Timmermans dreamed it, von der Leyen did it. If the European Commission had wanted to fuel populism and misunderstanding in rural areas, it could not have done a better job:

– nearly a 20% cut in the CAP budget (integrating the new ring-fenced parameters);

– the integration of the Common Agricultural Policy into the Single Fund ;

– an extensive greening via the Performance framework of the policy undermining its economic dimension;

– a renationalisation of this policy via an “à la carte” approach without any serious common mechanism.

This initial proposal is a major blow to European agriculture and to all farmers who expressed their dismay just over a year ago. Therefore, Farm Europe calls upon the EU co-legislators and key decision-makers, the Member States and the European Parliament, to correct the course of action, and push back this proposal to revive European ambition and vision.

The stubbornness of European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, in sidestepping any debate on the future of the Common Agricultural Policy shows her determination to fundamentally undermine the uniqueness of this policy and her clear lack of understanding of its economic importance for the EU rural economy.

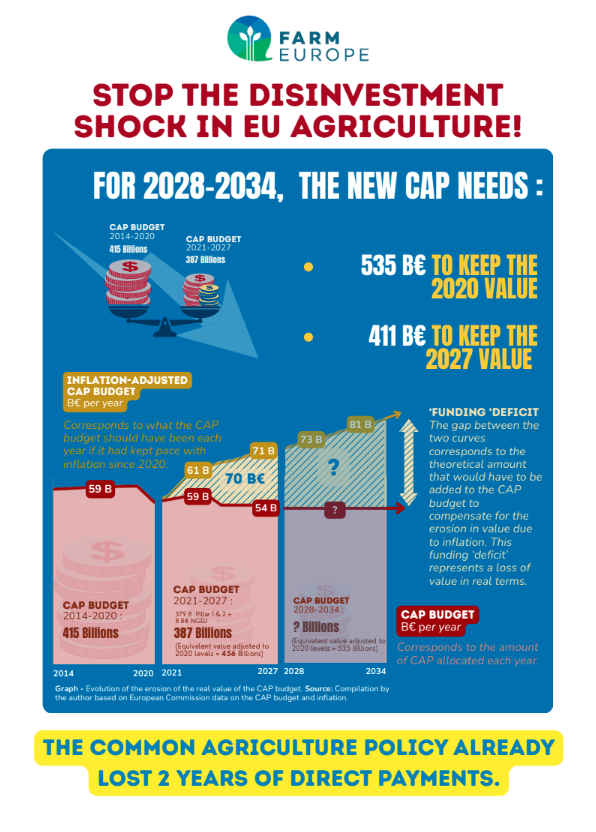

While EUR 482,5 billion are needed to maintain the CAP budget at its 2020 level, or EUR 395 billion to maintain its 2027 level, the Commission’s proposal of EUR 300 Billion makes farmers the big losers of Ursula von der Leyen’s legacy since 2021. The doubling of the crisis reserve at 6,3 billion EUR is the only positive step to acknowledge in a very sad day for EU agriculture.

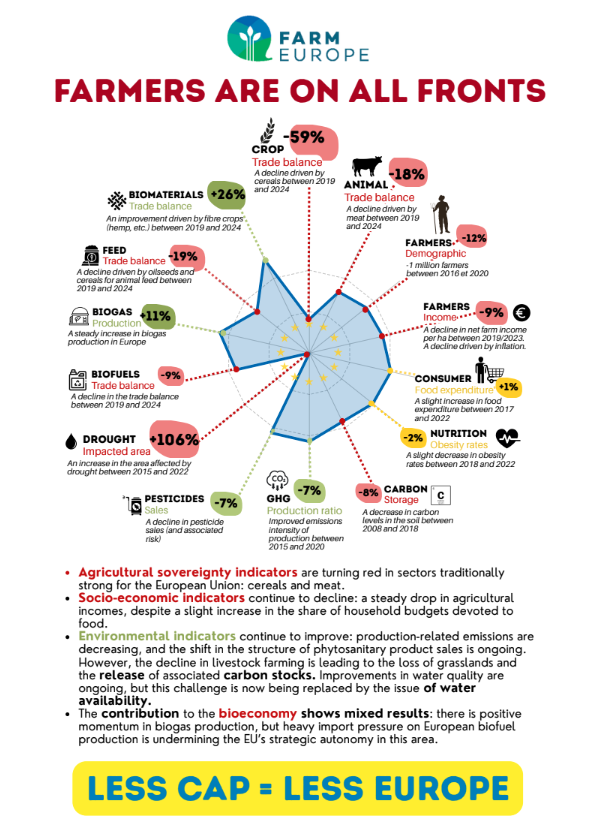

The desire to subordinate the CAP to a single performance framework covering all EU policies is clear in this regard. The single performance framework denies the economic nature of the European Agricultural Policy through 32 exclusively environmental and social indicators, a far cry from the statements on strategic autonomy and food security made to the sector not so long ago.

The « Do No Harm » concept seems to be generalised to all CAP funding without clear guidance on the consequences of this principle and a double conditionality is set in the European Commission proposal via the 27 different cross-compliance mechanisms (Article 3) and a new general provision prioritising environment and climate as exclusive priorities for the CAP. The fundamental economic dimension of the CAP is being sidelined, and the level playing field obliterated.

Furthermore, the residual framework reserved for the specific nature of CAP rules increases the risk of renationalisation and reinforces the perception of marginal nature of the future of this policy as envisaged by the President of the European Commission, which is far from being commensurate with the vital challenges facing rural areas.

In this regard, Farm Europe condemns a political direction that is dangerous for the European project as such, and calls on the Member States and the European Parliament to save the unique link between the European Union, its citizens and its farmers at a time when the institution responsible for the European general interest seems to be abandoning it.

On the specific CAP provisions (subject to the assessment of the final draft regulations not available at the time of this press release):

- The focus on “those who need it most” marginalises the tools of the Common Agricultural Policy. Even if we welcome the priority given to those who produce. The parameters established for degressivity and capping are disconnected from the reality of European agriculture and send a message that runs counter to the desire to focus the CAP on those who produce.

- The renewal of production-linked payments shows that the issue of production is being taken into account, as is the importance of having income support differentiated according to territory. However, the almost total absence of common parameters to define these payments paves the way for significant distortions that would put farmers in competition with each other.

- The green architecture has been turned upside down, with a generalised conditionality mechanism, submission to global environmental, climate and social performance indicators (performance framework), the “Do no harm” principle and the obligation for Member States to prioritise environmental and climate objectives (Article 4). Two types of measures are planned for environmental commitments and voluntary transition measures, the latter being capped at EUR 200,000. The lack of a common EU baseline is, again, a direct threat to the level playing field.

- Finally, the Commission’s willingness to emphasise the development of a genuine risk management policy in all EU Member States, which must be accompanied by a real European crisis reserve, is to be welcomed. The functioning of this reserve needs to be urgently clarified to enshrine its effectiveness in stone, rather than just making empty promises. Similarly, the change of direction on the issue of livestock farming is also worth highlighting, in particular the possibility of fully exploiting grass and protecting meat designations.

- At this stage, the desire to accelerate the digitalisation of agriculture is also clearly stated, but this has not yet been translated into sufficiently robust tools to fully realise the potential of these transformations.