia da Atividade Agropecuária, PROAGRO) and the rural insurance premium programme (Programa de Subvenção ao Prêmio do Seguro Rural, PSR).

The general PROAGRO programme is designed to help producers who have troubles to finance their rural credit due to heave income losses caused by natural disasters and diseases. Farmers pay a premium fee to this programme based on a variety of indicators (the type of crop, the applied technology, the area of production etc.). When the MAPA decides that the crop failures are significant enough, farmers are exempt from the financial obligations on their rural credit. [64]

The rural PSR programme subsidises the premiums that commercial farms have to pay to the insurance companies authorised by the MAPA. State contributions depend on the type of crop, and vary between 40% (for livestock, forestry and aquaculture) and 70% (for beans, wheat and corn). [65]

Small-scale agriculture is supported through the family agriculture insurance (PROAGRO-MAIS/SEAF) and the crop guarantee programme (Programa Garantía-Safra, GS). [66]

PROAGRO-MAIS, also called SEAF, is a part of the PROAGRO programme, and also protects farmers against the loss of income as a result of natural phenomena. When the losses of the small-scale farmers participating in this programme exceed 30% of the expected crop revenues, they are exempt from paying their financial obligations for rural credit. This support is limited to a maximum of 660 dollars per farmer. Moreover, the government subsidises 75% of the premium for the programme. [67]

Finally, family farms in specific areas in the Northeastern and Southeastern regions of Brazil can participate in the GS programme. Farmers pay a fixed amount of 225 dollars every year, and can receive compensations if their registered production losses for crops of beans, cassava, cotton, corn or rice are higher than 50%. [68] [69]

In 2014, commercial agricultural producers received 645 million dollars in insurance subsidies through the general insurance programme and 300 million dollars through the rural insurance programme. Support for small-scale family farms under the PROAGRO-MAIS-SEAF programme amounted to more than 1.3 billion dollars. [70]

In short, domestic support to Brazilian agricultural producers is provided mainly through subsidised credit, and complemented by price support measures and insurance policies, which aim at stabilising the prices for agricultural products and protecting the incomes of both large-scale and family farmers.

d) China

China has not only become the largest agricultural producer in the world, but is also a large net importer of agro-food products, as it feeds almost one fifth of the global population. The financial support for its agricultural sector has increased significantly in the last decade and continues to grow every year. [71]

The main instruments of the Chinese agricultural policy consist of minimum guaranteed prices for wheat and rice, and ad hoc market interventions for other agricultural commodities. In combination with tariffs, tariff rate quotas (TRQs), and government controls, these instruments ensure that farmers receive a minimum level of prices for their products. Additionally, a variety of other programmes gives further financial support to Chinese farmers: direct payments for grain producers; subsidies for agricultural inputs (fertilisers and energy), improved seeds, and machinery; and financial contributions to agricultural insurance schemes. [72]

Minimum guaranteed prices for grains are determined by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), in close cooperation with the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and other state institutions. Price guarantees are limited to the biggest grain-producing provinces and differ for the various types of grain. In 2015, average support prices per tonne are estimated at 384 dollars for wheat, 361 dollars for corn and 438 dollars for rice. [73]

Intervention purchases are made by the state-owned China Grain Reserves Corporation (Sinograin) if the market price for wheat, corn and rice drops below certain levels. This requires large public stocks, which are managed by the State Grain Administration. The current level of grain reserves amounts to 40% of China’s domestic consumption, which is more than in any other country in the world. The cost of maintaining these stocks was 8.8 billion dollars in the year 2013. [74]

For other agricultural commodities, ad hoc market interventions are possible at fixed prices, although these are not always executed and there are significant regional differences. Nevertheless, in recent years policy reforms abandoned the stocks for cotton and soybeans, and replaced them with a system of compensatory direct payments if prices fall below a certain level. This type of reform could be extended to other commodities in the future.

The amount of budget transfers provided through these price interventions has risen significantly since the end of the 1990s, as the minimum prices have been increased every year. [75] In 2014, the Chinese government bought 365 million tonnes of agricultural commodities from its farmers, representing one third of the country’s total agricultural expenditure. As a result of these measures, Chinese farmers receive prices for their products which are 20% higher than those on the world markets. [76]

Furthermore, tariffs on agricultural products amount to 15% on average, and several agricultural products are also subject to tariff rate quotas, including wheat, maize, rice, wool, cotton and certain types of fertilisers. [77]

Grain producers also receive direct payments to support their production and stabilise their incomes. They are paid at a flat rate per unit of land, which consists of 24 or 36 dollars per hectare, depending on the region. Government spending on these direct payments involves 2.4 billion dollars per year.

Subsidies on agricultural inputs are provided to compensate grain producers for increasing prices of fertilisers, energy, and fuel. Again, fixed payments are made based on the amount of land, and they directly support farmers’ incomes.

The Improved Seed Variety Subsidy programme provides subsidies for farmers to enable them to improve the quality of their seeds. The implementation of this subsidy depends on the product: while the national government makes cash payments based on land for rice, maize and rapeseed, the provinces can make direct payments or reductions on the prices of seeds for wheat, soybean and cotton. Farmers receive 24 or 36 dollars per hectare, depending on the commodity. However, it is not monitored if these funds are actually being used for seed purchases.

The purchases of agricultural machinery are also being increasingly subsidised, through a programme that compensates the buyer or seller for 30% of the price. This subsidy programme currently covers 12 categories and 48 sub-categories of machines. In theory, state contributions are limited to 7 900 dollars per single item, but these subsidy ceilings are never enforced in practice.

The budgetary transfers for these programmes involved 17.1 billion dollars for agricultural inputs, 3.5 billion dollars for improving the seed quality, and 3.5 billion dollars for the purchases of machinery in 2014. [78]

Finally, there are several combined insurance schemes for both crops and livestock at the regional level. In 2013, these covered 73 million hectares of agricultural land, which is almost half of the total crop area. The insurances are provided by 25 eligible private corporations, while the costs for the premium are shared between the central government, the regional governments and the agricultural producers themselves. There are some variations in the triggers for payment claims, as these are decided at the regional level (for example, in the Shandong Province the yield losses for wheat should be higher than 40%). [79] The percentage of subsidies also varies for different agricultural commodities, but cover the premiums for a minimum of 60% for crops and 70% for livestock. [80]

Subsidies for agricultural insurance have expanded in recent years, and China has become the second largest agricultural insurance market in the world, after the United States. Contributions of the central government amounted to 3.6 billion dollar in 2013, while 33.7 billion households benefited from these insurance schemes for an amount of 3.4 billion dollars. [81]

e) Australia

Australia is an important producer and exporter of agricultural commodities and has a consistently large surplus for agro-food trade. Since the 1980s, the country’s market price support to its agricultural producers has been gradually eliminated and replaced by more targeted payments. As the tariffs on imports of agriculture and food products are also very low, the Australian farming industry is now strongly market-oriented. [82]

Today, the Australian agricultural policy is mainly focused on assisting farmers to manage several production risks. While half of the agricultural budget is also spent on support to general services, environmental conservation, and R&D programmes, the main policy instruments to prevent severe income losses for farmers consist of disaster assistance and tax concessions. [83]

As Australian farmers are occasionally confronted with extreme weather conditions (such as cyclones, bushfires, hail storms, floods and droughts), these risks are addressed by various disaster assistance programmes implemented by the central and local governments. [84]

The Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) is a long-standing framework that partially reimburses farmers who are confronted with damage resulting from a broad range of natural disasters (excluding droughts). The regional and local governmental levels are given flexibility to develop their own programmes within this framework, while the indemnities themselves are paid by the central government if certain thresholds are exceeded. Reimbursements usually involve 50% of the losses, and are triggered for ‘small disasters’ if the damage in a state exceeds 170 000 dollars, and for ‘severe impact events’ if these are approved by the Australian Prime Minister. [85]

In 2014, a number of additional assistance measures have been introduced through the Intergovernmental Agreement on National Drought Program Reform between the federal, state and territory governments. This new approach replaced the existing arrangements for droughts and is now focused on different causes of financial hardship for farmers. In particular, the Farm Household Allowance programme was created to provide income support payments to farmers who experience financial hardship, regardless of its reasons (so not limited to natural disasters). The reimbursements of this programme do not rely on triggers, but depend on the financial position of each farm, which is determined by a Farm Financial Assessment. [86]

The Intergovernmental Agreement of 2014 also extended several tax concessions to agricultural producers. There is now improved access for farmers to the Farm Management Deposits Scheme, which aims to smoothen income fluctuations for farmers and improve their long-term financial security. The amount of money on these deposits should be at least 700 dollars and not more than 285 000 dollars, and is exempt from several tax obligations. Moreover, the Farm Finance Concessional Loans Scheme was extended, providing additional concessional loans with subsidised interest rates in a number of states. These loans can be used for debt restructuring, to fund operating expenses, and for drought recovery and preparedness activities. Finally, tax incentives are also provided to promote investments and sustainable production systems. [87] [88]

In 2014, the Australian government spent 157 million dollars on disaster assistance programmes and 308 million dollars on tax concessions, and together these programmes amount to more than half of the total agricultural policy budget of 830 million dollars. [89]

-

Conclusion

Due to market conditions and climatic factors, prices for agricultural products tend to fluctuate significantly, causing a high level of income uncertainty for farmers around the world. These variations in price and income were especially high in the last decade, which triggered a renewed debate on possible ways to tackle these issues.

Against this background, this report focused on the policies and instruments used in the leading agricultural countries and regions to support farmers in managing these risks. This analysis demonstrated that the evolutions in agricultural policies have significantly diverged between the major agricultural countries. [90]

On the one hand, developing countries have generally evolved from taxing their agricultural sector in the 1990s to providing significant levels of support to their farmers. For instance, Brazil eliminated its import substitution policy in the 1980s and 1990s, and now protects its farmers against sharp drops in revenues through rural credit programmes, minimum price guarantees, and agricultural insurance subsidies. China has also significantly increased its agricultural support in the last decade, and currently adopts a broad range of support measures, including minimum guaranteed prices, ad hoc market interventions, tariffs, subsidies, and increasing financial support for insurance schemes.

On the other hand, the historically high level of price support in developed countries has been replaced by less market-distorting policies. In the EU, the traditional price support policy of the CAP was dismantled throughout several reforms, and direct decoupled payments are now the main policy tool that shield European farmers from severe income fluctuations. Initially, the United States underwent the same transformation from price support schemes towards direct payments, yet these were completely eliminated with the Farm Bill of 2014. Instead, the US agricultural policy for the period 2014-2018 continues to promote the use of agricultural insurance through several state-supported programmes. Australia has also gradually adapted a more market-oriented approach, supporting its farmers dealing with production risks through disaster assistance programmes and tax concessions.

Finally, special attention has been devoted in this report to agricultural insurance schemes. While the United States and China currently have the largest agricultural insurance markets in the world, and Brazil and Australia have consistently increased their support for these instruments in the last years, agricultural insurances are still underdeveloped and diverge widely between the EU member states. Despite the fact that the 2009 and the 2014 CAP reforms introduced instruments to reinforce agricultural insurances, these are currently still weak ‘options’ for member states rather than full-fledged programmes. However, this situation might change in the future, as the European Commission has the opportunity to step up these instruments in the context of the mid-term evaluation of the CAP in 2018

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

AGRI-VIEW, How does the margin protection program impact dairy producers, http://www.agriview.com/news/dairy/how-does-the-margin-protection-program-impact-dairy-producers/article_f57408ae-5f8e-5820-9895-0defc34f2eae.html.

Ahmed, O. and Serra, T. ‘Economic analysis of the introduction of agricultural revenue insurance contracts in Spain using statistical copulas’, Agricultural Economics, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2015, pp. 69-79.

Antón, J. and Kimura, S. ’Risk Management in Agriculture in Spain’, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 43, pp. 1-63.

Australian Government, Farm Household Allowance, http://www.humanservices.gov.au/customer/services/centrelink/farm-household-allowance.

Australian Government, Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements,

http://www.disasterassist.gov.au/FactSheets/Pages/NaturalDisasterReliefandRecovery Arrangements.aspx.

Bielza, M. et al., ‘Risk Management and Agricultural Insurance Schemes in Europe’, JRC Reference Reports, 2009, pp. 1-27.

DG Agriculture, Agricultural Insurance Schemes, 2008.

Dönmez, A. and Magrini, E. ‘Agricultural Commodity Price Volatility and its Macroeconomic Determinants’, JRC Technical Reports, 2013, pp. 1-27.

DTB Associates, Agricultural Subsidies in Key Developing Countries, 2014.

European Commission, ‘Overview of CAP Reform 2014-2020’, Agricultural Policy Perspectives Brief, No. 35, 2013, pp. 1-10.

European Commission, Trends in EU-Third Countries trade of milk and dairy products, 2015.

European Parliament Think Tank, Comparative Analysis of Risk Management Tools supported by the 2014 Farm Bill and the CAP 2014-2020, 2014.

FAO, Food and Nutrition in Numbers, 2014, p. 8.

FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011.

FAPDA, Country Fact Sheet on Food and Agricultural Policy Trends, April 2014.

Garcia, R. Rural Insurance in Brazil, http://thebrazilbusiness.com/article/rural-insurance-in-brazil.

GFDRR, Coping with losses: options for Disaster risk financing in Brazil, 2014.

Hofstrand, D. ’Can we meet the world’s growing demand for food?’, AgMRC Renewable Energy & Climate Change Newsletter, February 2014.

House of Commons, ‘The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013’, Fifth Report of Session 2010–11, 2011, pp. 1-79.

Jie, C. Li, Y. and Sija, L. ‘Design of Wheat Drought Index Insurance in Shandong Province’, International Journal of Hybrid Information Technology, Vol. 6, No. 4, 2013, pp. 95-104.

Landini, S. Agricultural risk and its insurance in Italy, 2015.

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply, Brazil Agricultural Policies, 2008.

Nicholson, C. and Stephenson, M. ‘Dynamic Market Impacts of the Dairy Margin Protection Program of the Agricultural Act of 2014’, Working Paper Number WP14-03, 2014, pp. 1-33.

OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, 2015.

OECD, ‘Brazilian Agricultural Policy: Structural Change, Sustainability and Innovation’, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, 2015, pp. 83-101.

OECD, Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Australia, 2015.

OECD-FAO, Agricultural Outlook 2015, 2015.

Swinnen, J., Knops, L. and Van Herck, K. ‘Food Price Volatility and EU Policies’, WIDER Working Paper, No. 32, 2013, pp. 1-33.

Tangermann, S. ‘Risk Management in Agriculture and the Future of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy’, ICTDS Issue Paper, No. 34, 2011, pp. 1-41.

Tao, L. China’s Agricultural Insurance is Catching Up, July 2014.

World Bank, Government Support to Agricultural Insurance Challenges and Options for Developing Countries, 2010.

Notes

[1] J. Swinnen, L. Knops and K. Van Herck, ‘Food Price Volatility and EU Policies’, WIDER Working Paper, No. 32, 2013, p. 1.

[2] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, p. 6.

[3] FAO, Food and Nutrition in Numbers, 2014, p. 8.

[4] D. Hofstrand, ‘Can we meet the world’s growing demand for food?’, AgMRC Renewable Energy & Climate Change Newsletter, February 2014.

[5] S. Tangermann, ‘Risk Management in Agriculture and the Future of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy’, ICTDS Issue Paper, No. 34, 2011, p. 11.

[6] Ibid., p. 4.

[7] Ibid., p. 2.

[8] A. Dönmez and E. Magrini, ‘Agricultural Commodity Price Volatility and its Macroeconomic Determinants’, JRC Technical Reports, 2013, p. 1.

[9] European Parliament Think Tank, Comparative Analysis of Risk Management Tools supported by the 2014 Farm Bill and the CAP 2014-2020, 2014, p. 13.

[10] Ibid, pp. 21-22.

[11] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, p. 11.

[12] Tangermann, op.cit., p. 3.

[13] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., p. 21.

[14] Tangermann, op. cit., p. 12.

[15] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., pp. 21-22.

[16] Tangermann, op.cit., pp. 21-22.

[17] Swinnen et al., op.cit., p. 33.

[18] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., pp. 21-22.

[19] Swinnen et al., op.cit., pp. 35-38.

[20] European Commission, ‘Overview of CAP Reform 2014-2020’, Agricultural Policy Perspectives Brief, No. 35, 2013, p. 4.

[21] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., p. 39.

[22] Swinnen et al., op.cit., pp. 61-62.

[23] House of Commons, ‘The Common Agricultural Policy after 2013’, Fifth Report of Session 2010–11, 2011, p. 34.

[24] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., p. 39.

[25] Swinnen et al., op.cit., p. 68.

[26] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit, pp. 55-56.

[27] Ibid., pp. 47-48.

[28] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., p. 39-46.

[29] Tangermann, op.cit., p. 21.

[30] J. Antón and S. Kimura, ‘Risk Management in Agriculture in Spain’, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 43, p. 22.

[31] M. Bielza et al., ‘Risk Management and Agricultural Insurance Schemes in Europe’, JRC Reference Reports, 2009, p. 10.

[32] Ibid., pp. 12-13.

[33] O. Ahmed and T. Serra, ‘Economic analysis of the introduction of agricultural revenue insurance contracts in Spain using statistical copulas’, Agricultural Economics, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2015, p. 70.

[34] Antón and Kimura, op.cit., p. 21.

[35] Ibid., pp. 22-24.

[36] S. Landini, Agricultural risk and its insurance in Italy, 2015, p. 41.

[37] Bielza et al., op.cit., p. 13.

[38] DG Agriculture, Agricultural Insurance Schemes, 2008, pp. 192-200.

[39] European Parliament Think Tank, op. cit., pp. 29-30.

[40] Ibid., p. 19.

[41] Ibid., pp. 33-34.

[42] European Commission, Trends in EU-Third Countries trade of milk and dairy products, 2015, p. 25.

[43] C. Nicholson and M. Stephenson, ‘Dynamic Market Impacts of the Dairy Margin Protection Program of the Agricultural Act of 2014’, Working Paper Number WP14-03, 2014, p. 1.

[44] AGRI-VIEW, How does the margin protection program impact dairy producers, http://www.agriview.com/news/dairy/how-does-the-margin-protection-program-impact-dairy-producers/article_f57408ae-5f8e-5820-9895-0defc34f2eae.html.

[45] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., pp. 34-36.

[46] Ibid., pp. 13-14.

[47] FAPDA, Country Fact Sheet on Food and Agricultural Policy Trends, April 2014, p. 1.

[48] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, 2015, pp. 88-91.

[49] OECD-FAO, Agricultural Outlook 2015, 2015, p. 62.

[50] OECD, op.cit., p. 87.

[51] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., p. 37.

[52] OECD-FAO, op.cit., p. 93.

[53] OECD, op.cit., p. 86.

[54] OECD-FAO, op.cit., p. 94.

[55] OECD, ‘Brazilian Agricultural Policy: Structural Change, Sustainability and Innovation’, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, 2015, pp. 88-89.

[56] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 218.

[57] European Parliament Think Tank, op.cit., p. 38.

[58] FAPDA, op.cit., pp. 2-3.

[59] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 90.

[60] OECD-FAO, op.cit., p. 94.

[61] DTB Associates, Agricultural Subsidies in Key Developing Countries, 2014, p. 2.

[62] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 91.

[63] OECD, Brazilian Agricultural Policy: Structural Change, Sustainability and Innovation, op.cit., p. 88.

[64] Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply, Brazil Agricultural Policies, 2008, p. 26.

[65] OECD, Brazilian Agricultural Policy: Structural Change, Sustainability and Innovation, op.cit., p. 88.

[66] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 91.

[67] World Bank, Government Support to Agricultural Insurance Challenges and Options for Developing Countries, 2010, p. 106.

[68] R. Garcia, Rural Insurance in Brazil, http://thebrazilbusiness.com/article/rural-insurance-in-brazil.

[69] GFDRR, Coping with losses: options for Disaster risk financing in Brazil, 2014, p. 42.

[70] OECD-FAO, op.cit., p. 95.

[71] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., pp. 113-114.

[72] Ibid., p. 116.

[73] DTB Associates, op.cit., 2014, p. 2.

[74] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 117.

[75] Ibid., pp. 112-119.

[76] Ibid., pp. 114-117.

[77] Ibid., p. 121.

[78] Ibid., p. 119.

[79] C. Jie, Y. Li and L. Sija, ‘Design of Wheat Drought Index Insurance in Shandong Province’, International Journal of Hybrid Information Technology, Vol. 6, No. 4, 2013, p. 100.

[80] L. Tao, China’s Agricultural Insurance is Catching Up, July 2014, p. 17.

[81] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 120.

[82] Ibid., pp. 79-80.

[83] Ibid., p. 82.

[84] OECD, Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Australia, 2015, p. 109.

[85] Australian Government, Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements,

http://www.disasterassist.gov.au/FactSheets/Pages/NaturalDisasterReliefandRecovery Arrangements.aspx.

[86] Australian Government, Farm Household Allowance, http://www.humanservices.gov.au/customer/services/centrelink/farm-household-allowance.

[87] OECD, Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Australia, op.cit., pp. 110-113.

[88] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., pp. 78-83.

[89] OECD, Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Australia, op.cit., p. 109.

[90] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2015, op.cit., p. 1.