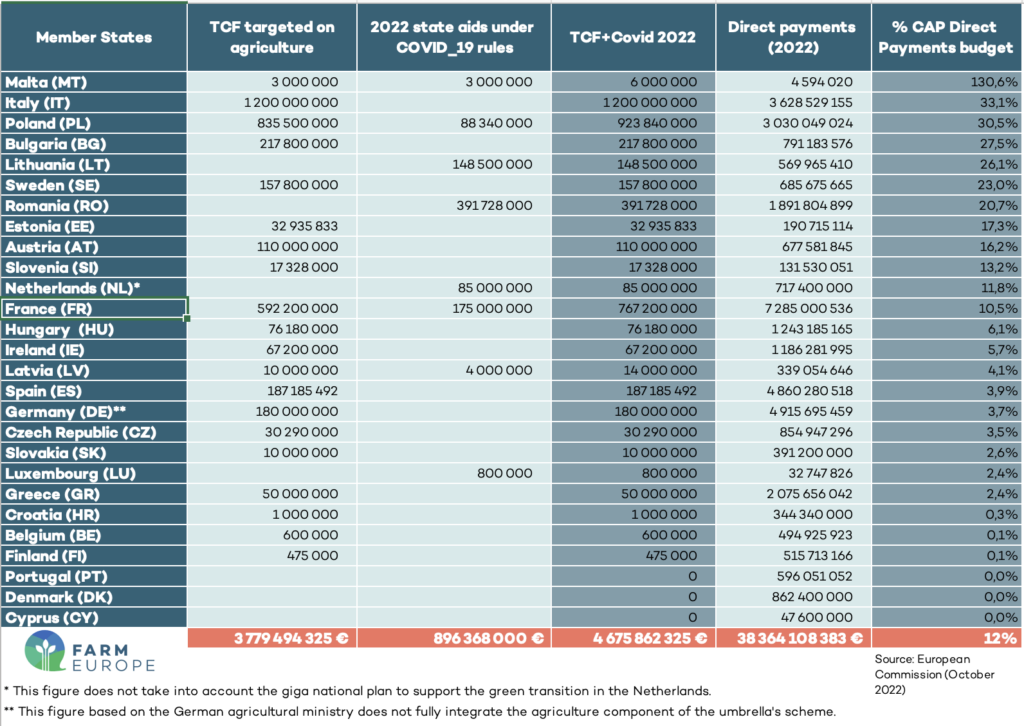

More than €4.6 billion of national crisis measures in 2022

A fragmented internal market

The outbreak of the Russian war in Ukraine not only has sent shockwaves through the energy sector, but also through the agricultural sector in particular via an explosion in energy costs, as well as an increase in input costs, primarily in nitrogen fertilizers.

To address this situation, the European Commission announced in March the activation of the crisis reserve, provided in the Common Agricultural Policy, of around 500 million euros — a historic first as this tool, created in 2013, had never been used until now.

At the same time, the European Commission has announced the possibility for Member States to largely top up this support for the agricultural sector through national aid:

- by authorizing the Member States to finance the aid from the crisis reserve on a 2:1 basis from national funds, i.e. 1 billion euros;

- by validating national aid programs under the temporary crisis framework on state aid in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with a ceiling that should now be raised to 250.000 euros per farm.

At the same time, the ceiling for de minimis aid, national aid that can be implemented without prior authorization from the Commission, has been raised to EUR 25,000 over 3 years.

Member States have made an extensive use of these flexibilities.

The European Commission has been notified of nearly 20 programs dedicated to agriculture for 2022, for a total amount of nearly EUR 4 billion. This represents a 10% of direct aid amounts. Part of this aid — about a third – has been mobilized to deal with the surge in fertilizer prices, through a very uneven geographical and sectoral distribution.

From Italy to Sweden, Poland, Austria and Bulgaria, considerable financial volumes have been released, going far beyond the inflation recorded within these countries, and thus providing more than a simple compensation for the economic loss linked to inflation and the related loss of value of direct payments for their farmers. This clear support to agriculture is not found in other Member States, thus creating severe distortions.

A second group of countries including the Netherlands, France, Germany, Spain, Estonia, Slovenia and Hungary have compensated partially the chock, without making agriculture one of the key sectors assisted as a priority in the face of the crisis linked to the war in Ukraine.

Finally, a third group of Member States, which sometimes have also been hit hard by the crisis, have not been able to provide significant support to their agricultural sector for political or budgetary reasons. This is notably the case of the Czech Republic, Greece, Belgium and Denmark.

These figures — although already considerable — only give a very partial view of the real aid granted by the various Member States, which goes well beyond the strictly agricultural programs notified within the framework of the TCF.

On the one hand, it should be noted that more than €450 billion of state aid have been granted through framework programs intended for the economy as a whole to deal with the war in Ukraine and which also concern the agricultural sector. This does not include the €200 billion program already announced by Germany.

In total, in one year, this is almost the total amount of the European emergency aid to deal with COVID, which has already been released by EU countries in a scattered manner, instead of a well coordinated programme European level.

In addition to the almost €4 billion of aid targeted at the agricultural sector in the context of the war in Ukraine, there is also state aid that paid to agriculture under the residual programs related to the Covid-19 pandemic. €850 million was released in the year 2022, an intensity of state aid of 12% the amount of the first pillar. For a fair analysis, the 25 billion euros released by the Netherlands as part of its national agricultural transition plan, i.e. 2 billion euros per year, should also be mentioned.

In order to avoid severe economic distorsions — in parallel to the much need and legitimate support to the agricultural sector confronted with a serious crisis — there is an urgent need to reflect on the multiplication of aid at national level, rather than at Community level, for a sector covered by a strong common policy. The crisis reserve has shown both its usefulness and its inadequate budgetary allocation on the scale of the European Union in case of a shock affecting all agricultural sectors.

The lack of budgetary margin within the CAP requires an in-depth reflection on the modalities of action to face crises, even more at a time where the new CAP provides further flexibilities. As shown by the scale of financial volumes currently released at national level, a very clear upward revaluation of the crisis reserve is necessary so that it can be the main lever of solidarity for the European agricultural sector, combining reactivity and equity, both between Member States and between agricultural sectors.