SUMMARY

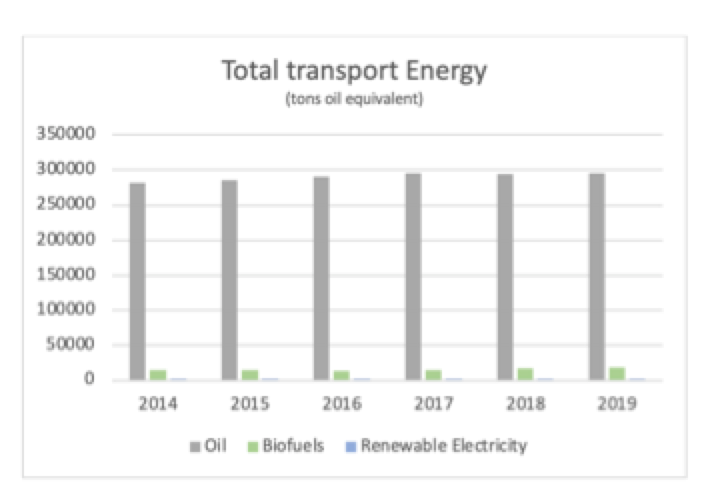

Demand for energy in transport rose 7% overall during the five years to 2020.

Oil maintains an overwhelming grip on the sector with a steady 94% share. The rest is biofuels with 5.6% and renewable electricity with 0.6%. Three quarters of the extra energy demand over the period was met by oil. 98% of renewables growth was biofuels.

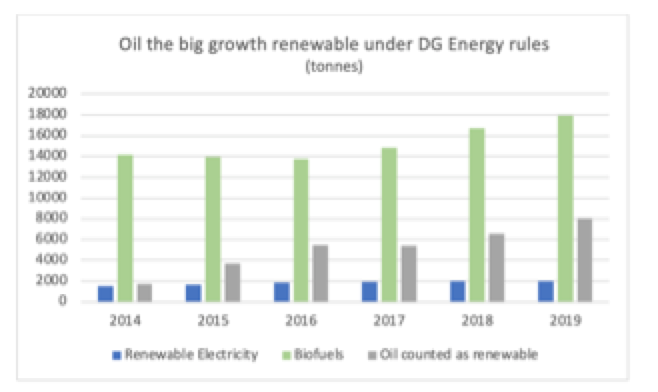

While the Commission highlights a figure of 8.88% for renewables in transport energy in 2019 this is not a true amount, including as it does, about 8.2 million tonnes of fossil fuel classed as renewables under the multipliers loophole of the Renewable Energy Directive. The true renewables figure was a more modest 6.3%.

Thus a sizeable portion of what is reported as renewables in transport energy consumption, and actually consumed, is in fact oil. From a reporting perspective it is vital that the Commission ceases to include oil in its headline figures for transport renewables as they have a grossly distorting effect.

In the interest of fraud prevention and better policy making it should report countries of origin of biofuels, especially for used cooking oil. It should report biomass types and origins of crop biofuels, especially in the case of palm oil, and it should report biomass types and origins for advanced biofuels in order to allow policy makers track and modulate the effects of their regulation.

Even with 8 million tonnes of oil counted as renewable, and a million or two tonnes of palm oil labelled as UCO it emerges from the data that growth in overall transport energy has run at twice the pace of growth in renewables over the last five years. Remove the dodgy oil and fossil energy growth beats renewables by a factor of three to one over the period.

For 2030 the European Commission has indicated a target of 24% renewables for the transport sector, and a similar level of cuts in carbon emissions. Yet it is difficult to see how the current trends can be so radically changed. Massive schemes will need to be put in place to support the deployment of renewable electricity. Palm oil biodiesel and UCO fraud will need to be brought under control. Multipliers should be eliminated as they simply represent another form of climate action indulgence, while completely distorting member state policies and behaviours. The European Tax Directive reforms of 2015 should be voted through, and soon. Biogas – the sleeping beauty of European renewables – needs to expand dramatically.

The EU needs to further the contribution of sustainable European biofuels, which could easily double by 2030. Positive policies should be put in place to allow that happen. If anything should be capped it is oil consumption, not sustainable European biofuels.

ANALYSIS

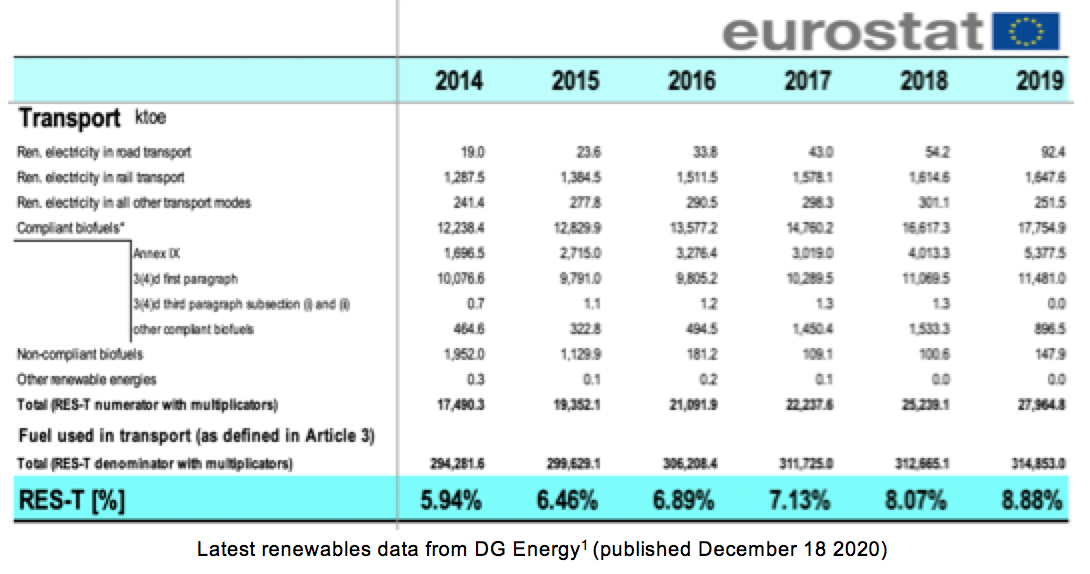

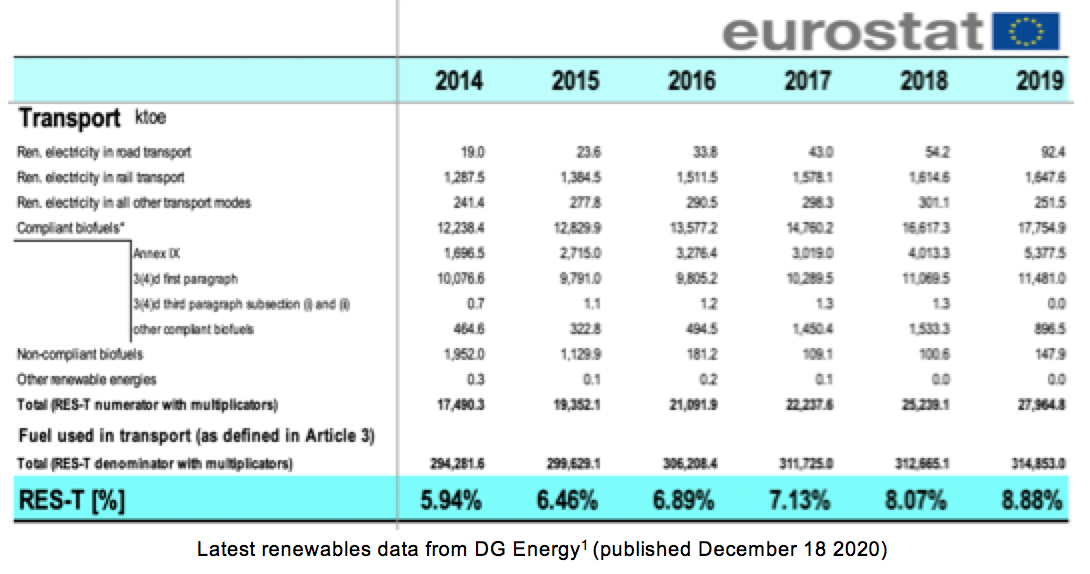

In December 2020 the European Commission published its latest data[i] for transport energy and renewables in Europe, as reported to it by member states for 2019 under the Renewable Energy Directive. Farm Europe reviewed the data and presents its findings here.

Steady rise in transport energy demand, half of it renewable

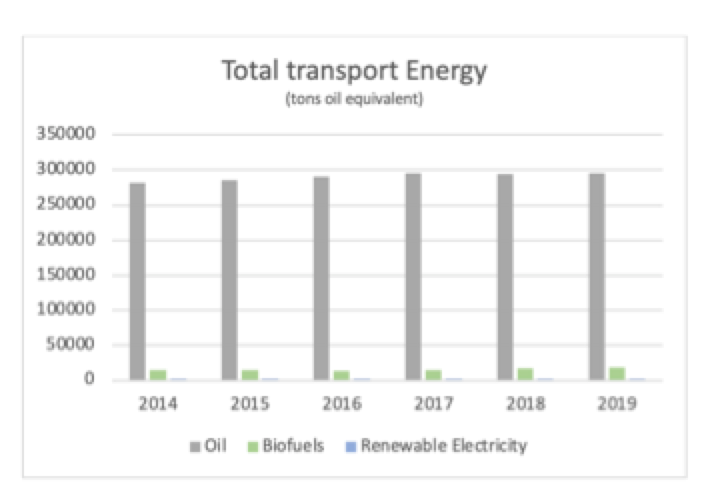

Demand for energy in transport rose 7% overall during the five years to 2020 according to the EUROSTAT data, with a near 1% increase in 2019. Vehicle numbers grew at a similar rate[i] with the EU fleet size expanding by around three million cars and trucks annually.

Oil maintains an overwhelming grip on the sector with a steady 94% share. The remainder was comprised of biofuels with 5.6% and renewable electricity with 0.6%. Three quarters of the extra energy demand over the period was met by oil. The trend towards renewables is improving somewhat: In 2019 the portion of additional energy demand supplied by oil was down to 45% with the remainder coming from additional renewable energy. Virtually all (>98%) of the additional renewable energy in 2019 was additional biofuels, with renewable electricity contributing the balance.

Oil treated as renewable, under RED multiplier rules

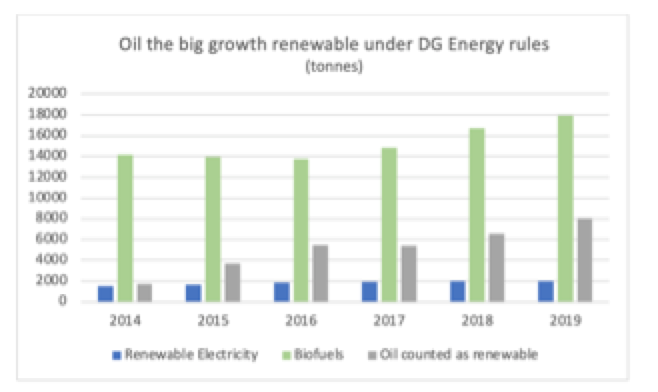

Under the RED method of adding up renewables in transport substantial amounts of fossil fuel enter the figures, creating some distortion in the reporting. So while the Commission highlights a figure of 8.88% for renewables in transport energy in 2019 this is not a true amount, including as it does, about 8.2 million tonnes of oil classed as renewable under the multiplicators loophole of the directive. The true renewables figure was a more modest 6.3%.

The multiplicators provision allows some renewables to be counted two or more times their actual values, when adding up the total, as an incentive for their development. It is not actual consumption of renewables that is reported.

The distortion is intensifying year on year, with fossil oil accounting for nearly 30% of the Commission’s reported renewables in 2019, up from 19% five years ago. Indeed there was bigger growth in oil classed as renewable by the Commission in 2019 than there was growth in actual renewable energy in the period. Oil labelled as renewable by DG Energy grew 70 times faster than genuine renewable electricity for instance.

Some countries lean on the practice more than others. In the UK for example, fossil oil accounted for 45% of the renewable energy in transport that it reported under Brussels rules for 2019. The country increased its consumption of multiple-counted used cooking oil biodiesel by 55% compared to the previous year. For every one of the 1.1 billion litres of UCO the UK put into its diesel, it declared a matching litre of fossil fuel as renewable.

Is Used Cooking Oil expansion legitimate?

Used cooking oil biodiesel (UCO) is by far the biggest example of multiple counted energy, and far from being a niche player it has become a dominating element on the distortive effects of multipliers.

Used cooking oil biodiesel grew 35% last year across the EU28 according to the data, and averaged 44% annual growth since 2014. Consumption reached 4.1 billion litres in 2019, up from 517 million in 2014. While the UK, Germany and the Netherlands accounted for two thirds of total UCO demand in 2019, France, Ireland, Portugal and Spain accounted for another 20% between them. Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands were the biggest per capita consumers of UCO diesel in 2019, with Ireland at 38 litres per person and Luxembourg at 60. These are large numbers if one considers that a country with a mature UCO collecting infrastructure will collect at most 4 or 5 litres per annum domestically while most countries in the world collect one litre or less per person, or quite commonly, none at all.

The majority of EU member states sought big increases in UCO utilisation last year, with the UK, Sweden, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Netherlands, Hungary, France, Czechia and Croatia all participating in rapid expansion. Only Germany bucked the trend, with a 23% drop in UCO consumption.

The total amount of UCO consumed in EU biodiesel in 2019 was four times what is collected domestically from Europe’s catering sector. Hence the bulk of it is imported from jurisdictions where Europe has no powers to investigate or prosecute operators tempted into the fraudulent substitution of UCO with lower cost and readily available bulk palm oil. DG Energy allows any biodiesel declared as UCO to be counted as UCO under the directive, without requiring physical audits or inspections of the supply chains and without any form of supply chain risk assessment. UCO fraud is financially rewarding, easy to get into and largely free of interference by governing bodies. UCO fraud represents a major lost opportunity to Europe’s farm sector, which produces highly sustainable and effective biofuels and would have the capacity to produce more under a smart and fair regulatory system.

DG Energy does not[i] publish country of origin data for the UCO consumed as biofuel under the renewable energy directive. However that data is provided to them by law so could be published, and it would be of great interest if it was. It would allow stakeholders identify and assess situations involving countries listed as sources of UCO in quantities that are greater then their UCO collection infrastructure would allow in reality.

To take one example, Malaysia, in addition to being the world’s second largest producer of palm oil, is an important supplier of UCO to Europe’s biodiesel industry. The UK and Ireland – in contrast with DG Energy – do publish[i] the countries of origin of the biofuels they consume. Malaysia was the origin of 90 million litres of the UCO used in Britain and Ireland in 2019. If Malaysia is the origin of similar volumes for the rest of Europe then its total contribution to EU UCO demand amounts to six or eight times its capacity for genuine UCO collection. The implications are clear: under weak regulation the UCO gold rush is likely as much about palm oil as genuine UCO, with British, Irish and other EU consumers unwittingly burning palm oil in their diesel vehicles instead of genuine waste cooking oil.

Advanced biofuels

The volume of advanced biofuels in the renewables mix rose about 17% in 2019 to just over a million tonnes of oil equivalent, contributing 0.3% of Europe’s transport energy and 5.3% of renewable energy in the sector. Growth in advanced biofuels in 2019 was about seven times greater in absolute terms than growth in renewable electricity but it was three times lower than crop biofuels growth, five times lower than UCO, and eight times lower than the fossil oil counted as renewable by DG Energy under the multiplicators loophole.

Advanced biofuels are made from materials contained in a list compiled by DG Energy – loosely intended as residues and co-products from industry and agriculture – and have for the last decade been strongly promoted by DG Energy. In addition to being double-counted like UCO, there is an obligation on member states to raise consumption to 1.75% of their transport energy needs by 2030, or about six times current average rates. DG Energy has also provided around half a billion euros in grant aid to the sector in the last decade, in particular for the production of biofuels from materials such as straw, with limited results showing up in the Eurostat data thus far.

Over 90% of advanced biofuels are consumed in just five member states: Finland (36%), Sweden (23%), UK (21%), the Netherlands (8%) and France (4%). Indeed most member states use little or no advanced biofuels, making their targets for 2030 quite challenging.

All of the 2019 increase of 150 thousand tonnes was attributable to Finland (45%), the Netherlands (30%), and Sweden 15%), with small rises seen also in France and Germany. Virtually all advanced biofuels in Europe come from just two of the seventeen types allowed in the directive: Industrial waste and forestry waste, with the industrial waste accounting for over 80% of it. Industrial waste is a broad category and it would be helpful for policy makers if DG Energy were to report more precisely what raw materials and source countries are involved.

Some stakeholders are concerned that without reform of the Commission’s regulatory competencies and procedures, the opportunities and incentives for fraud seen in UCO are transfering to advanced biofuels as the sector grows, with operators tempted to game the system both outside and inside Europe.

Crop biofuels

Crop biofuels are by far the largest category of renewables in the EU transport system, according to the data, accounting for a steady 3.5% of total transport energy over the past five years, and for around 60% of all renewable energy. In volume terms crop biofuels expanded 3% annually over the five year period, to reach 11.5 million tonnes of oil equivalent in 2019. The low growth in crop biofuels is attributable to the Commission’s decision to limit their role in renewable energy even though, in the case of domestically sourced crop biofuels, they are demonstrably better for the climate than increased use of oil, represent the lowest cost means of carbon emissions abatement and could be expanded with considerable benefits for Europe’s rural economy and food sector.

For such an important contributor to climate action in transport, to rural economic development and to protein feed security there is little detail in the data released by the Commission. There is no breakdown in the data to distinguish between domestically produced bioenergy and imports, or between the various types of biomass used.

Critically, the Commission omits to provide data on diesel made from palm oil, which it continues to allow under the legislation despite the environmental harm and carbon emissions associated with palm oil expansion. In fact the Commission allows low cost palm oil compete directly with highly sustainable domestically sourced crop biofuels from traceable European agriculture. This lack of feedstock and source country data is a grave omission as it obscures the situation, preventing policy makers from making accurate assessments.

Biogas in transport

Just 1.6% of renewable bioenergy in the EU transport system in 2019 was contributed by biogas, coming to 279 thousand tonnes of oil equivalent, or 0.1% of all transport energy. Biogas development, though coming from a low base, was positive, with around a 45% annual increase over the five year period. According to the data, the seven countries involved were Sweden (39%), the UK (27%), Germany (20%) and the Netherlands (7%), with Denmark, Estonia and Finland accounting for another 6% between them in 2019. In the case of the Netherlands all of its transport biogas was delivered through the natural gas grid, whereas in the other six countries it was directly fuelled. Italy also uses biogas in its transport system, and has enacted major legislation to support biogas in transport, but has not yet provided consumption data for EUROSTAT.

Biogas is seen by many energy experts as a highly effective means for enlarging the share of advanced biofuels, and of bioenergy and renewables generally. It can be readily produced from virtually any type of biomass and it can be consumed directly as heat and power, distributed through the existing natural gas grid or converted to electricity and distributed through the electricity grid. For a major scale-up to happen however one would need a common EU certification scheme, alignment of national support schemes for production and consumption and barrier-free cross-border access to those schemes. The current patchwork of incompatible national systems is a great barrier to sector development.

Electric cars

Renewable electricity in road transport in 2019 accounted for 0.03% of transport energy. This is up from 0.01% five years ago, but is still a low base and far from being a significant contributor to the 10% renewables target for 2020. In volume terms in 2019 renewable electricity on the road grew by the equivalent of 38 thousand tonnes of oil or enough to displace the fossil energy of about a hundred thousand conventional cars. The total EU28 fleet grew by 30 times that number – about 3 million vehicles – in the same period, indicating that renewable electricity has a way to go yet, to impact the trend in fossil energy consumption in the sector.

Overall, renewable electricity in transport, including rail, has hovered around 0.6% of total transport energy over the five year period to 2020.

The data shows that renewable hydrogen and synthetic fuels have yet to make a contribution to the energy mix.

Outlook for 2030

From a reporting perspective it is vital that the Commission ceases to include oil in its headline figures for transport renewables as it has a highly distorting effect. In the interest of fraud prevention and better policy making it should report countries of origin of biofuels, especially for used cooking oil. It should report biomass types and origins of crop biofuels, especially in the case of palm oil, and it should report biomass types and origins for advanced biofuels in order to allow policy makers track and modulate the effects of their regulation. The data should be released within three months of the end of the reporting period, and not a year later as is the current practice. Indeed the data should be released in quarterly cycles as done in the UK.

Even with 8 million tonnes of oil counted as renewable, and a million or two tonnes of palm oil potentially labelled as UCO it emerges from the data that growth in overall transport energy has run at twice the pace of growth in renewables over the last five years. Remove the inappropriate fossil fuel and fossil energy growth beats renewables by a factor of three to one over the period.

To nudge things in the right direction in 2021 oil consumption, which is currently subject to no limits, should be capped, and ideally its share of transport energy should be cut by some obligatory portion each year, even if only a percent or two.

For 2030 the European Commission has indicated a target of 24% renewables for the transport sector, and a similar level of cuts in carbon emissions. Yet it is difficult to see how the current trends can be so radically changed. Massive schemes will need to be put in place to support the deployment of renewable electricity. Palm oil biodiesel and UCO fraud will need to be brought under control. Multiplicators should be eliminated as they simply represent another form of climate action indulgence, while distorting member state policies and behaviours. The European Tax Directive reforms of 2015 should be voted through, and soon. Biogas – the sleeping beauty of European renewables – needs to expand dramatically. And in order to further the contribution of sustainable European biofuels, which could easily double by 2030, there should be positive policies put in place to allow that happen.

—- Analysis by James Cogan for Farm Europe.

References, endnotes

[i] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/energy/data/shares

[i] https://www.acea.be/statistics/article/size-distribution-of-the-vehicle-fleet

[i] https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/case/en/57742

[i]https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/renewable-fuel-statistics-2019-final-report; www.nora.ie/