September 2018

Executive Summary

In the European Union around 3.6 million farms belong to the EU cattle sector, which represents the 17% of all EU farms. In merely economic terms, these holdings contribute one third to the total EU agricultural gross production value, utilize one third of EU agricultural land and employ one quarter of EU agricultural labour force[1].

The main EU cattle producers are Germany, France, the UK and Italy, which account for half of the gross production value.

Focusing specifically on the suckler cows segment, the sector is characterised by the presence of a vast array of economic interplays: breeders versus fatteners, very well segmented markets’ strategies versus production methods with low differentiation strategies, small farms (50 heads and less) versus larger ones (more than 300 heads), which usually focus their activity either on dairying, rearing and fattening combined or specialising only in fattening, as an example.

Whereas, considering the dairy sector, the picture is slightly different, with less heterogeneous realities. Three main broad groups can be identified at farm level: we have large but also medium size very competitive and dynamic specialized dairy farms, medium but mostly small size farms, often located in remote or distant regions (as mountainous areas), where added value products (i.g. DOP PGI or IGP) represent the main assets and on which well structured commercial strategies can be built. In addition there are medium size farms located in intermediate or less favoured regions, whose profitability relies mainly on products traded as commodities (no differentiation).

If we look only at figures related to income, the EU cattle sector incomes’ level ranges between 2,300 and 65,000 € per year and worker unit. Furthermore, it has been calculated[2] that in 2016 income support via the CAP provides on average 57% of the total annual farm net income, which amounts to 49% in the dairy sector and 100% on average in the bovine meat sector, respectively.

Against this backdrop, the aim of this note is to analyse the main characteristics of the EU beef and dairy sectors, to underline their interlinkages and their potential consequences, highlighting the challenges they are facing and delineating options for sectorial agri-food strategies, which include a balanced policy mix between EU, national and regional levers to achieve growth and ensure an ambitious level of economic, environmental and social sustainability.

Context

The European Commission has presented the proposals for reform[3] of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) alongside with the budget proposals[4] for the period 2021-2027 for the European Union and its policies. Specifically, European farmers’ incomes would be highly impacted[5] by the proposed 12% drop in the CAP budget value (constant prices), which would have a particularly severe effect for the following sectors: field crops, milk and bovine meat. This as a consequence of the intrinsic dependence of cattle, sheep & goat and cereal producers on direct payment for their profitability.

Specifically, the viability for cattle producers would be severely impacted, given the structural characteristic of being a sector for which direct payments represents a large share of income.

Overall, the CAP budget for 2021-27 would see the share drop from around 38% to almost 28% of the total EU budget, which is partly due to the UK’s departure, and for nearly 60% to the will of the European Commission to use former CAP budget for other EU new spending priorities such as security and migration.

The negative economic consequences stemming from the Commission’s proposal would add up to the existing challenges that these key economic sectors have to face, at a time of massive pressure for European agriculture towards more sustainable models in both economic, environmental and societal terms. The role of the new CAP should be therefore to accompany and encourage this development.

The importance of the EU cattle sector, which consists of EU dairy sector and EU bovine meat sector, for the European Union at large, should not be underestimated. Its economic importance in terms of employment at each step of the value chain, rural vitality especially when considering most vulnerable regions, provision of environmental goods and high quality products, is undeniable.

Another relevant aspect that should be underlined is the ever-changing economic dimension of livestock production, considering: (i) level of income support, (ii) price stability, sensitive equilibria in the food chain (i.e. retail buying power in a fragmented supply chain) and the trade dimension.

Both livestock and milk sectors went through difficult times in recent years. Starting from the abolition of the milk quota system (April 2015), high prices volatility at EU and especially global level, lack of competitiveness in comparison with other main producers – profitability being a function of margin/costs (i.e. the U.S., Australia, Argentina and Brazil), increased competition led by new international trade agreements (progressive trade liberalization and therefore more exposure to international markets which entails higher risks of price oscillation and cheaper imports), the impact of climate change (and related demanding mitigation efforts needed – binding targets) recent changes in global supply and demand (increase in protein demand due to population growth), and last but not least, increased societal attention towards quality, safety, animal health and nutritional aspects.

According to the last OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2018-2027[6] global agricultural prices are expected to remain constrained given the forecasted supply growth (especially in the crop and livestock sectors), abundant stocks and global food demand growth. Focusing on specific agricultural commodities, the growth in demand is expected to slow down for cereals, meat, sugar and vegetable oils, however dairy seems to be the exception. Demand growth for dairy products is said to generate therefore higher dairy prices and consequently better margins for producers.

In a situation where it is assumed that the Russian import ban on certain EU agri-food products remains valid at least until the end of the year, latest figures from the short-term outlook for EU agricultural markets[7] in 2018 and in 2019 anticipate a slight increase in EU milk production impacted by unfavourable weather conditions in some Member States, and higher meat availability in the EU (as a result of modest increases in production and higher meat imports).

EU dairy sector in a nutshell[8]

The EU dairy sector is of a great economic value for the EU.

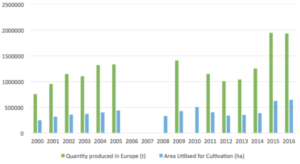

Milk production takes place in all EU Member States and represents a significant proportion of the value of EU agricultural output.

DG AGRI data show that total EU28 milk production is estimated around 160 million tons per year (2016/2017 DG agri data)[9].

The EU’s main producers are Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Poland, the Netherlands and Italy which together account for almost 70% of the EU production. Specifically, the EU15 accounts for a share of 83% in total EU milk production.

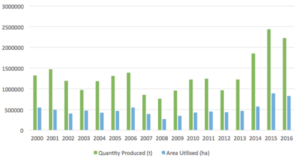

In Europe, according to Eurostat, a number of 1.7 million farms keep 23.5 million dairy cows with an average milk yield per dairy cow of 6,900 kg per year. When considering the last decades, after milk quotas removal in 2015, in line with the market orientation approach given to the common agricultural policy despite the reduction of dairy cow’s number, the yearly milk production per cow has steadily increased. An explanation to this is given by the structural dynamics changes in dairy herds with the growth of the most productive ones.

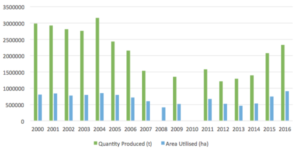

A major factor is the presence of price volatility in the milk markets (usually measured by the coefficient of variation over 3-year periods), especially since 2006 (see figure below), with crises in 2009, 2012 (before removal of quotas, and a major crisis in 2015 after removal of quotas, which has inevitably led to a more market sensitiveness – and in parallel with the slow down of world markets) – between 2008 and 2017, agricultural prices fell by 10%[10].

Not negligible impacts on production levels, difficulties to adjust and usefulness of public signals and incentives were key variables for the sector (i.e. the 2016 incentive scheme was introduced with the aim to reduce voluntarily milk production levels). As also specified in the last EU Agricultural Outlook 2017-2030[11], world market price variability is expected to continue and market unbalances will occur.

At the end of 2017 and beginning of 2018 figures show that milk production in the EU has increased following markets’ signals of increasing milk prices (an average EU milk price of 34 c/kg in March 2018)[12]. Milk prices in the EU have indeed recovered from the low levels in 2015-2016.

To be precise, the majority of farms in the cattle sector in the EU15 are either specialized in dairy or in meat production, while cattle production in MS of the EU13 is located mainly on farms of mixed production focus and small economic size. It has however to be noted that most of the farms belonging to the EU dairy sector are defined as « highly specialized ». Different type of farming (intensive vs extensive), housing systems (indoor and grazing) along with climatic, topographic as well as factors such as farm economics and consumers’ sensitivity, have an influence in the structuring and competitiveness of the business models[13].

Economically speaking, the EU milk sector provides a substantial contribution especially for the most fragile areas, which are naturally disadvantaged such as mountains or other regions of low productivity potential. The same applies to the meat livestock sector. This is mainly due to geographical, climatic and soil conditions. Given the lack of alternative farm specializations in these regions, the agricultural sector capacity to maintain vibrant rural community should be therefore valorized.

This is the dual aspect of the milk sector: economic & territorial dimension, whose sustainable balance needs to be ensured.

The European Union has become throughout the years one of the world’s leading dairy producers. However, unlike its main global competitors (the USA and New Zealand), Europe has not a single industry model.

Roughly and to sum up, four main dairy models exist in Europe:

- In disadvantaged areas (i.e. mountain regions, but as well intermediate regions), where the milk production faces first the challenge renewal of generations as these regions face problems of attractiveness to young people, and secondly very different trends of milk production are present (i) between regions producing high added value specialities and (ii) regions producing milk as a “commodity”;

- In most productive regions, there are two main industry models: (iii) a capital-intensive one that mainly relies on buying in animal feed, and (iiii) a mixed model that relies mainly on food produced on the farm.

Policy instruments & Context

After the removal of the milk quotas in 2015, which represented a challenging moment for the dairy sector, and which followed a phase of policy efforts to increase the power of milk producers and rebalance the milk supply chain preparing the end of quota scheme.

The EU milk sector was not ready when the crises occurred in 2015. Imbalances in overall production, decreasing global markets demands, without the presence of a well functioning EU framework, combined with wrong individual reactions, translated into production increases in face of lower margins per liter and consequently this caused even an higher impact on market prospects. It took almost a year to EU public authorities to act in order to solve markets dysfunctions and stabilise dairy markets so basically adopting their primary role and having in mind that it is less costly and far more efficiently to reduce production than to manage heavy stocks due to the level of overproduction.

This was and should remain a lesson for the future.

Indeed, while the current outlook for world dairy markets is positive, there are some concerns on the capacity of the EU regulatory framework to deal with episodes of extreme market volatility or with a crisis situation after the quota regime, especially in the perspective of ensuring a balanced development of milk production across Europe.

In a nutshell, in addition to direct payments and rural development programmes, the EU dairy sector, which is currently integrated into the CMO Regulation (EU) No. 1308/2013, also benefits from the following measures/market tools[14],:

- Public intervention is available (between 1 March to 30 September each year) for butter and SMP (skimmed milk powder). Before January 2018 it opened automatically, while, after a recent Council decision[15], a quantitative limitation for buying-in skimmed milk powder at a fixed price at zero tonnes for 2018 has been set.

Butter is bought into intervention at 2 217.5 €/t (90% of the reference threshold) and SMP at 1 698 €/t (reference threshold) until a limit of 50 000 tonnes for butter and 109 000 tonnes for SMP. Above these limits, buying-in may continue only by tender (it has to be noted that prices cannot be higher than the reference threshold for SMP and not higher than 90% of the reference threshold for butter);

- If the market situation so requires, other instruments may be activated: a private storage aid for butter, SMP and PDO/PGI cheeses can be fixed (optional measure);

- The reformed CMO allows the Commission to implement any exceptional measure deemed necessary in times of crises (i.g. severe market imbalances), including the possibility to allow POs (Partner organisation), APOs (Association of producer organisation) and IBOs (Interbranch organisation) to take market regulating measures, such as withdrawal of surplus products from the market, private storage, etc.;

- Border protection is high for milk products, virtually limiting imports from third countries to quantities negotiated under bilateral agreements or resulting from the WTO agreement. Specifically, an import regime is applied for dairy products entering the EU. Preferential imports are subject to the issuing of an import licenceand, in general, payment of an import duty (tariff). While concerning exports, since 2009, they have all been carried out without export refunds;

- A “Milk Package” has been in force since 2012, increasing the bargaining power of milk farmers, giving the possibility for MS to declare written contracts compulsory between farmers and milk buyers and processors, fostering the structuration of milk farmers into POs, APOs and IBOs, giving the possibility to farmers to negotiate contract terms collectively via POs, allowing for supply management for PDO/PGI cheeses and enhancing transparency.

It has to be underlined that almost all Member States have adopted national criteria for the recognition of Producer Organisations (POs), though some only recently. The creation of POs requires time and a strong dynamic from farmers themselves. Potential incentives to encourage farmers to enter into joint production agreements have been provided in the reformed Rural Development Policy (support for setting up POs, new measures on cooperation and eligibility of groups of farmers for a series of rural development measures).

- The School Milk Scheme grants an aid for the supply of milk to pupils in educational establishments, contributing to building healthy consumption patterns among children. Under the CAP 2020 reform, MS must have a strategy for the distribution of school milk prior to benefit from the support. A new initiative followed by a political agreement in 2015 led to the single EU School Scheme for Milk, Fruit & Vegetables;

- Marketing standards apply to milk products, drinking milk and spreadable fats, with a view to give the necessary information for consumers to make well informed choices;

- With its promotion policy, strategic priorities for promoting EU farm products and funding criteria in a yearly work programme are defined by the EC. Operators are free to come with concrete proposals that are eventually screened and incorporated into the programmes. A total of EUR 179 million is available for promotion programmes selected for EU co-financing in 2018.

- A Milk Market Observatory has been launched on 16 April 2014 to increase market transparency and help both the actors of the milk supply chain and the public authorities make well-informed decisions. A web interface has been set up through which any interested person can access the latest milk market news, data and short-term analysis on the dairy market.

Two years ago, a milk production reduction scheme officially known as the “Voluntary Supply Management Scheme fo the Dairy Sector” was introduced as a “one-time” exceptional measure. In order to decrease milk production, the scheme offered farmers, who agreed to reduce their milk production, 14 euro cents for every kilogramme of milk reduction over a three-month period (compared to the same period in the previous year). Member States had also the possibility to top up that amount with EU funds distributed as national envelopes for additional support. Dairy farmers were therefore paid according to the actual reduction in production.

In few words, in July 2016 the European Commission implemented this voluntary measure, after an initial reluctance, aiming to support farmers coping with the severe crisis that hit the sector and helping rebalancing the dairy sector. This decision followed the previous measures (late 2015), through which EU funds have been distributed to MS (financial envelopes per MS). The impact of these initial measures was basically a failure in mere economic terms. Conversely, the EU milk voluntary production reduction scheme, financed with €150 million, turned out to be a success: national figures show that almost 48,000 dairy farmers took part in the scheme, leading to a total milk production reduction of 834,000 tonnes. In other words, it has been reported that, «out of the original allocated budget of €150 million, close to €112 million was used to compensate farmers for their efforts». Furthermore, this exceptional measure had quite a substancial impact also on EU milk market prices, whose average in mid-2017 recorded an increase compared to the previous months.

Challenges, dynamics & structural changes

The European dairy sector is facing several simultaneous challenges:

- Increased and recurring price volatility ;

- Strong market crises ;

- Lack or stagnant competitiveness in some regions ;

- Profitability, in terms of capacity to keep milk producers and milk production all across the EU because of diverging production costs in relation to natural conditions ;

- Age of dairy farming population: demographic factor in the restructuring of the dairy industry;

- Industry organisation, together with the relationships in the milk supply chain between farmers, processors and retailers;

- Research & Innovation: the appeal of the industry and its profitability will only be enhanced by upgrading dairy production technologies and skills, which require targeted investments and policies;

- New markets opportunities: the European market is a mature market and the future growth of the dairy industry is and will be exports-driven. This is also a key factor, which is able to ensure the viability of the European dairy industry. Latest projections by the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook estimates for the European Union an increase of its export share to around 28% in 2026, compared to the other four major exporters of dairy products (i.g. New Zealand, United States and Australia).

Since 2007, the global economic environment has been changing quite rapidly. Market volatility has increased, both in frequency and amplitude and this is particularly true for the dairy sector, given its inner dependence on exports and the particular sensitivity of dairy production in Europe to sudden price variations in international markets such as milk powders and butter.

The European Union must therefore enable the dairy sector to:

- Maintain its presence across the whole of the European Union;

- Invest significantly to strengthen its competitiveness in global markets;

- Be sufficiently resilient to market fluctuations;

It is therefore necessary to deploy and structure sectorial strategies for the milk sector and analyze the right and balanced mix between European actions and tools and regional/national level, by first, finding more efficient ways to ensure enhanced competitiveness and sustainability of milk supply across the EU.

As abovementioned, in Europe there are both competitive milk regions and less-competitive ones, with no alternative than milk production, and where milk production is associated with extra costs due to the conditions inherent in their nature.

The profitability of farms, described as “the ability to generate profits”, is determined by a number of financial, property and macroeconomic factors, as well as by structural sectoral determinants and their individual technological and economic characteristics[16]. By focusing on the single aspect of economic margin of farms, the study developed in 2017 by the University of Life Sciences in Poznan (see Ref.12) shows that it is key in determining the development of more targeted agricultural policy tools, and for ensuring the viability of pursued agricultural activity. The author also stresses “the margin level is a synthetic indicator of the financial situation, which fundamentally affects the assessment of the farms’ competitive capacity and thus – their capacity to continue their operations”.

Interesting results are presented by the study:

- “income from milk production in the EU-28 exceeding EUR 51 billion accounts for around 32% of the total livestock production income and around 14% of total agricultural production income;

- specialised milk production is conducted in the EU by more than 572 thousand farms, i.e. 5.3% of all farms (data taken from “Farm structure survey, 2013”);

- specialised dairy farms pursue their activity on the area of approx. 20 million ha, i.e. around 11% of agricultural land used in the EU;

By utilizing specific regression model parameters, author demonstrates that the variability of milk production margin depends mostly on the following farms’ characteristics[17]: forage area, cow herd size, cows’ milk yield, milk prices, energy costs and remuneration costs.

While looking at the dynamic within the sector, the following points are raised and discussed later on:

– the EU dairy farm sector experienced a marked increase in both the size of herd cows, forage area and milk production;

– the production capacity of dairy farms has been seen quite strongly associated with an increase in milk yield, forage area productivity and labour productivity. A strong variability of these dynamics among EU countries’ dairy farms has been recorded along with different technological and economic parameters.

An example is provided by comparing data from 2013, which show that the highest net milk margin was recorded on farms in Romania and Italy, which differ in terms of various parameters. Dairy farms in Romania have low operating costs, fixed costs and costs of external factors, which, as discussed by the study, despite relatively low milk prices, determine the high production margin. While in Italy for instance, the rearing of dairy cattle is conducted on a larger scale, which translates therefore into a high labour productivity and milk yield similar to the EU average.

The study also provides additional comparisons by tackling the low profitability of milk production in some EU countries such as Slovakia or Czech Republic. What has been found as “common factors” are:

- the large scale of production, which is measured by the number of cows and milk production volume;

- the lower labour productivity compared with the EU average;

- low prices obtained and high costs per production unit;

- high cost intensity of milk production

Milk Markets overview – Comparison with World main producers

When looking at the world markets, different factors have to be taken into account:

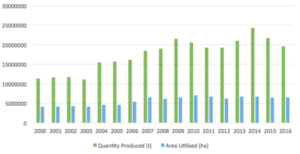

- Global milk production has recovered in recent years and future prospects are optimistic, especially for developing countries (Pakistan and India in particular). World milk production in 2030, according to DG Agri latest estimates which match OECD-FAO ones, is expected to record an annual increase of 16 million t, comparable to the average yearly growth of the last decade, and for a total of around €178 Mt in 2026 (taken 2014-16 as base period)[18];

- New Zealand (world major exporter of dairy product with a share of 32%, primary source for butter and WMP): higher cow numbers and yield progress led to an increase in milk production in recent years. Productivity is expected to grow at a lower pace;

- Australia’s milk supply is slowly recovering;

- The U.S. rose in milk production (+1,76% in May), driven by: +0,8% increase in cow numbers, +1% increase in yield, favourable weather. A slight increase in per capita consumption is also expected;

- Expectations in Europe on SMP stocks release (these are not in view);

- Global demand & exports: SMP exports have been performing well but the market weakened in 2017 (due to slower demand). Increasing demand for cheese, while butter trade was affected by high prices and lack of availability;

- EU trade policy development (Canada, Japan, Australia): example – increased export to Canada via the CETA agreement;

- China’s role: major importer of dairy products – key uncertainty at the moment – strong impact on world markets;

- Brexit: the impact of a hard Brexit would be very heavy for EU beef and dairy sectors. On one side, it will add to the impact of all the EU negotiated FTAs, magnifying the negative consequences. Additional cheaper quantities of beef would reach the internal market, destabilizing in this way the sensitivity of the sector. Concerning milk and milk products, the picture does not differ: Brexit will bring significant pressure caused by added competition in the UK market for EU exporters.

Internal overview -The Example of The Netherlands as a “dairy country”

Analysis and discussion of the study: “Grondgebondenheid als basis voor een toekomstbestendige melkveehouderij” 12 April 2018

The Netherlands is considered as a dairy country thanks to the combination of sufficient rainfall, suitable soil and mild winters, which are all beneficial for the maintenance of grass in good condition and consequently a favourable condition for dairy cows. Dairy farming is the largest land user in the country.

Dairy farming in the Netherlands changed radically in the 50ies, thanks mainly to technical progress. Milk production per cow and per hectare has increased significantly. Better animal care and housing, modern breeding, sophisticated animal feed, artificial fertilizer and improved grass quality were all enabling factors.

Dutch dairy farming was a land-based sector. Therefore, the farmer had sufficient land available to produce grass and maize for the cows and to make optimum use of the manure of those cows for the growth of the grass and the maize.

During the last years, Dutch dairy farmers started a process of restructuration by investing and expanding themselves.

Dairy farming became year after year more intensive, the farmer had to transport more manure to other agricultural companies and more feed from third parties. As a consequence, this has led to negative consequences for nature, the environment and the landscape.

Focus on the Economic challenge

Instead of producing more and more milk at lower cost price, the challenge for Dutch dairy farming is to make the switch to milk with more added value. However, the restructuration process increasingly towards large-scale dairy farming with associated financing costs and a higher production per cow, tends to have reached its limits within the Dutch context.

Furthermore, a particular attention has to be given to “exploring niche markets”, given that the domestic demand in the EU (quite stagnant) combined with the global demand of milk and dairy products suggest such a move.

For instance, by allowing and easing (at the national level) supermarket chains’ collaboration with the dairy industry, could set up chains for milk with a higher social added value. Indeed, this is only one of the possible business strategies that could be structured, since only a segment of consumers is nowadays willing to pay an extra price for this.

It is relevant to note that maybe the biggest challenge that both milk and beef sectors have to cope with is to find a way to improve the efficiency and productivity of production methods in an environmentally sustainable way, while increasing their market return thanks to a good communication to consumers. This because issues as environmental and socio-ethical/nutritional aspects, such as animal welfare, climate impact of livestock production, healthy diets are shaping the policy agenda, and consequently the need for rational use in livestock and dairy production will be the baseline.

Sector’s self-sufficiency in raw material

Substantial steps towards a high level of self-sufficiency will be needed in the coming years.

This key figure is the extent to which the farmer is able to grow protein for his own animals’ feed from his own country or nearby. In addition, the cultivation of own protein makes the farmer less dependent on global sources of protein whose price development is becoming increasingly volatile and which is expected to rise in price in the coming period.

In addition, by ensuring a higher degree of self-sufficiency in protein, the import of protein-rich raw materials from outside Europe can be significantly reduced.

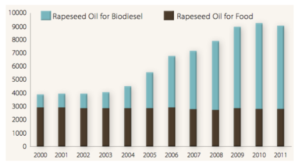

Along this path, in order to achieve a higher production of forage directly on farm and limiting therefore imports, major actions should be targeted at increasing grass productivity and protein content of EU cereals, and as well securing the sustainable production of EU rapeseed meal.

Questions/Issues to be tackled to adopt the right policy approach

What could be a strategy for producers to continue to exist, to be competitive on both the internal & the global markets?

- Tackle volatility and market crises via new tools and more solidarity across the EU food chain ;

- Stimulate targeted investments to increase both competitiveness and sustainability;

- To promote EU quality (safety, quality of products and quality of ways of production) on EU markets and worldwide ;

- Give value to by-products (energy)

- Regional approach to better structure processing, in particular in areas facing competitive challenges ;

- Support farmers with knowledge, training and advisory services on how to effectively operate producer organizations ;

- Adopt effective and affordable tools to improve the less sustainable practices (e.g. manure/nitrogen management); to reach common EU standards to secure the perception on world market of EU high quality products ;

- Sectorial economic integrated strategies of development with targeted tools and financial means, mobilized in a flexible way other the period, to accompany the implementation of these strategies (CAP role)

Actions: EU, National & Regional/Local

On the basis of the elements listed in the paragraph above, effective actions at different levels (EU, national and local ones) could be structured.

In particular, when considering the local/regional level, the focus should be on deciding the type of structuration process – by both better structuring the upstream agricultural sector, and strengthening the weight of the upstream, or even allowing for reconversions.

Sectorial integrated strategies need flexibility in the possibility to mobilize tools making up a sector’s economic strategy (i.e. via specific investments, training, exit plan) on the basis of a kit of EU measures that can be flexibly mobilized in a financial envelope defined in relation to the CAP strategic plan.

In practical terms:

- How to tackle markets and prices volatility effectively – more effective risk management tools to be deployed via the new CAP and following what has been proposed with the Omnibus regulation

- Crisis situations: A European Crisis Management Fund in agriculture, financed by an adequately equipped multi-year crisis reserve, must be carried out and take over the IST tools when risks become deep crises (see related Farm Europe note)

- Innovative strategies to ensure and enhance the competitiveness of the sector, to keep the recent dynamic. Role of Innovation, Research and Technology: in terms of infrastructure improvements, genetic (fewer inputs and better resistance); – One possibility to be further investigated: recent advancements in beef and especially dairy cattle breeding thanks to technological/genetic improvements, which could play a decisive role and a driving force behind increased economic efficiency and consequently profitability of dairy farms.

- Improve sector’s capacity to get organized (i.e. via contractual/commercial relations, participation of dairy producers to recognized POs);

- Strengthen the capacity to negotiate prices and volumes ;

- Effective and shared export action;

- Ensure a better positioning according to the product value and respective target market;

- On consumption (internal market): tackle the nutrition/health related issues concerning dairy products – dietary habits changes – meet consumers/societal ‘expectations – Nutritional quality of milk products (source of calcium and protein) – Link with production methods – Diversity of products;

- For less competitive regions:

- role of PDO/PGI quality logos;

- tailored regional sectorial strategies for less competitive regions without specific PDO/PGI assets based on structuration, innovative investments and developments of co-productions.(incl. energy).

- Environmental sustainability commitments/actions: enhance the capacity of the sector to respond to consumers expectations and concerns when it comes to residues, treatments and climate change mitigation ;

- Commitment of the sector to the climate aspect: build on the achievements over the period 1990-2010 and make new steps forward;

- Develop the Circular economy concept.

Overall, when dealing with the whole “environmental sustainability dimension”, which represent one of the pressing challenge that the EU agricultural sector has to face, an ambitious EU program for double performance (economic and environmental) should be deployed.

Specifically, increase the dissemination of high-tech farm production methods/practices within the beef and dairy sectors would provide tangible provide results in the inputs optimisation, thus reducing the environmental impact of the agricultural sectors concerned and increasing their competitiveness vis-à-vis the other major producers.

However, given that the picture now of the uptake rate of these high-tech farming techniques (smart and digital farming) remains low and differs widely among EU Member States, the new CAP should accompany the transition towards a double performant EU agricultural sector by proposing an ambitious and clear program.

EU Beef sector in a nutshell

The European beef sector is at the foundation of the economic fabric of many rural areas across the European Union. It provides a great number of jobs at each step of the value chain, from the farm to the sale point, encompassing a range of intermediaries, supporting industries as well as sales and retailing.

In this context, the suckler herd – an important segment of the EU livestock sector – is a key player, not only because it provides more than one third of the beef consumed in the EU, but also for its strategic role in very specific EU areas, – mainly located in Ireland, France, the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, Portugal and also, more and more, in Poland. Niche market is also present in many other EU Member States, with demand rising in countries like Finland and Sweden. It is also important to highlight that in many areas; this specialized breeding system cannot be replaced by other farming activities. This is due to the agronomic profile of the land.

However, the contribution of this specific sector to the EU economy is too often underestimated.

The European beef sector is undoubtedly one of the most important agri-food sectors in Europe, if not the most important, in terms of local development and of employment, in several regions of the EU.

However, despite the best efforts of public authorities and of numerous private initiatives, this sector has been facing structural and recurrent crises for almost two decades in various parts of the EU.

Ongoing changes in consumption patterns, technological evolutions, and of policy and international commerce ensure a particularly uncertain future for the sector, or at least one, which is difficult to read.

In this context, the sector confronts a major challenge: to grow and develop, despite the uncertainties of the future, to build a collective political and economic strategy, to seize opportunities which present themselves on both the European internal market and on external markets, and to nurture a new link with citizen-consumers.

Policy instruments available

By considering EU policy, as well as the policies of its leading member states in beef production, and in parallel to the policies pursued by the U.S., Brazil, and Argentina, conclusions may be drawn on how best the EU may support and secure its beef sector in the face of new and unexpected challenges.

The Common Market Organisation covers the beef and veal sector, with market instruments initially conceived to stabilise the sector when deemed necessary through:

- Public intervention: may be opened by the Commission if, over a representative period the average market price in a Member State or in a region of a Member State is below 85% of the reference threshold (EUR 2224/tonne). Since the 2013 reform, intervention became dependent on the Commission’s will, rather than being triggered automatically once the threshold price is reached. However, the implementation of this tool is very unlikely, taking into account the level of the threshold. At its low point during the 2001 crisis, for example, the EU beef price reached €2318/t (OECD);

- Private storage aid: the Commission may decide to grant private storage aid by taking into account average market prices and the reference thresholds and production costs for products concerned, as well as the need to respond quickly to an emergency market situation having a significant negative impact on margins in the sector;

- Import tariff quotas: the Common Market Organisation (CMO) empowers the Commission to set the measures to manage import quotas. Most of the tariff rate quotas agreed for the beef sector are managed by DG AGRI;

- Collective negotiation: producer organisations (POs) in the beef and veal sector may negotiate contracts for the supply of live cattle under certain conditions. For each organisation, the quantity of beef and veal covered must not equate to more than 15% of the total national production (this changed with the Omnibus regulation from January 2018);

- Exceptional market support measures: measures which may be decided and implemented by the Commission in cases of animal disease or loss of consumer confidence;

These measures complement the existing direct support schemes of the current CAP, which include compulsory schemes for all MS – basic payment (or Single Area Payment) per hectare and voluntary schemes (optional for MS), Voluntary coupled support (VCS), through which Member States have the option of providing limited amounts of “coupled” payments (between 8% and 13 % of the national envelope) to those sectors or those regions where specific types of farming or specific agricultural sectors undergo certain difficulties and are particularly important for economic and/or social and/or environmental reasons. The Commission has flexibility to approve a higher rate where justified. In addition, there is a possibility of providing an additional 2% “coupled” support for protein crops.

With the new CAP proposals, the European Commission proposes the 13% to become 10% and it added the possibility to set up operational programmes up to 3% of 1st pillar national envelope. Furthermore, the proposed reform proposal plans to merge the current CAP greening and the conditionality in force into a new, expanded conditionality applying to 100% of 1st pillar aid. However, Member States are able to define the scope covered by a number of these new conditionality requirements. Current greening’s exemptions would not be valid anymore.

Furthermore, a new measure is proposed in the first pillar to finance new environmental actions (eco-scheme). This measure is intended to finance the implementation of environmental requirements going beyond the new conditionality.

Throughout the years, the European beef sector, and especially the suckler cows sector, has been unable to recover and to develop a long-term profitability. Therefore, current policies which were weak in supporting the beef sector during these last years and decades should be questioned and analysed with a strategic approach.

Main Objectives to be achieved by a sectorial strategy

To improve:

- Power of producers organisations in the food chain ;

- the structuration of producers into more powerful organisations ;

- Joint action among farmers and across the food supply chain in order to foster efficient use of resources, product development and marketing opportunities

- Productivity and competiveness;

- Segmentation of the beef markets and correlated strategies of marketing mix

- Regional strategies of (re)structuration of the sector and its farming component

- Use of risk management instruments and prevention strategies;

- Invest in the double performance of the sector : linking increase of profitability and environmental and climate change performance

Challenges – Focus on Beef

Political aspects: the safety nets put in place have proven to be ineffective for the sector, and premiums to offset its new market-oriented character have not altered the difficult economic reality for European farmers, whose incomes are modest and dependent on aid – the public financial effort (notably coupled payments) is to a large extent absorbed by other players in the sector – the work at producer level is not rewarded by the market as it should be for an healthy economic sector. Other actors, too, in particular slaughterhouses, often achieve low level of profitability. In short, the sector does not respond well to short-term strategies, and investments take between 15 and 20 years to have a real impact.

Sanitary and nutrition aspects: since the end of the 1990s, the public perception of beef has changed. While previously a central element of a balanced diet in the opinion of nutritionists, multiple health crises and the debate surrounding climate change have transformed the image of meat and its place in nutritional recommendations. The world market is changing, with traditional powers – the developed countries – focusing on value, while dynamic powers – which are more diverse – have very different requirements in terms of quality standards, and are therefore also more difficult to understand. In addition, the livestock industries are also affected by climate change, with rising temperatures being associated with increasingly significant and more diverse epizootic pressures.

Economic aspects: the livestock industries are mostly located in areas adversely affected by economic globalisation and by the opening of borders in the agri-food industry and beyond. Often isolated, they do not immediately benefit from the economic dynamics generated by the opening of new markets and the development of new technologies. They face a multifaceted challenge:

- The paradox of being forced to turn to the world market – where the growth opportunities present themselves – while simultaneously being weakened by that very world market, where the highly integrated operators pose fierce competition, having completely redesigned the fundamentals of the sector. This is especially true of Brazil, which has turned beef meat into a ‘commodity’ – in the last decade, productivity in heads per hectare increased by 25%, and the country produced 9.92 million tonnes of beef and veal, or 16.85% of the global total, in 2014 (USDA)._ Virtually all of the ongoing free trade agreements place the industry in a defensive position (Mercosur, TTIP, and Australia, in particular).

- The difficulty the sector faces in controlling its own destiny, given the competition posed by the dairy herd on the beef market, which provides around 60% of the beef consumed in Europe. This poses a problem, as the dairy herd was previously constrained by the European quotas and in decline due to the increased competitiveness of the dairy cow, while the current expansionist strategy of Europe’s dairy sector shuffles the deck and puts pressure on specialised breeders.

- Slow investments related to cattle farming and low prospects for depreciation are associated with difficult working conditions.

- A scenario of a “three tiers” EU sector with a sector in Eastern Europe focusing on low production costs to take advantage of their competitiveness to enter the market, switching from milk to meat; a sector characterised by larger farms focusing on breeding cattle in association with arable crops and forage for own consumption and producing enough to gain some power of negotiation – at least locally (semi-direct sale, regular contracts); and a sector of smaller-medium size farms with basically no bargaining power.

Reasons for the EU to take action

Confronted by this bleak situation, there are nonetheless very real prospects for the European industry, which can count on its capacity for resilience and the remarkable attachment of the livestock community – mobilised, passionate about their work, and in possession of extensive know-how, renowned across the world – associated with products possessing an extremely strong identity.

Beyond the fundamental human factor, given the strong local roots of direct and indirect activities related to the livestock sector, markets offer room for a renewed and ambitious strategy which takes into account the major challenges facing the EU: sustainability, growth, and employment.

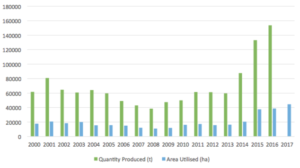

In terms of both growth and jobs, Europe has missed the first global boom of beef meat, overtaken by emerging actors – most notably Brazil (Figure 1). The EU is nonetheless an important challenger – a position which it does not hold for any other important agricultural production.

The sector is the economic heart of many remote areas, and can be, in these regions, a real fulcrum for the revival of employment around products with a strong identity. The potential for growth of developing countries is far from exhausted: beef consumption per capita remains three times lower than in developed countries.

According to the OECD, global demand for animal protein is due to grow by 1.6% per year over the next 10 years, driven by revenue growth and urbanisation. In total, 58 million more tonnes will be consumed in 2023 compared to 2011-13, this increase being concentrated primarily in Asia, South America, and Africa. It should benefit in particular the poultry and sheep meat sectors, but all meat, including beef, is expected to see double-digit increases, with prices also due to rise. EU beef meat consumption began to recover in 2014, by as much as 1.8 kg per capita, at trend which is set to continue (European Commission, 2015)._

Moreover, in the background is the question of the durability and appropriateness of the expectations of Europeans, given the products to which they have access.

To put an end to local production would lead to first, an externalisation or outsourcing of greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the pressure on particularly sensitive zones such as the Amazon, and preventing the EU from meeting the climate objectives for which the EU sees itself as an avant-garde actor; Second, the abandonment of the extremely high standards of production and animal welfare – the EU has not succeeded so far, despite numerous attempts, to integrate this dimension into international agreements; and finally, in the longer-term the EU would be faced with products which are controversial, both ethically and sanitarily, rightly or wrongly – such as the use of cloning, against which European citizens retain a very strong resistance.

On this basis, it is appropriate to question and advance the sector’s strategy, mirroring the political tools in order to contribute to the implementation of a winning strategy for this sector.

Elements to structure an effective strategy

Research and innovation: animal genetics and improved livestock management (buildings, animal feed), gains are made both in better meeting consumers’ expectations in terms of products available and marketed, and in reducing the environmental footprint of the production process – the FAO predicted that Grassland carbon sequestration could significantly offset emissions even without any farming system change, with global estimates of about 0.6 gigatonnes CO2-eq per year (UN FAO, 2013)._ In matters of public health, too, it is likely that scientific solutions will emerge on a large scale to remove elements considered a health risk by the WHO due to the excessive consumption of meat. It should mobilise the available knowledge and accelerate its implementation in the sector itself.

Better market segmentation: Linked to the research effort, it is necessary to clarify what is on offer to consumers. A number of market segments are emerging, both in Europe and internationally. The challenge is for each of these segments to find stability and clarity without relying excessively on others. Four components, corresponding to four different sectors of production, may be identified:

- Meat from the dairy herd: low-end (but a source of instability for other sectors, depending on the variations of the price of milk);

- Calves from the dairy herd whose quality is improving due to technological advances related particularly to sex-sorted semen: entry-level;

- Breeds of beef for the “general public”, with large production volumes, of a high level of security for consumers;

- High-end, with more specific breeds rooted in exceptional terroirs.

These two latter components are at the heart of the strategy for recovering the strength of the livestock sector, in coordination with the two former components. It should ensure that the dairy herd does not hamper the ability of the suckler cow sector to deploy an effective strategy, while maintaining its role as an additional source of income for dairy farmers.

Increased coordination between actors of different sectors and an enhanced level of understanding of consumer expectations at ever link in the chain. This should both allow an increased level of responsiveness and adaptation between markets and production in order to optimise value creation, and accelerate the dissemination of innovation within the sectors. Coordination at each level of the sectors should enable a pool of strategies for different breeds and for marketing prospects.

Optimisation of logistics situations, including in relation to the debates on animal welfare and transport emissions.

Effective communication systems and quality assurance labels to fully highlight the efforts of producers to consumers – and to benefit from appropriate levels of compensation with regard to segmentation and production structures. Moreover, in parallel, a thorough knowledge of both European and international markets is necessary in order to promote, as far as possible, each piece of meat, by finding the market where it is value and fulfils a gap in consumer demands.

When compared to other breeding activities, the EU beef sector production has distinctive traits, which make it particularly exposed to external factors:

- Tight margins, when looking at producer’s prices;

- Generally low level of profitability, when considering the complexity of the production systems overall;

- Low level of elasticity;

- High global competitiveness vs low internal competitiveness (structurally between 70% to 90% of the incomes in the beef sector depend on CAP subsidies);

- Animal welfare concerns supported by activists’ campaigns;

- A mix of positive and negative environmental impacts (biodiversity, carbon sequestration and emissions).

In addition to this, profound changes in consumption, technologies, public policies and international trade are combining together to make the future unpredictable, or at least difficult to foresee, in particular due to:

- the threat of a more intense competition from the bilateral agreements agreed (Canada) or currently being negotiated – namely Mercosur, Australia, New-Zealand, not mentioning the US;

- the lifting of milk quotas, which is disrupting the sector’s equilibria through renewed growth in the dairy herd, which already supplies two thirds of the beef consumed in Europe.

- Suckler beef is as well especially vulnerable, with Brexit and the risk of cheap beef imports under CETA, possibly other trade deals the EU is negotiating currently and trade deals, which the UK may ultimately negotiate with non-EU countries after having left the EU.

Consequently, the sector is facing a double challenge:

- Building a clear and concrete vision for the future and, to do so, devising a strong market-driven business strategy for the sector as a whole. This strategy must enable the industry to seize opportunities both within Europe and beyond, as well as help it to adapt to changes in demand.

- Designing and contributing to build the most suitable policy tools to support and accelerate the implementation of this business strategy, valorizing the wide diversity of culture and economic models in Europe in this specific sector and laying down the foundations for a common European approach, with flexible and relevant tools developed and adapted to this diversity.

Yet, despite the efforts undertaken, especially through the Common Agricultural Policy, the sector has been struggling with recurring structural crises for almost three decades now. The impacts of these crisis have affected different regions in the EU, at different times and in different ways, depending on their production models.

In this context, it is more than urgent, on the EU market, to better valorize products, to build efficient meat supply chain focusing on modernization, structuration as well as viability and to cope with the challenge of market volatility and crises. While, on the Global market, to ensure effective promotion measures and a meaningful trade agenda, always bearing in mind the high sensitivity of the sector. The EU has definitively a key role to play as a supplier of safe and quality meat products. The option that the EU Commission included in the CAP proposals of structuring operational programs that can be opened to other sectors than those that benefited until now (wine, fruit and vegetables), in order to develop sectorial stratgies, will certainly play a role on top of notably current 1st pillar tools (decoupled and coupled payements). .

The EU beef sector clearly has the capacity to seize the growth opportunities stemming from the increase in beef meat global demand forecasts for the upcoming years.

However, the current market situation for bovine meat is quite worrying both in terms of economic and societal aspects.

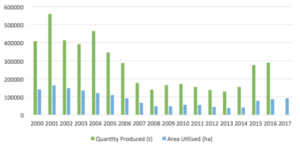

Starting from the last years, a steady increase in slaughtering (linked to the difficulties experienced by the dairy sector), so a production increase, has affected producer’s prices consequently. Latest analysis (EU Agricultural Outlook 2017-2030) confirms that beef production remained stable in 2017, following the increased number of in slaughtering of heifers. However, the overview provided by the study shows that by the end of the outlook period (2030), beef production is expected to fall to 7.5 million t. Main drivers of this decrease are to be found in: lower consumer demand (internal market) and recent developments in the dairy and suckler cow herd, but at a slower rate than in 2005-2013.

The situation in Ireland, the Netherlands and Poland provides an overview of the ongoing economic developments.

In 2017, Ireland experienced 200,000 more cattle for slaughter than in 2015, in addition to a chaotic situation on traditional export markets (Russia, Turkey) and the sharp fall of the pound in the wake of the Brexit referendum in the UK, which is the biggest export market for Irish beef producers.

The same type of impact was faced by the Netherlands. This is due to the deliberate choice of the NL milk producers to increase the dairy herd in 2015 and 2016, ahead of the implementation of the new domestic regulation on Nitrogenous effluent release. As a consequence, at the end of 2016 data showed that there were already 160,000 more NL cattles for slaughter than in 2015.

On top of this, Poland appeared as a newcomer with strong ambitions in the sector. Because of the milk crisis and the strong competition of western milk producers, many polish producers are converting their milk herd into suckler herd. Between 2004 and 2016, the polish beef meat production register a 66% surged, Poland becoming the 7th EU producing country, exporting 90% of its national production. (Poland being traditionally a pig meat market).

Furthermore, another issue of concern is the surge of young calves from the dairy herd, which are not deemed as suitable for viable beef production system. One of the few options is to export them.

Accordingly, the links between dairy and beef sectors should be tackled thoroughly, since outlooks for the first one are positive, especially in terms of profitability.

The forecasted expansion of the dairy herd should not happen at a detriment of the specialized beef herd – According to estimates (DG Agri) almost 2/3 of the EU cow herd comes from dairy one.

At the same time, the beef sector is facing two communication challenges:

- On one hand, some big EU competitors – in particular from South-America – are spreading the idea among EU consumers, via aggressive trade and promotion actions, that quality beef = non-EU meat.

- On the other hand, activists are challenging beef meat consumption as such building their campaigns on misinterpretation of nutrition science and hard hitting animal welfare actions.

The EU should work actively against these two highly dangerous and false misconceptions and messages from both an economic and health point of view.

Old story but simple reality: ruminants like cows can digest plants that are indigestible to humans. They make available high amount of proteins for feeding people.

A certain number of ideas come up regularly in discussions at EU level and they could be definitely considered and evaluated as a possible basis for a successful European business strategy for the EU’s suckler herd. Specifically, on the basis of currently available information, and bearing in mind the challenges we can foresee, Farm Europe believes that the following could be key ingredients in a common European strategy, and that they could offer a starting point for a discussion on such strategy:

Market segmentation (ensuring production is demand-driven). The priority must be for the sector as a whole to reflect on remodeling its product offer, in order to make it clearer and closer to consumer demands. This implies a root and branch review of all the parameters that govern the sector, niche market, and supply chain dynamics – from breeds to industry organization, to the point of sale, including research, innovation, and market prospects for European beef products. On the demand side, suckler beef needs to be differentiated as a premium product as part of a comprehensive plan to segment the market and provide a means of surviving the damage caused by trade deals.

The long-term success of this approach remains on ensuring a more harmonious co-existence between suckling and dairy herds.

Three market segments seem to emerge:

- A. Entry-level: mainly carcasses of culled dairy cows, but also entry-level cuts from suckling livestock of lower quality used for minced beef, processed products, entry-level cuts of beef ;

- B. Mid-range: mainly consisting of suckling livestock, including, but not limited to, large, well-known and developed meat breeds such as Angus or Charolais (cow or YB meat depending on markets);

- C. High end: productions anchored in terroirs, with a very high reputation potential, valued at all stages of the chain of production and marketing as an exceptional product. These represents signs of quality (PGI, labels, etc.).

The challenge is to develop economic coherence for each of these segments, both at the level of livestock systems and at the level of the sector, through research and innovation, but also through the promotion, organization and the transfer of value to producers.

- Research and innovation through improved animal genetics and by enhancing farming practices (in buildings, animal feed etc.), it is possible to make advances that will better satisfy consumer demand in terms of products on the market and societal expectations in terms of health, environment and animal welfare. Effective communication, information and decision should be science-based, with a clear commitment of all stakeholders in that respect (from economic actors to medias, from decisions makers to NGOs), while not discouraging research and innovation in this field.

- Structuring the sector will require two types of action:

a. greater coordination: between producers, processing and distribution.

It has become an absolute necessity to organize the sector, including coordinating at strategic market segment level or, when deemed relevant also at local producing regions’ level. This coordination should result in a fair return for the first stage of the industry’s supply chain – and an improved awareness across the whole chain in relation to consumer demands.

Such coordination must strengthen the industry’s ability to respond quickly and adapt its products to new opportunities, thereby creating value, and it must accelerate the take up of innovations across the whole sector. Coordination of the sector and its different markets and supply chains, should lead to the uptake of market segment strategies covering breeding and commercialization dimensions.

This enhanced cooperation within the supply chain would lead to an array of positive outcomes for all the actors: improve the production planning on the basis of market demand, organize information/awareness programs to the consumer, as well as product promotion activities/marketing, simplify the uptake of research and innovation for the sector and enhance the export capacity in foreign markets.

b. Firm-level re-structuring including farms and industrial firms (slaughterhouses) so that each partner in the chain is able to invest thanks to a fair level of profitability, develop the business sustainably, and be strong enough to play a full part in the devised strategy.

This firm-level and sector-wide re-structuring goal should (1) be managed taking into account the characteristics of each Member State (and also specific cost issues applying to firms) and (2) take into account the particular characteristics of producing regions in terms of their respective models (suckling, breeding, fattening, etc.).

This is a challenge that bovine meat sector has in common with other agricultural sectors in intermediate and less favored areas. Therefore, there is undoubtedly a necessity to tackle this Common challenge.

In parallel, enhanced action should be pursued to encourage investments into bio-energies, which can both strengthen the viability of certain farms and contribute to climate change mitigation, aiming towards the life-cycle perspective, by linking production to existing farm resources.

3. Commercialization. Effective communication systems and quality labels are needed so that consumers are made fully aware of advances in quality, the environment and animal well-being – and so that operators obtain a meaningful return on investment consistent with the market segment and the production infrastructure in place.

An enhanced communication effort should be encouraged in order to highlight the specific features of the EU livestock sector, in particular to differentiate it from feedlots of the American continent.

In Europe, structurally falling consumption makes it necessary to pursue offensive strategies to defend the positions of EU businesses relative to international competition in each of the three market segments, as well as to promote each cut of beef and each partner in the supply chain as effectively as possible by identifying the segment in which it or they would be most successfully marketed.

Marketing and discount sales strategies should moreover be managed so that beef is not a loss leader, and marketing truly focuses on selling surplus stocks; Prices in segment A do not drag prices down across the whole sector.

Internationally, real opportunities exist, especially with respect to live cattle, high-end products (segment C) and co-products.

Effective communication and marketing strategies need to be implemented for both the EU internal market and international markets. An ambitious export strategy should be stepped up, based on efficient tools acting as a lever to develop markets such well-targeted promotion actions.

—–

On top of the usual policy tools included in particular in the CAP, the European Union must mobilize its capacity to strengthen the sector, especially in order to anticipate the impact of trade negotiations that weaken the EU beef meat sector, already confronted with structural and recurring crisis.

Such revitalization plan should not be limited to a policy of budgetary transfers – even though their legitimacy must not be put into question (Coupled Payments, LFA payments). The European Union must go beyond these tools offering levers to structure, modernize and promote the EU suckler herd with the support of well-calibrated financial supports.

The objectives of the toolbox could be summarized as follow:

- Organization, market segmentation and structuration:

- Building a strong market-driven business strategy for the whole sector, based on clearly established market segments;

- At local level: helping producers to invest and make money out of their work (organization, investment, including in bio-energies);

- Building efficient meat supply chain (including via a proper competition policy and the extension of the milk package – see annex) and more innovative and modern slaughterhouses;

- To cope with the challenge of market volatility:

- Building tools, which are able to improve market resilience (ex: mutual funds) to limit the shock in the milk sector, which have in turn collateral effects on the specialized beef sector;

- Coping with sanitary and climate risks, including taking into account grass land model which is an important carbon traps or fattening systems with climate-efficient feeding and effluent management practices;

- Achieving greater coordination in the supply chain (between producers and other partners in the supply chain) with enhanced possibility to discuss and negotiate prices and volumes.

- Setting European multiannual tool to manage extreme crisis; financing without delay exceptional measures to rebalance the market:

- Triggering, when necessary, market management tools as it has been done for the milk sector in 2016. In certain cases, well organized mandatory storage action could be more easily set up targeting the dairy herd and taking into account the lower level of losses in relation with storage process, than products with higher value. For the suckler herd, possible measure of live storage on the farm might be explored, with the aim to rebalance the market temporarily, covering feed costs, etc.

- To promote the EU model, its positives externalities and the effort already done in terms of sustainability and, especially, to highlight the viability and specific features of the European beef sector via adequate marketing tools and well-funded promotion campaigns.

- To enhance private quality scheme and GIs systems: high quality beef could also move in this direction. The idea could be to develop new quality schemes or new criteria (on grass-fed beef for instance or other breeding practices that have a good impact on fat content) linking it with the idea of differentiation (mid-range market). Certain GIs could be developed, especially for the high-end segment. Quality schemes must be able to address consumers’ concerns as well as they could be developed in relation to animal welfare and industrial livestock production methods, while facilitating the marketing of the products.

- To promote further the sustainability of the EU production systems (innovation, smart policy and consumer awareness), with well-designed climate actions.

- To Increase and maintain the livestock sector competitiveness in each area (intensive livestock areas vs less developed areas).

EU standards need to be powerful at global level; However, in Europe we cannot forget entry-level products. The focus should therefore not be only on high-quality cuts. We need to be competitive also on these entry-level products which will have to face competition of non EU products and to segment very carefully the EU meat markets in order to limit the potential competition of non EU products on the other market segments.

Farm Europe strongly believes in the potential of the EU beef sector, both economically and in terms of sustainability, against the current pessimistic visions of the future combining de-growth and abandonment of land currently experienced by producers.

The think tank considers an absolute priority to invest and reflect on the future of this sector confronted with structural economic changes.

Of course, given the complexity of this sector, there is no magic wand. Nevertheless, the objective should be to capitalize on the assets of this strategic sector for many regions in Europe, not adopting a defensive approach. In other words, to focus on a true economic ambition for the future.

Implementation of the strategy should help to secure the internal market and reduce imports. Specifically, it is crucial for the European sector to retain control of the high added value segment, which makes it more necessary to have an ambitious strategy for the specialized sector – and consistency in the commercial strategy of the EU overall.

Measures exist within the current framework of the Common Agricultural Policy, which could be mobilized. Beyond that, a strong revitalization plan must be shaped at EU level.

Additional budgetary resources should be targeted on the key elements of an ambitious policy strategy, complementing existing tools, with the objective of leveraging and accelerating the structuring and modernization of the sector by offering to producers the right tools to build on their future.

References

Research for AGRI Committee – The EU Cattle Sector: Challenges and Opportunities – Milk and Meat – February 2017

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2017)585911

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council – On the impact of animal welfare international activities on the competitiveness of European livestock producers in a globalized world – Brussels, 26.1.2018 COM(2018) 42 final

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/animals/docs/aw_international_publication-report_en.pdf

Vandecandelaere et al. “Strengthening sustainable food systems through geographical indications – An analysis of economic impacts” FAO, Rome 2018

http://www.fao.org/3/I8737EN/i8737en.pdf

EY, Analysis on future developments in the milk sector – Prepared for the European Commission – DG Agriculture and Rural Development, Brussels, 24th September 2013

Press:

https://www.agriland.ie/farming-news/move-over-dairy-oatly-is-in-demand/

https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/final-figures-reflect-success-eu-milk-production-reduction-scheme_en

EU Dairy Farms Report based on 2013 FADN data. (2016). European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, Brussels.

Farm structure survey 2013. Key variables: area, livestock (LSU), labour force and standard output (So) by type of farming (2-digit) and agricultural size of farm (Uaa).

[1]Source: Research for AGRI Committee “The EU cattle sector: challenges and opportunities” – European Parliament – Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, February 2017

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/585911/IPOL_STU(2017)585911_EN.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] Link to CAP reform proposals: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/publications/natural-resources-and-environment_en

[4] EU budget legal texts available here: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/publications/factsheets-long-term-budget-proposals_en

[5] A decrease between 16 and 20% in constant prices.

[6] Study available here: http://www.agri-outlook.org

[7]Source: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/agri-short-term-outlook-summer-2018_en.pdf

[8] Source: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/milk_en

[9] For updated figures see here: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/market-observatory/milk/latest-updates_en

[10] DG Agri estimates based on World Bank (https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/statistics/facts-figures/price-developments.pdf)

[11] Document available here: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/agricultural-outlook-2017-30_en.pdf

[12] Source: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/market-observatory/milk/pdf/market-situation-presentation_en.pdf

[13] Source: DG Health and Food Safety – Overview report – Welfare of Cattle on Dairy Farms, 2017, DG(SANTE) 2017-6241

[14] Source: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/milk/policy-instruments_en

[15] See here: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/01/29/skimmed-milk-powder-council-modifies-rules-on-public-intervention-to-help-the-market/

[16] Source: ZBIGNIEW Gołaś DOI: 10.5604/00441600.1245843 University of Life Sciences Poznań Problems of Agricultural Economics 3(352) 2017, 19-40

[17] With a linear causality between farms’ characteristics with their margin, except for cow herd size.