There have always been predictions and concerns about the ability of agriculture to meet the global demand for food. In as early as 1798, Thomas Malthus made a pessimistic analysis of this issue in his groundbreaking ‘Essay on the Principle of Population’. He started from the observation that the global population would continue to rise exponentially, while the production of food could only be increased in a more limited way. As a result, he predicted that mankind would eventually be unable to feed an increasing number of people, leading to famine, war and misery. [1]

Fortunately, this ‘Malthusian catastrophe’ never took place on a global scale. Because of an increase in agricultural productivity due to technological innovations, the production of food was able to keep pace with demographic growth in the last two centuries. [2]

However, today there are renewed concerns that global food production will be increasingly challenged by a growing demand for agricultural products.

This revived interest in the resilience of the agricultural sector was driven by several recent events and phenomena, such as increasingly variable weather conditions due to global warming and large variations in food and energy prices. These are only some of the factors which could place an unprecedented pressure on the global food system in the future. [3] Within this context, it is important to gain a better understanding of how we may achieve food security for the next decades.

This article aims to offer insights into this topic by providing an overview of the major factors which will drive the global demand and supply for food, as well as some of the obstacles for the agricultural sector to respond to these challenges. In order to do this, it will present an analysis of data and projections provided by several researchers and international organisations, and in particular the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO).

In the first chapter, the two key drivers for food demand will be discussed, namely global population growth and changing consumption patterns. As these two developments will significantly increase the worldwide need for food, an estimate will be made on how much additional production of agricultural commodities these evolutions would require.

The second part will examine how the supply of food could be increased in order to respond to this surge in food demand. The three possible solutions which will be considered are an expansion of the land for food production, an increase in the agricultural productivity, and further investments in the agricultural sector.

Finally, some additional issues will be addressed that could impact the ability of agriculture to meet the future food needs. These include the limited access of farmers to finance, the fluctuations in the prices for agricultural commodities, and food wastage.

- Rising food demand and its driving forces

Population growth

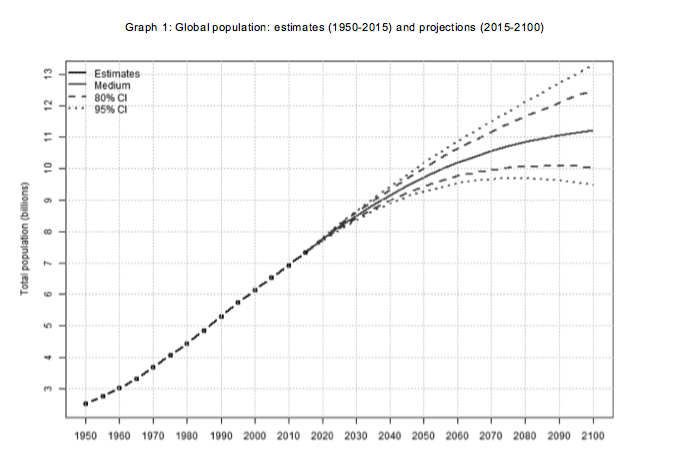

The main evolution that will increase the demand for food is a continued rise in the number of people on our planet. While the world’s population consists of 7.3 billion people today, the UN projects that this number will increase by 1.2 per cent annually, amounting to 8.5 billion people in 2030 and almost 10 billion people in 2050 (see Graph 1). [4]

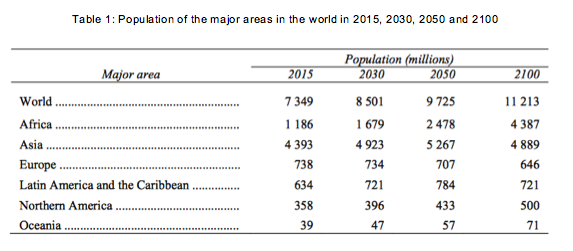

Most of this population growth is projected to occur within the developing countries, and especially in Africa and Asia (see Table 1). [5] Of the additional 1.15 billion people that will be added to the global population between now and 2030, 46% will be added in Asia and 42.79% in Africa. In the longer term, Africa is expected to be the largest contributor, accounting for more than half of the global population growth by 2050.

Additionally, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, and Oceania are expected to have only minor increases, while Europe is the only continent that will see its population decrease in the future.

Because these demographic projections have a high degree of certainty, it is inevitable that the world’s population will grow rapidly in the short to medium term. As a result, this will lead to a major increase in the consumption of food in the coming decades and will impose profound challenges to meet the global demand for agricultural products. [6]

Consumption patterns

Global population growth will be accompanied by a change in consumption patterns of people worldwide, and especially of those living in developing countries. The two major factors driving this transformation in food consumption will be the rising incomes of these individuals and a trend towards increased urbanisation. [7]

First, the rising incomes of the people living in developing countries will stimulate dietary change, as they will be increasingly capable of buying high-quality food. [8] Secondly, urbanisation is expected to accelerate in both the developed and developing world, in the sense that there will be large movements of people moving from rural to urban areas. Between now and 2050, the share of the world’s population living in urban areas is expected to rise from 50% to 70%. [9] This increased urbanisation will prompt additional transformations in the lifestyles and consumption patterns of people. [10]

As a result of these two developments, global diets will become increasingly similar, since people who were living mainly on vegetable diets will now consume more meat, fish, dairy products, fruits and vegetables. This pattern is already emerging in the Asian developing countries today. [11]

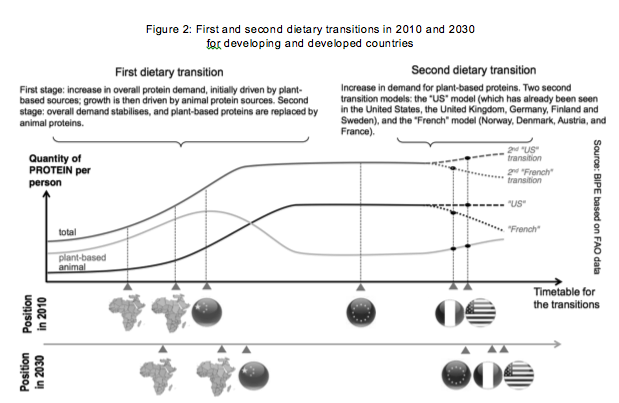

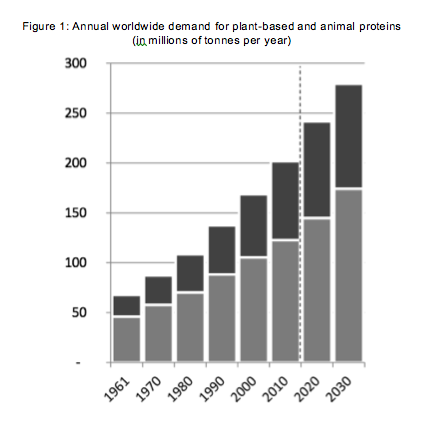

In terms of protein consumption, this will imply a global shift from plant-based to animal-based sources of proteins (see Figure 1). In this respect, a report made by BIPE argues that the developing world will continue to undergo a ‘first dietary transition’ in the next 15 years. This means that the overall demand for proteins will continue to increase in these regions. Initially, this will be caused by a higher consumption of plant-based proteins, but these will be increasingly replaced by more animal-based protein sources. On the other hand, the developed world will experience a ‘second dietary transition’: their demand for proteins has already stabilised and their consumption of plant-based proteins is expected to increase again. However, it is difficult to predict how the demand for animal-based proteins will evolve within these developed regions, as there will be diverging national trends. While the consumption of meat will stabilise in some high-income (the ‘US transition’), the demand for animal-based proteins might decline in others (the ‘French transition’) (see Figure 2). [12]

In terms of protein consumption, this will imply a global shift from plant-based to animal-based sources of proteins (see Figure 1). In this respect, a report made by BIPE argues that the developing world will continue to undergo a ‘first dietary transition’ in the next 15 years. This means that the overall demand for proteins will continue to increase in these regions. Initially, this will be caused by a higher consumption of plant-based proteins, but these will be increasingly replaced by more animal-based protein sources. On the other hand, the developed world will experience a ‘second dietary transition’: their demand for proteins has already stabilised and their consumption of plant-based proteins is expected to increase again. However, it is difficult to predict how the demand for animal-based proteins will evolve within these developed regions, as there will be diverging national trends. While the consumption of meat will stabilise in some high-income (the ‘US transition’), the demand for animal-based proteins might decline in others (the ‘French transition’) (see Figure 2). [12]

In general, however, it is expected that these dietary transitions will lead to a significant increase in the global demand for meat by 2030, as growing parts of the global population will be living in developing countries and/or urban areas. Since a rise in meat consumption requires higher inputs of feed grains and oilseeds, this transformation will also fuel the demand for other agricultural commodities. [13] As most of the developing regions do not currently have the means to realise this increase in meat consumption by themselves, global agricultural output will need to keep up with this surge in demand if food security is to be achieved.

The necessary increases in the production of agricultural commodities

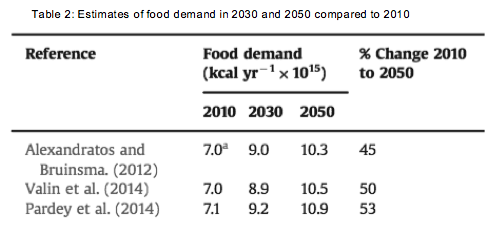

As a consequence, a growing population with changing consumption patterns will result in a sharp growth in the future demand for food. [14] According to several estimates (see Table 2), the global supply of food will have to increase by almost 30% by 2030 and around 50% by 2050 if it wants to equal the rise in global demand.[15]

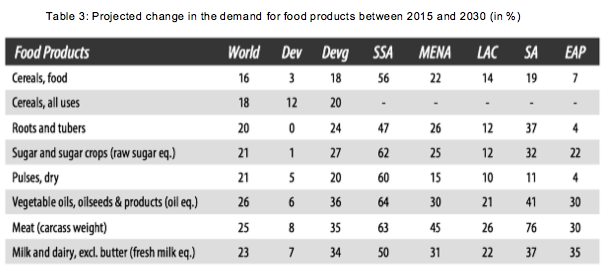

In terms of the main agricultural commodities, the additional volumes which will be required to feed the world’s population are substantial. The table below lists the expected change in demand for food for the next 15 years. Among others, global production will have to increase with 18% for cereals, 21% for sugar, 26% for vegetable oil, 25% for meat and 23% for dairy products between now and 2030. [16]

- Possibilities for additional food supply

Expanding the amount of agricultural land for food production

On the supply side of the equation, the first possibility to increase food production is by expanding the amount of farmland. According to global estimates made by the FAO, between 2010 and 2030 52 million hectares (Mha) of arable land will be added to the 1534 Mha which are already being exploited. This will amount to a rise in agricultural surfaces of 3.4% in 20 years.

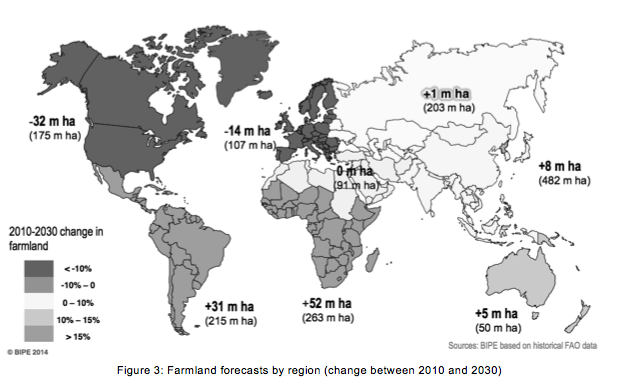

However, the FAO also expects significant geographical divergences in the evolution of these farmlands. The mobilisation of additional land will mainly take place in the developing countries: there will be an increase of 53 Mha in Sub Sahara Africa, 31 Mha in Southern and Central America, 22 Mha in South East Asia and 5 Mha in Oceania. However, this expansion will be partly offset by a decline in agricultural surfaces in the developed countries: these will diminish by 32 Mha in Northern America, 13 Mha in Europe and 14 Mha in Southern Asia (see Figure 3). [17]

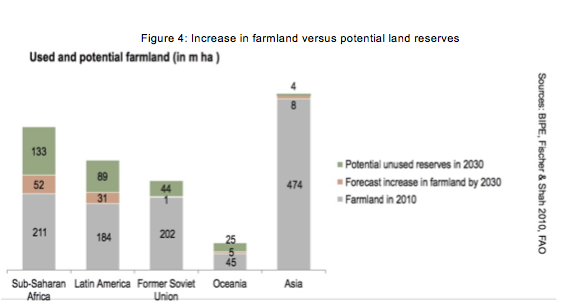

Therefore, the possibilities for further increases in arable land appear to be rather limited, since less additional land can be brought into production than in the past (see Figure 4). This means that an expansion in production area alone will probably not be

sufficient to meet the increasing demand. [18]

Moreover, it is likely that the agricultural surfaces in developing countries will be adversely affected by climate change. Since these countries are situated in zones where food production is rather vulnerable to variable weather conditions, the impact of climate change on temperatures, rainfall and weather disasters could pose a serious threat to their agricultural production capacities. On the other hand, the agricultural sector in developed countries, where farmland is expected to diminish, will be less susceptible to the effects of climate change due to better natural conditions and the use of up-to-date technologies. [19]

In short, while climate change will disadvantage the regions where more suitable land can be exploited, agricultural surfaces will shrink in the areas where weather conditions produce a higher stability. Therefore, the geographical shift in farmland could make the food supply more variable, resulting in a bigger volatility in the prices of agricultural products. This will especially be the case if developing countries are unable to improve their technologies and developed countries fail to increase their agricultural productivity growth. [20]

Increasing agricultural productivity

Meeting the future demand for food will also depend to a large extent on our ability to maintain or increase the current levels of agricultural productivity. Essentially, an increase in productivity is achieved when less agricultural input is needed to produce the same amount of agricultural output. In other words, improved agricultural productivity means a rise in the amount of agricultural output per unit of agricultural input. [21]

A common indicator for agricultural productivity is the agricultural Total Factor Productivity (TFP), which describes the ratio of agricultural output (crops and livestock) to their input (such as land, labour and machines). Similarly, an increase in TFP means that with the same amount of agricultural input, more agricultural output can be produced. [22]

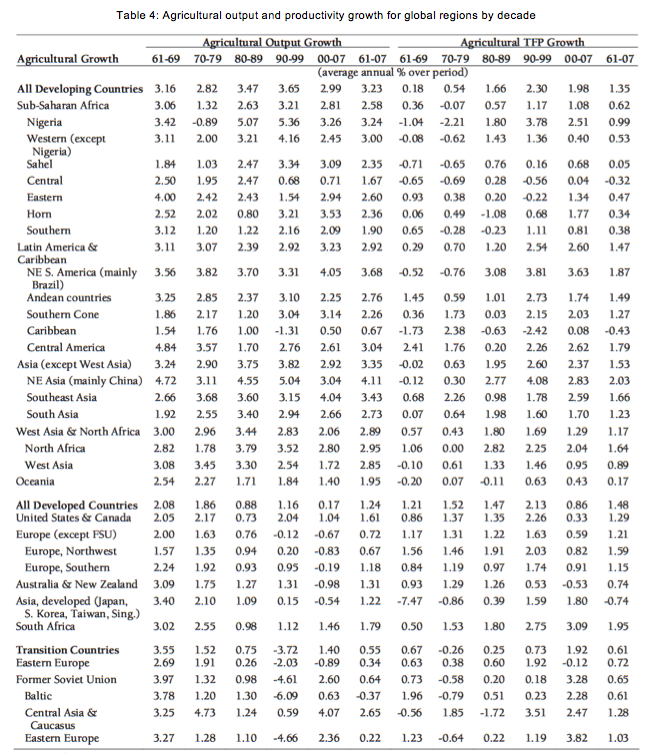

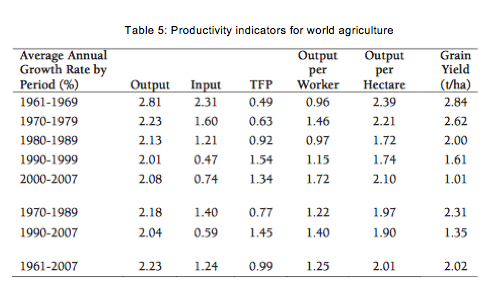

More specifically, if the global food supply has to increase with 50% by 2050, as estimated by the FAO, this would imply an annual TFP growth of 2% for the next 35 years, provided other elements remain equal. However, this seems to be a difficult task if we look at the annual rates in TFP growth for the last decades.

As the tables below indicate, the world’s agricultural Total Factor Productivity only had an annual growth rate of 0.99% from 1961 until 2007. Moreover, this global estimate involved diverging trends between the global regions. For instance, the transition countries of the former Soviet Union only experienced marginal increases in TFP growth until the end of the 1990s, followed by a strong rise in growth rates of 1.92% from 2000 until 2007. On the contrary, in developing countries the annual TFP growth rate experienced a constant increase until the 1990s, after which it slowed down to almost 2% per year for 2000-2007. The developed countries also peaked in the 1990s, achieving an annual growth of more than 2%, but slowed down afterwards to 0.86% for 2000-2007 (with annual growth rates of only 0.59% in Europe and 0.33% in the US and Canada). In general, this means that in nearly every region of the world, past TFP growth rates fell short of the expected annual 2% productivity rise in the future. [23]

Apart from Total Factor Productivity rates, some estimates have also expressed the

Apart from Total Factor Productivity rates, some estimates have also expressed the

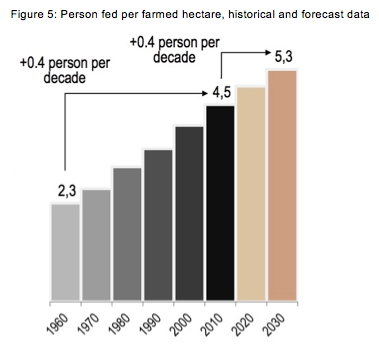

necessary short-term productivity rise in terms of the yields per agricultural area. According to the FAO, each hectare of agricultural surface has fed an additional 0.4 people per decade since 1960, and this trend should continue in the future to meet global demand for food. Since each hectare of farmland was feeding 4.5 people in 2010, this means that one hectare should provide enough food for 4.9 people by 2020 and 5.3 people by 2030 (see Figure 5). [24]

However, past performances do not guarantee that agricultural productivity will continue to rise at the same pace in the future. On the contrary, it is likely that productivity rates of developed countries will continue to grow more slowly than in the 20th century. [25] For example, data provided by DG Agriculture and Eurostat shows that while annual agricultural TFP growth was still 1.6% in the European Union between 1995 and 2002, productivity rates stagnated in the last decade, growing only by 0.6% per annum over the period 2002 to 2011. Only the new EU member states managed to achieve a significant TFP growth rate (1.6%) within this period, yet they account for only a minor share of total agricultural output in the EU. [26]

If agricultural TFP continues its sluggish growth in the European Union and the developed world, this could result in shortfalls for the necessary supply of agricultural products. Since the long term agricultural TFP growth is mainly determined by the level of private and public investment in agriculture, this will be an important element in meeting the growing global food demand by 2050.

Further investments in agriculture

Agricultural investments have played an important role in the growth of the food supply through technological progress, and they will be crucial for achieving a sustainable food production in the future. [27]

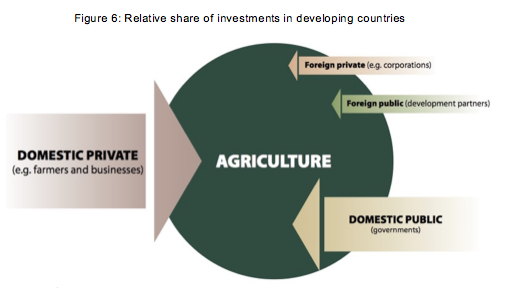

The majority of investments in agriculture are made by farmers, who purchase machinery, buy and/or raise animals, plant crops, improve their land, etc. The next largest source of investment are national governments, followed distantly by foreign private and public investors (see Figure 6). [28] Data made available by the FAO shows that in developing countries, investments by farmers are more than three times larger than the other sources of investment combined. [29]

Essentially, when farmers make investments, they give up certain things now (such as money and time) in order to build up capital that will allow them to become more productive in the future. As a result, these investments are a crucial determinant for agricultural productivity and production. [30]

A useful proxy for these private agricultural investments is the agricultural capital stock (ACS) per worker. In this sense, a higher rate of agricultural productivity can only be achieved through an increase in the amount of capital per worker. [31]

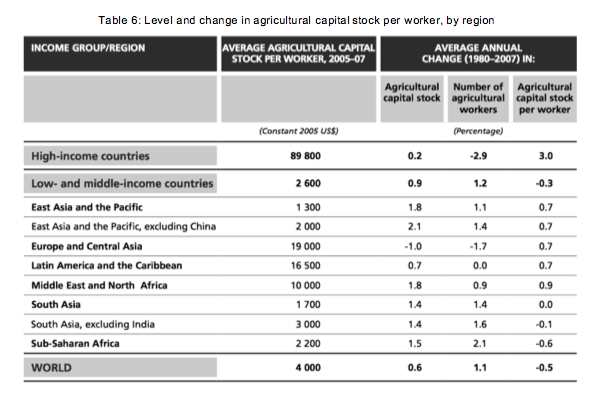

Yet according to the FAO, global ACS per worker has declined at an average annual rate of 0.5% in the last decades (from 1980 until 2007). This was caused by a slower growth in the agricultural capital stock (+ 0.6% per year) than the increase in agricultural workers worldwide (+ 1.1% per year) (See Table 6). [32]

In high-income countries, the ACS per worker has increased rapidly at an average annual rate of +3%. This was not the result of a rapid increase in capital investments (+ 0.2% per year), but rather due to a large decline in the number of workers in the sector (- 2.9%). On the other hand, the capital-labour ratio diminished at an annual rate of 0.3% in low- and middle-income countries. In particular, Sub Sahara Africa experienced declining capital levels per worker (- 0.6%) as a fast growth in its agricultural labour force outpaced its increases in agricultural capital stocks. Moreover, there was a stagnation of the capital-labour ratio in South Asia since the capital stock and labour force were rising at more or less the same rate. This indicates that investments have been stagnating in absolute terms in high-income countries, while they have declined in relative terms in the lower and middle-income countries, and especially in Sub Sahara Africa and Asia.

This suggests that investments have been in relative decline in the lower and middle-income countries, and especially in the regions with the highest rates of undernourishment today, Sub Sahara Africa and Asia. The amount of agricultural investments should be increased significantly in order to boost food production and to eradicate hunger in these regions in a sustainable way. [33]

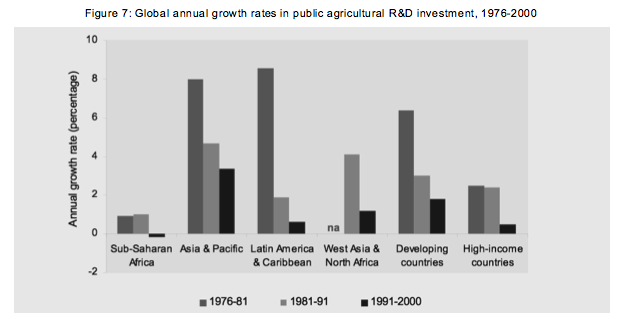

Moreover, not only has there been a small relative decrease in global private agricultural investments, but the worldwide growth in public spending on agricultural research and development (R&D) is also slowing down. As the figure below indicates, the annual growth rate in global public agricultural R&D spending has been diminishing steadily for the last four decades. In most of the regions of the world, this growth fell from rather high rates in the 1970s to significantly lower rates in 1991 to 2000, often close to zero. [34]

This is rather surprising, since many economic studies have concluded that agricultural R&D investments can have high economic and social returns, as they are able to increase productivity and reduce poverty over time. [35]

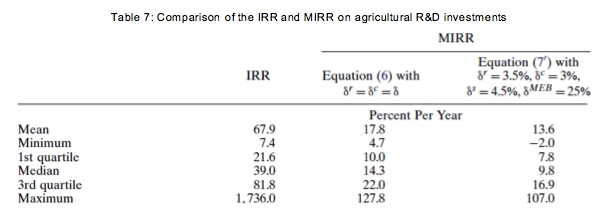

For instance, in 2014 Terrence Hurley and his colleagues conducted a meta-study in which they re-examined 2 242 investment evaluations made for different countries since 1958. They underlined that the internal rate of return (IRR) has been the predominant indicator to measure the returns on agricultural R&D investments, despite the fact that its methodology has been criticised by economists for decades.[36]

By using the modified internal rate of return (MIRR), which gives a more credible estimate on the annual interest rate paid by investments and corrects several methodological shortcomings of the IRR, they found an average annual return rate of 13.6% for agricultural R&D investments. [37]

If we look at this high return rate, it should be questioned why public agricultural R&D spending has been scaled back in many countries. The authors of this study state that if the growth rate in public spending continues to decline, the growth in agricultural supply will fail to meet growing food demand, which will put upward pressure on the food prices and further stress the world’s most vulnerable populations. [38]

To conclude, higher levels of investments by farmers and the public sector will be necessary to achieve global food security in a sustainable way. [39] Without these additional expenses, the production of food will probably not be able to keep up pace with a rising demand, especially in developing countries. [40]

Providing precise numbers of the necessary financial inputs to secure the global food supply is a difficult task. However, a set of reports made by the FAO estimated that, for developing countries alone, a net annual private investment of 83 billion dollars until 2050 would be necessary to strike a balance between the demand and supply for agricultural products. Additionally, the eradication of hunger by enhancing the resilience of the agricultural sector in these countries would require an extra public expenditure of 750 billion dollars in the next 15 years. [41]

Moreover, it should be noted that these figures do not even include the public and private investment needed to adapt to the effects of climate change and to achieve an environmental sustainable production system. Since it often takes a considerable amount of time before the impact of investments for agricultural productivity is fully realised, these expenditures need to be made soon in order to secure the global food supply by 2050. [42]

- Limiting factors for the balance between food demand and supply

Access to finance for small-scale farmers

Globally, around 500 million people can be categorised as small-scale farmers, since they possess not more than two hectares of arable land. As these smallholders constitute the vast majority of farmers in developing countries and feed a large part of the rural poor, global food security will continue to depend on their ability to supply agricultural products. [43]

However, small-scale farmers, and in particular those living in developing countries, face numerous challenges, such as low levels of productivity, restricted access to markets for their products, and especially the limited availability of finance. [44]

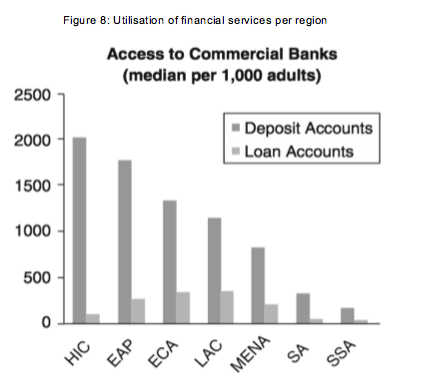

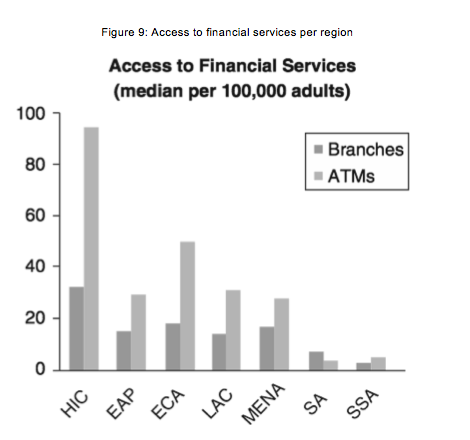

The two figures below, which are based on data provided by the World Bank, illustrate the limited access to finance of people living in developing countries. While these data represent the general access to finance across different regions and are therefore not specific to farmers and agriculture, they can nevertheless serve as a good indicator. They show that the presence of financial institutions and the utilisation of financial services is significantly lower in Sub Sahara Africa and South Asia, especially in comparison with high-income countries. [45]

Additionally, when farmers in developing countries do have the possibilities to lend money, they are often forced to do so at very high interest rates, since financial institutions face several risks in providing their services there. Furthermore, loans for agriculture are severely underrepresented in the lending activities of commercial banks in these regions. For example, while agriculture is a key economic activity in Africa, employing more than half of the population, only 1% of commercial lending is used for the agricultural sector. [46]

Improving the access to finance for small-scale agriculture in developing countries is therefore an important challenge for the future, since the lack of funds prevents farmers from investing in technologies which could make their production more efficient and could reduce the levels of hunger and poverty within these regions. Better financing possibilities for these farmers could also help them to adapt to the effects of climate change and increase the resilience of their agriculture, which would contribute to global food security in the long run. [47]

This raises important practical questions on how we should improve this access to finance in these regions. How can we mobilise investments in developing countries in order to build value chains to the benefit of rural economies and local farming? How can we make the contributions of private investors, public development aid and (pan-)regional investment banks compatible? And how should we promote good governance practices to ensure a stable investment environment in these countries?

Price fluctuations for agricultural commodities

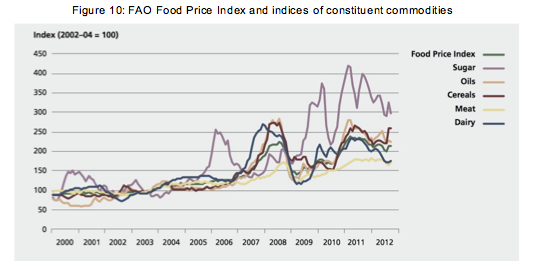

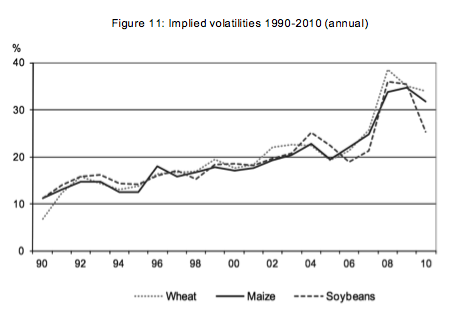

In the last two decades, food prices have been more volatile than in the preceding two decades, and these high fluctuations are likely to continue in the future. Indeed, as the graph below [48] shows, the prices of most agricultural commodities have been increasingly volatile in the last decade. [49]

Similarly, Figure 11 indicates that the implied volatility, which is a measure for the expected price volatility among market participants, has increased significantly for the major crops in this period. [50]

These large variations in prices have a number of negative consequences, as they create a high level of uncertainty among producers and consumers. Moreover, they are especially problematic for farmers and households in low income countries. Since food accounts for a large proportion of their income and budget, both the welfare of these households and the viability of their agricultural production can be threatened by excessive price volatility. On the one hand, producers are more concerned about the prospect of low prices, since a lower income may threaten their viability in the long term. On the other hand, the ability of poor households to ensure their nutrition and other basic needs (such as education and health care) can be compromised when food prices are high. [51]

Additionally, farmers are less willing to invest in productivity-raising assets when prices are unpredictable, and this may encourage them to take sub-optimal investment decisions in the long term. [52] [53] Periods of price depression are a major problem for farmers who have recently made investments, both in developing and developed countries, and these may prevent them from making the necessary contributions to tackle the global food security challenge.

It is likely that these high variations in agricultural prices will persist in the future, as they will be influenced by the changes in the demand and supply factors described in the previous chapters of this article. Additionally, climate change may result in worsening production conditions for the most vulnerable regions, which could lead to even higher levels of price volatility. [54] As these developments are likely to increase the frequency of future crises in the agricultural sector, policy responses should be initiated at the macro-level, and they will need to include tools to help stabilise agricultural revenues and install a favourable climate for sustainable investments.

Food waste and food loss

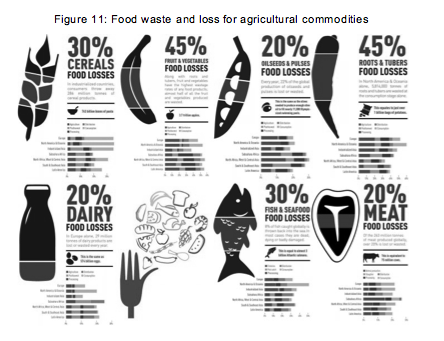

A final issue that affects the supply-demand balance is food wastage, which refers to the decrease in the amount of food throughout the food chain. The FAO makes a distinction between ‘food loss’, which occurs at the production and processing level, and ‘food waste’, which takes place at the final stages of the food chain, namely the retail and consumption level. Food waste and loss have various causes and occur in many ways, but the general outcome is a lower availability of food for all people. [55] [56]

In 2011, the FAO gave significant visibility to this issue by estimating that around one third of the food produced is lost or wasted worldwide, amounting to 1.3 billion tons per year. In terms of each commodity group, 20% of dairy products and meat, 30% of cereals, 30% of fish and almost half of fruit and vegetables are produced, but never consumed. [57]

While these rates are as high in industrialised countries as in developing countries, these two types of countries also differ in important ways. On the one hand, food losses occur more in developing countries: they mainly face post-harvest and production losses because of insufficient infrastructures, poor storage facilities and lower technological capacities. On the other hand, food waste mainly takes place within industrialised countries. In these parts of the world, restaurants, households and stores are primarily responsible for these losses, because of plate waste and throwing away food which is spoiled or does not meet aesthetic standards.

Nevertheless, in both types of countries food is wasted between the initial agricultural production and the final consumption. [58]

The magnitude of this problem should not be underestimated, and is it not only an ethical issue. It also leads to a major squandering of limited natural resources and needless greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to climate change and global warming. This means that eliminating waste could significantly reduce the existing pressures on the earth’s resources, such as land, water, and soil. [59]

Moreover, it is an obstacle for global food security. If food wastage can be reduced, a smaller increase in production would be needed to meet the rising demand in the next decades. For example, if we would reduce half of the food wastage by 2050, agricultural production would only need to rise with 25 percent by 2050, instead of the 50% estimated by the FAO. [60]

In short, reducing food waste and food loss could help to improve food security and diminish the pressure on the environment. In this respect, there is a shared responsibility for the actors who produce and process the food (such as farmers and food processors), those who make them ready for consumption (such as the retail sector), and finally the consumers themselves.

Surmounting the challenge of food losses and food waste will require significant investments in infrastructure, as well as increased agricultural know-how in developing countries and major changes in consumer behaviour in developed countries. Even so, the question remains how we can determine realistic targets for the reduction of food wastage which could help us to address the food challenges in the near future.

- Conclusion

This article examined some of the dimensions that will determine the ability of agriculture to respond to the future demand for food. It should be highlighted that this overview is not exhaustive, as several relevant aspects (such as biofuels) have been excluded from the analysis. Nevertheless, it aims to provide enough elements to stimulate a discussion on how the demand and supply factors for food may evolve in the next decades.

This study began by observing that the two major drivers of future food demand, namely a growing population and changing consumption patterns, will significantly increase the demand for food in the coming decades. This will require a substantial additional production of agricultural commodities, as the global supply of food will have to increase by almost 30% by 2030 and by around 50% by 2050 if it wants to meet the rise in global demand.

Since the possibilities for further increases in farmland appear to be rather limited, expanding the food production will largely depend on our ability to maintain or increase the current levels of agricultural productivity. This proves to be a difficult task, as historical growth rates in productivity have been lower than the expected productivity rise in the future. Moreover, it is unlikely that this productivity growth can be achieved if private investments keep declining relatively and public spending on agricultural R&D continues to slow down worldwide.

Additionally, some elements have been highlighted that could further hinder the balance between food demand and supply. As small-scale farmers have limited access to finance, fluctuations in agricultural prices remain high, and the amount of food wasted and lost is substantial, tackling these obstacles will determine our ability to realise global food security.

This raises the question of how Europe can take its responsibility and shape the outcomes of these global evolutions. The findings of this article suggest that it should not act as a helpless bystander, but rather play the role of an active participant by promoting public and private investments in agriculture, taking policy measures to manage price volatility, and increasing its efforts to reduce global food waste.

Furthermore, we should also consider how we can produce enough food for more than seven billion people without putting unsustainable pressures on our planet. A significant growth in the supply of agricultural products should be realised, but this will put increasing strains on our natural resources, which are already severely degraded. This issue becomes even more compelling if we take into account the effects of climate change on food production, such as higher temperatures, more variable weather conditions, and a higher occurrence of floods and droughts.

Meanwhile, as the regions most vulnerable to the impact of climate change continue to have the highest levels of undernourishment and are expected to have the largest increase in population growth, ensuring the food supply should also involve efforts to eradicate hunger in these parts of the world. While this does not mean that we are expecting a Malthusian catastrophe to occur in the next decades, it underlines how important it will be for agriculture to meet these daunting challenges.

References

Alexandratos, N. and Bruinsma, J. ‘World Agriculture Towards 2030/50: The 2012 Revision.’, ESA Working Paper, No. 12-03, 2012.

Bagherzadeh, Inamura, M. and Jeong, H. ‘Food Waste Along the Food Chain’, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 71, 2014.

Beintema, N. and Elliott, H. Setting meaningful investment targets in agricultural R&D: Challenges, opportunities, and fiscal realities, 2009.

BIPE and Avril, The Oil and Protein Sectors as a Solution for Meeting Global Challenges in 2030, December 2014

Conforti, P. ‘Looking ahead in World Food and Agriculture’, FAO Report, 2011.

European Commission, Food Waste,

http://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/index_en.htm.

European Parliament, Options for Sustainable Food and Agriculture in the EU, November 2013.

FAO, Food and Nutrition in Numbers, 2014.

FAO, Global agriculture towards 2050, 2009.

FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011.

FAO, Save Food: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction, http://www.fao.org/save-food/resources/keyfindings/infographics/fish/en.

FAO, The state of food and agriculture: investing in agriculture for a better future, 2013.

Fuglie, K. ‘Total factor productivity in the global agricultural economy: Evidence from FAO data’, in J. Alston, B. Babcock and P. Parday (Eds.), The Shifting Patterns of Agricultural Production and Productivity Worldwide, Ames, Midwest Agribusiness Trade and Research Information Center, Iowa.

Gardner, B. Global Food Futures: Feeding the World in 2050, London, Bloomsbury, 2013.

Hofstrand, D. ‘Can we meet the world’s growing demand for food?’, AgMRC Renewable Energy & Climate Change Newsletter, February 2014.

Hofstrand, D. ‘More on feeding nine billion people by 2050’, AgMRC Renewable Energy & Climate Change Newsletter, January 2012.

Hurley, T. et al., ‘Re-examining the reported rates of return to food and agricultural research and development’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 96, No. 5, 2014, pp. 1312-1323.

International Finance Corporation, Access to Finance for Smallholder Farmers: Learning from the Experiences of Microfinance Institutions in Latin America, 2014.

Keating, B. et al., ‘Food wedges: Framing the global food demand and supply challenge towards 2050’, Global Food Security, Vol. 3, No. 3-1, p. pp. 125-132.

Maggio, N. et al. Global Food Security 2030: Assessing trends with a view to guiding future EU policies, 2015.

Matthews, A. What is happening to EU agricultural productivity growth, 4 May 2014.

Pardey P. et al., Investments in and the Economic Returns to Agricultural and Food R&D Worldwide, Academic Press, New York, 2014.

Rosegrant, M. ‘Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies’, Science, Vol. 302, No. 5652, 2003, pp. 1917-1919.

The Telegraph, Gloomy Malthus provides food for thought as world’s appetite builds, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/liamhalligan/8363500/Gloomy-Malthus-provides-food-for-thought-as-worlds-appetite-builds.html.

United Nations, World Population Prospects: the 2015 Revision, New York, United Nations, 2015.

World Bank, ICT in Agriculture: Connecting Smallholders to Knowledge, Networks, and Institutions, November 2011.

[1] The Telegraph, Gloomy Malthus provides food for thought as world’s appetite builds, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/liamhalligan/8363500/Gloomy-Malthus-provides-food-for-thought-as-worlds-appetite-builds.html.

[2] M. Rosegrant, ‘Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies’, Science, Vol. 302, No. 5652, 2003, p. 1917.

[3] P. Conforti, ‘Looking ahead in World Food and Agriculture’, FAO Report, 2011, pp. 1-2.

[4] United Nations, World Population Prospects: the 2015 Revision, New York, United Nations, 2015, p. 2.

[5] Ibid.

[6] B. Gardner, Global Food Futures: Feeding the World in 2050, London, Bloomsbury, 2013, p. 7.

[7] Rosegrant, loc. cit.

[8] D. Hofstrand, ‘Can we meet the world’s growing demand for food?’, AgMRC Renewable Energy & Climate Change Newsletter, February 2014.

[9] FAO, Global agriculture towards 2050, 2009, p. 1.

[10] D. Hofstrand ‘More on feeding nine billion people by 2050’, AgMRC Renewable Energy & Climate Change Newsletter, January 2012.

[11] Gardner, op. cit., p. 4.

[12] BIPE and Avril, The Oil and Protein Sectors as a Solution for Meeting Global Challenges in 2030, December 2014, pp. 6-7.

[13] Gardner, op. cit., p. 68.

[14] A. Maggio et al., Global Food Security 2030: Assessing trends with a view to guiding future EU policies, 2015, p. 9.

[15] N. Alexandratos and J. Bruinsma, ‘World Agriculture Towards 2030/50: The 2012 Revision.’, ESA Working Paper, No. 12-03, 2012, p. 7.

[16] B. Keating et al., ‘Food wedges: Framing the global food demand and supply challenge towards 2050’, Global Food Security, Vol. 3, No. 3-1, p. 128.

[17] BIPE and Avril, op. cit., p. 14.

[18] Alexandratos and Bruinsma, loc. cit.

[19] Maggio et al., op. cit., p. 6.

[20] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, p. 11.

[21] European Parliament, Options for Sustainable Food and Agriculture in the EU, November 2013.

[22] Hofstrand, 2012, loc. cit.

[23] K. Fuglie, ‘Total factor productivity in the global agricultural economy: Evidence from FAO data’, in J. Alston, B. Babcock and P. Parday (Eds.), The Shifting Patterns of Agricultural Production and Productivity Worldwide, Ames, Midwest Agribusiness Trade and Research Information Center, Iowa, pp. 85-89.

[24] BIPE and Avril, op. cit., p. 16.

[25] FAO, op. cit., p. 2.

[26] A. Matthews, What is happening to EU agricultural productivity growth, 4 May 2014.

[27] P. Pardey et al., Investments in and the Economic Returns to Agricultural and Food R&D Worldwide, Academic Press, New York, 2014, p. 79.

[28] FAO, The state of food and agriculture: investing in agriculture for a better future, 2013, p. 9.

[29] FAO, op. cit., p. 11.

[30] Pardey et al., op. cit., p. 95.

[31] FAO, op. cit., p. 15.

[32] FAO, op. cit., p. 18.

[33] FAO, op. cit., p. 19.

[34] N. Beintema and H. Elliott, Setting meaningful investment targets in agricultural R&D: Challenges, opportunities, and fiscal realities, 2009, p. 7.

[35] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, p. 16.

[36] T. Hurley et al., ‘Re-examining the reported rates of return to food and agricultural research and development’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 96, No. 5, 2014, pp. 2-3.

[37] Hurley, op. cit., pp. 4-12.

[38] Ibid., p. 12.

[39] FAO, The state of food and agriculture: investing in agriculture for a better future, 2013, pp. 36-37.

[40] Gardner, op. cit., p. 13.

[41] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, p. 16.

[42] Pardey, op. cit, p. 79.

[43] International Finance Corporation, Access to Finance for Smallholder Farmers: Learning from the Experiences of Microfinance Institutions in Latin America, 2014, p. 5.

[44] Ibid.

[45] World Bank, ICT in Agriculture: Connecting Smallholders to Knowledge, Networks,

and Institutions, November 2011, p. 153.

[46] World Bank, op. cit., pp. 152-153.

[47] International Finance Corporation, Ibid., p. 1.

[48] FAO, The state of food and agriculture: investing in agriculture for a better future, 2013, p. 99.

[49] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, pp.7-9.

[50] Ibid., p. 8.

[51] Ibid., p. 6.

[52] FAO, Food and Nutrition in Numbers, 2014, p. 8.

[53] Hofstrand, 2014, op. cit.

[54] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, p. 11.

[55] FAO, Food Loss and Food Waste, http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en.

[56] European Commission, Food Waste, http://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/index_en.htm.

[57] FAO, Save Food: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction, http://www.fao.org/save-food/resources/keyfindings/infographics/fish/en.

[58] FAO, Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, 2 June 2011, p. 28.

[59] M. Bagherzadeh, M. Inamura and H. Jeong, ‘Food Waste Along the Food Chain’, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 71, 2014, p. 6.

[60] Hofstrand, 2012, op. cit.