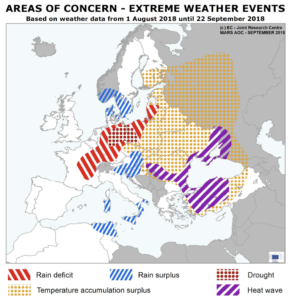

This summer recorded very high temperatures, which caused droughts that affected agricultural production heavily (e.g. arable crops and animal feed) in many EU countries. At the request of many Member States, the European Commission has activated a number of measures and derogations. Nevertheless, depending on where they are located on the EU territory, European farmers have faced more or less support from the national public authorities, each managing the crisis depending, of course, on its intensity, but, also and above all, depending on its financial capacity, exposing each farmer to significant disparities in treatment. Fresh money have been provided by 3 Member states : Germany (€ 340 millions), Sweden (€ 116 millions) and Poland (around € 116 millions).

This summer recorded very high temperatures, which caused droughts that affected agricultural production heavily (e.g. arable crops and animal feed) in many EU countries. At the request of many Member States, the European Commission has activated a number of measures and derogations. Nevertheless, depending on where they are located on the EU territory, European farmers have faced more or less support from the national public authorities, each managing the crisis depending, of course, on its intensity, but, also and above all, depending on its financial capacity, exposing each farmer to significant disparities in treatment. Fresh money have been provided by 3 Member states : Germany (€ 340 millions), Sweden (€ 116 millions) and Poland (around € 116 millions).

The Commission initially (beginning of August) made available various instruments, such as:

- higher advanced payments: farmers received up to 70% (up from 50%) of their direct payment and 85% (up from 75%) of payments under rural development already as of mid-October 2018 instead of waiting until December; (This decision is in the process of being adopted and is expected to be finalised later in the month. Payments will start from 16 October).

- derogations from specific greening requirements: crop diversification and ecological focus area rules on land lying fallow, in a view to allow this land to be used for the production of animal feed (to counteract the shortage in feed quantities due to weather conditions). In addition to this, other derogations on catch crops and green cover were considered by the Executive.

While considering the instruments for support already available under the existing Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) legislation, here below a brief overview:

- Under agricultural state aid rules: aid of up to 80% of the damage caused by drought (or up to 90% in Areas of Natural Constraint) can be provided, subject to certain specific conditions. In addition, the purchase of fodder can qualify for aid as either material damage or income loss. Compensation for damage can also be granted without the need to notify the Commission (the so-called “de minimis aid”). Member States may grant aid of up to €15 000 per farmer over three years.

- Under Rural Development:

- a Member State which recognises the drought situation as a natural disaster, could provide support of up to 100% for the restoration of agricultural production potential damaged by the drought. It has been specified by the EC that this support can be used for investments (i.g. re-seeding of pastures). This measure can also be activated retroactively;

- Farmers can notify their respective national authorities about cases of exceptional circumstances, and may be released by their Member State from their commitments under various schemes. For example, farmers will be allowed to use buffer strips for fodder (in this case no penalties apply);

- Risk management instruments can be used, as for instance as a financial contribution to mutual funds to pay financial compensation to affected farmers. Also, farmers who experienced an income loss beyond 30% of their average annual income received a financial compensation (a general IST).

Derogations from specific greening requirements were requested and voted on 12 July for 8 member states: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and Sweden.

On August 30, additional practical support (new measures) was announced by the Commission. Specifically, more flexibility was offered to help livestock farmers to provide enough feed for animals.

New package of derogations on greening rules, which were voted and formally adopted (on 19 September) include:

- “Possibility to consider winter crops which are normally sown in autumn for harvesting/grazing as catch crops (prohibited under current rules) if intended for grazing/fodder production;

- Possibility to sow catch crops as pure crops (and not a mixture of crops as currently prescribed) if intended for grazing/fodder production;

- Possibility to shorten the 8-weeks minimum period for catch crops to allow arable farmers to sow their winter crops in a timely manner after their catch crops;

- Extension of the previously adopted derogation to cut/graze fallow land to France”.

It is relevant to note that, these decisions, as the previous ones adopted beginning of August, apply retroactively.

Member that required derogations:

- On land lying fallow: Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Finland and Sweden;

- On catch crops and winter crops: Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, France, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden and the United Kingdom in respect of England and Scotland.

EU Member States have also adopted specific actions at national level.

National schemes: Approach & Measures

Germany

German farmers started to ask for federal help since from the beginning of August. However, German Agriculture Minister Julia Klöckner took time by saying that she was waiting for valid data (and not individual estimates) about the impact of this summer’s drought.

The DBV (the German Farmers Association) estimated a decrease in harvest of around 8 million tonnes of grains (18% of annual yield) calling therefore for financial support for German farmers. The organisation formally requested €1 billion to compensate farmers whose crops had been most severely affected.

It has to be noted that in Germany, the individual states are the ones responsible for aid measures in the case of extreme weather events.

On 15 August, the federal government in Berlin passed a motion which allowed German drought-hit farmers to grow animal feed in ecological focus areas (EFAs). Farmers were therefore enabled to grow a mixture of crops for feed purposes on EFAs.

Finally, on 22 August, when valid data showed that the extreme weather conditions caused a massive harvest loss in Germany, the federal government agreed to provide financial assistance – €170 million to offset business losses.

Federal aid (of €170 million) was added to the aid provided at state-aid level. Thus, about €340 million in emergency government measures (launched as a “special aid programme”) were provided for the most severely affected farmers.

(Specifically, the general threshold for government assistance in a weather crisis – state aid measure – is when a business loses more than 30 percent of its annual production).

The Federal government specified that the latest data showed damages for a total amount of €680 million, with around 10,000 farms, or one out of 25 farm.

Recent and updated DBV estimates, show that this year’s grain harvest is 26 percent lower than the annual crop yield from the previous five years. Furthermore, DBV President Joachim Rukwied specified that “8 of the 16 German federal states had already suffered financial damage of around €3 billion as a result of the drought” and that ”Many farmers in particularly badly affected regions in Germany’s north and east have reported harvest losses ranging from 50 percent all the way up to 80 percent or higher”.

State-aid level measures adopted

- Since from the beginning of August, drought-hit farmers in Germany could receive discounted loans from the Landwirtschaftliche Rentenbank;

- Federal states also examined tax relief measures;

- The state of Brandenburg provided 5 million euros in emergency aid (given mainly to animal owners to secure food supply and avoid slaughterings);

- Insurances against drought damage: GDV (the German insurance company) estimated that drought would cause damage of around 2 billion euros. Only few farmers in Germany are insured against drought (only about 5000 hectares against are insured against drought damage, since it does not occur very frequently as hail for instance and premiums and deductibles are quite high).

Other possibilities of assistance in the case of drought (beyond federal one)

- Rentenbank opened its liquidity protection program for companies in agriculture, horticulture and viticulture, which suffered losses of income or increased costs due to drought and thunderstorms in 2018;

- From 1 July 2018, countries can allow exceptionally, fallow land declared as ecological focus areas which may be harvested for fodder purposes if insufficient fodder is available;

- Bodenverwertungs-und-verwaltungs GmbH granted leases to drought affected farms;

- The BMEL has launched a draft regulation that allows farmers to use ecological focus areas for the cultivation of catch crops for fodder purposes;

- The following measures could be additionally taken: the damaged farms can make applications for deferment of tax debts. The damaged enterprises can defer the Sozia Apply for insurance contributions.The tax authorities of the federal states can adjust tax prepayments and waive default payments, deferred interest and enforcement measures.

France

At the end of July, France asked the European Union for an advance on direct aid and rural development aid.

At the national level, the tax relief on underdeveloped land (TFNB) for plots affected by drought, as well as the deferral of payment of social security contributions to the funds of the Mutualité sociale agricole (MSA) were adopted. Hay transport aids in grazing areas might be considered.

Ireland

In Ireland, a fodder support scheme was introduced for livestock farmers first in Spring 2018.

A total amount of €1.5m scheme was earmarked to cover fodder transport costs.

On 22 August an additional amount of €4.25 million was allocated by the Irish government for a new Fodder Import Support measure, which aimed at reducing the cost of imported forage for drought-hit farmers in an already complex fodder situation. The Irish government specified that the measure would be operated through the co-ops and registered importers, and that it would cover forage imported from 12th August 2018 to 31st December 2018 (measure regulated under EU State Aid de-minimis rules).

The following support measures were introduced by the Irish government previously (Commission’s formal approval procedure still ongoing for some of them):

- “advance payments of EU aid under Pillar 1 and 2, amounting to nearly €260 million of additional cash flow;

- additional flexibilities to certain GLAS (Green, Low-carbon, Agri-environment Scheme) measures to increase fodder production;

- the allocation of €2.75 million to a Fodder Production Incentive measure for tillage farmers and an extension to the period for spreading chemical and organic fertilisers to allow farmers avail of late season grass growth”.

Furthermore, to cope with the problematic situation, the dairy cooperative Kerry Agribusiness, gathering 3,250 farmers on the island of Emerald, launched a feed assistance program on August 1, 2018 to “maximize stocks and ensure optimal growth of grass in fall season” (Irish Farmers Journal).

Among the flagship measures introduced, Kerry Agribusiness announced for the month of August a discount of €15/tonne on fertilizers N/P/K 18/6/12 and 27/2.5/5, as well as on ammonium nitrate.

Finally, producers benefitted from technical support, particularly concerning the set up of a budget, which was allocated specifically to fodder.

Nordic & Baltic countries

Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Poland, Lithuania and Sweden were also heavily impacted by this summer’s heat wave. In addition to the request for derogations from specific greening requirements that they made to the EU Commission on July 12, these countries adopted specific measures.

In Denmark, after having recognised that ensuring adequate levels of animal feed was the biggest challenge to be overcome, the government supported legislation to ease standards for organic farmers. Specifically here below the national measures adopted:

- Organic farming could for a period of time lower the amount of roughage in feed for cattle from 60 to 50% without losing status as organic;

- Organic farming could be granted a dispensation to use fodder harvested on fields undergoing conversion to organic, and therefore being grown according to organic principles;

- It was allowed to harvest grass on grazing areas and use it for feed.

In Sweden, around €116 million were earmarked by the government to benefit the most impacted farmers, in particular the livestock producers, who had to cope with the shortage of fodder. A ”national crisis package” was presented.

In Poland farmers asked the European Union for help in July.

The Polish government announced a compensation program of PLN 500 million (€ 116 million) for thousands of producers affected by the drought. The plan included preferential loans and tax cuts. Almost 187 million euros were spent to help farmers hit by drought, but also floods in the southern part of the country.

Lithuania and Latvia declared the state of emergency. The government made this decision on the basis of the dramatic effects that heat and drought caused to Lithuanian farmers. Specifically, it has been estimated that Lithuanian farmers lost between 15 and 50% of their crops production. This measure allowed farmers who have received EU support previously to avoid sanctions for unfulfilled commitments and facilitate negotiations with purchasers of products. It has been estimated that the country’s farmers lost one third of the harvest due to drought, and the most affected were the ones located in the south of Lithuania.

While in Latvia, one measure that was immediately adopted was the ban on banks to foreclose drought-hit farmers.

Estonia did not declare the state of emergency. However, the Ministry of Rural Affairs in the second half of July 2018, planned various aid measures for farmers struggling against the dry weather conditions. The Ministry called on banks to take into account the situation and ease conditions for farmers who were not able to fulfill all the obligations linked to the drought.

In addition to this, the Estonian Rural Affairs Minister also informed the sector that “when the requirements of a support measure are not met due to the drought, the Estonian Agricultural Registers and Information Board (PRIA) should be notified and it can handle this as an emergency whose related support will not be reclaimed under such circumstances”.

At the end of August, the Estonian Agricultural Registers and Information Board (PRIA) confirmed that this year Estonian farmers were being paid area and animal aids earlier.

Sources

European Commission – Press releases & News

2 August 2018

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-4801_en.htm

30 August 2018

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-5301_en.htm

19 September 2018

https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/adoption-greening-derogations-farmers-impacted-drought-2018-sep-19_en

Joint Research Centre (JRC) MARS Bulletin

17 September

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/jrcsh/files/jrc-mars-bulletin-vol26-no09.pdf

EU media coverage on MS approach

6 April 2018

4 July 2018

http://zum.lrv.lt/lt/naujienos/vyriausybe-del-sausros-skelbia-ekstremalia-situacija-visoje-salyje

17 July 2018

20 July 2018

https://news.err.ee/847982/minister-estonia-not-planning-on-declaring-drought-emergency

31 July 2018

1 August 2018

2 August 2018

https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/duerre-eu-subventionen-1.4079369

10 August

13 August

https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-farmers-still-waiting-for-drought-aid-decision/a-45069512

20 August 2018

22 August 2018

https://www.dw.com/en/german-farmers-to-receive-millions-in-federal-aid/a-45179943

https://www.dw.com/de/dürre-millionenhilfe-für-deutsche-bauern/a-45175387

https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/eil-bauern-bekommen-duerre-hilfen-vom-staat-1.4100251

24 August

11 September 2018

https://www.dw.com/de/dürre-hitze-schlechte-ernte-bauern-spüren-den-klimawandel/a-45380513

18 September 2018