March 2021

Abstract

This paper aims to cast a light on the nexus between the profitability of rural livelihoods and biofuels within the EU. In doing so, it focuses on putting the deep and structural relationship between rural labour and biofuels into a data driven perspective to highlight what is rarely discussed: the low wages within the farming sector and the reality that without biofuels, this situation would be even worse.

Summary

- There is no plausible coherence in the positions of policymakers who simultaneously extoll higher minimum wages, argue that the EU should grow more food and malign biofuels—even though some would like to present it as a consensus position in Brussels. The only way to reconcile these positions in the European Green Deal is to re-evaluate biofuels based on actual 2020 data and then promote a gradual increase in biofuels.

- The role of biofuels in markets has been treated by researchers simplistically, much as minimum wage was for most of the last century. These simplistic approaches are not only wrong, but they are wrong for exactly the same reasons that the minimum wage arguments were wrong.

- Enough data now exists for a more mature approach to the role biofuels play in the economy.

- EU farmers earn on average €20k annually. Three quarters of all farms are family enterprises that have an even lower average income. This explains as well why farms have been abandoned at high rates in the last decade.

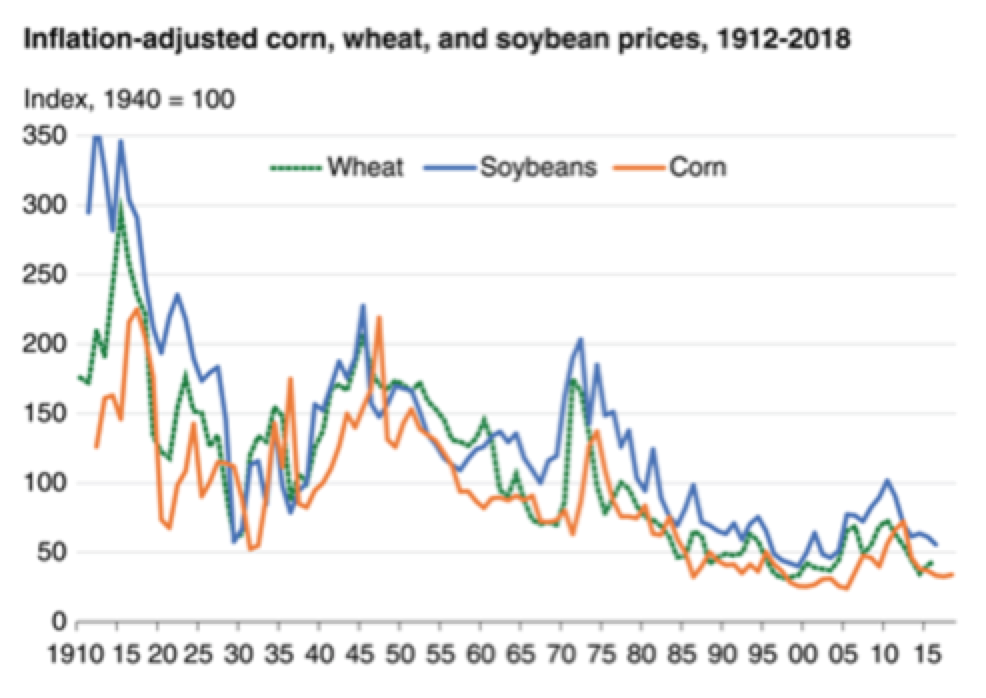

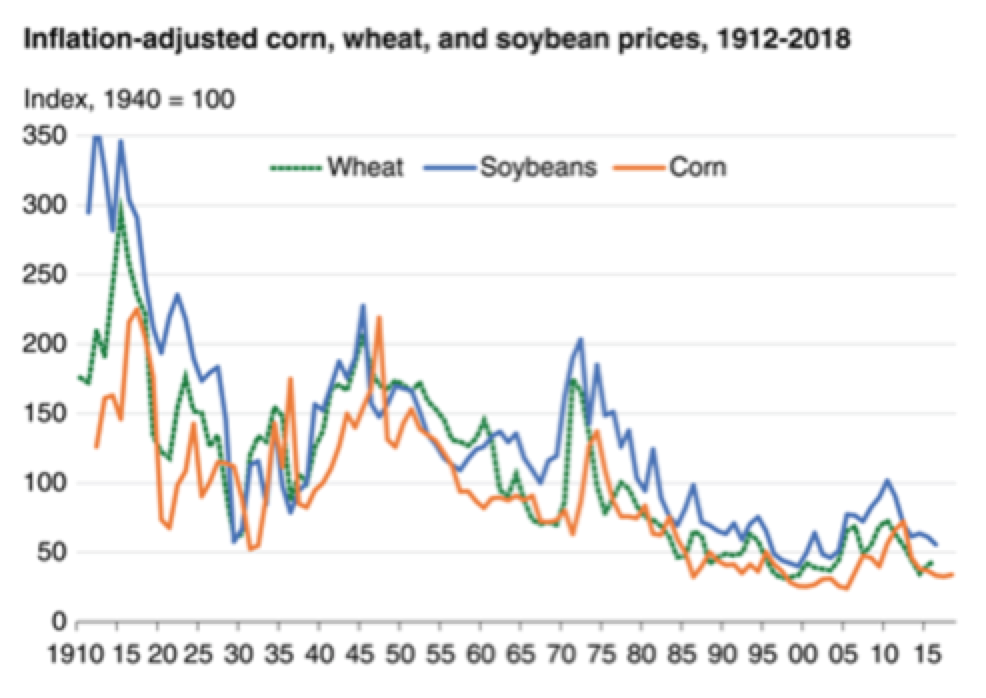

- The main reason for low farm incomes is the low market price of agricultural products. Real prices of corn, wheat, rapeseed, barley, rye, triticale, sugar beets, sunflower and soy have been declining since the 1950s. Productivity growth has not kept up with the decline in real prices.

- Since the average age of farmers in the European Union is between 50 and 60 and increasing, the rate of farm abandonment may dramatically increase through 2030.

- The way to improve farm incomes is to increase demand for farm products.

- Biofuels have in the past provided price support for basic agricultural products in the EU, without causing any harm to food market. Although not enough to reverse the trend of price erosion.

- As recognized by the Commission itself, earlier predictions of Commission policy makers for EU sourced biofuels in 2020, pointing to higher food prices or adverse land and environmental impacts, were incorrect.

- The Commission recognises as well the importance of EU biofuels to the economy, and to reducing GHG emissions

- An increase in biofuels use in the European Union to 2030 is the obvious choice to advance social, climate and economic priorities.

The paper first explains the recent evolution of farm profitability in the EU and point out that the EU has struggled to give meaningful answers to live up to its obligation on safeguarding a reasonable living for the European Union farmers. One significant contribution in this aspect is the role that EU biofuels play and could offer, hence the paper then proposes a policy direction to follow.

Evolution of farm profitability in the EU

European farmers struggle to eke out a living. One of the goals of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is to safeguard European Union farmers to make a reasonable living. Studies show that profitability in agriculture was and currently still is a major problem.

While there are indeed huge differences between the farm income of Member States or the various types of farming, some trends can be observed:

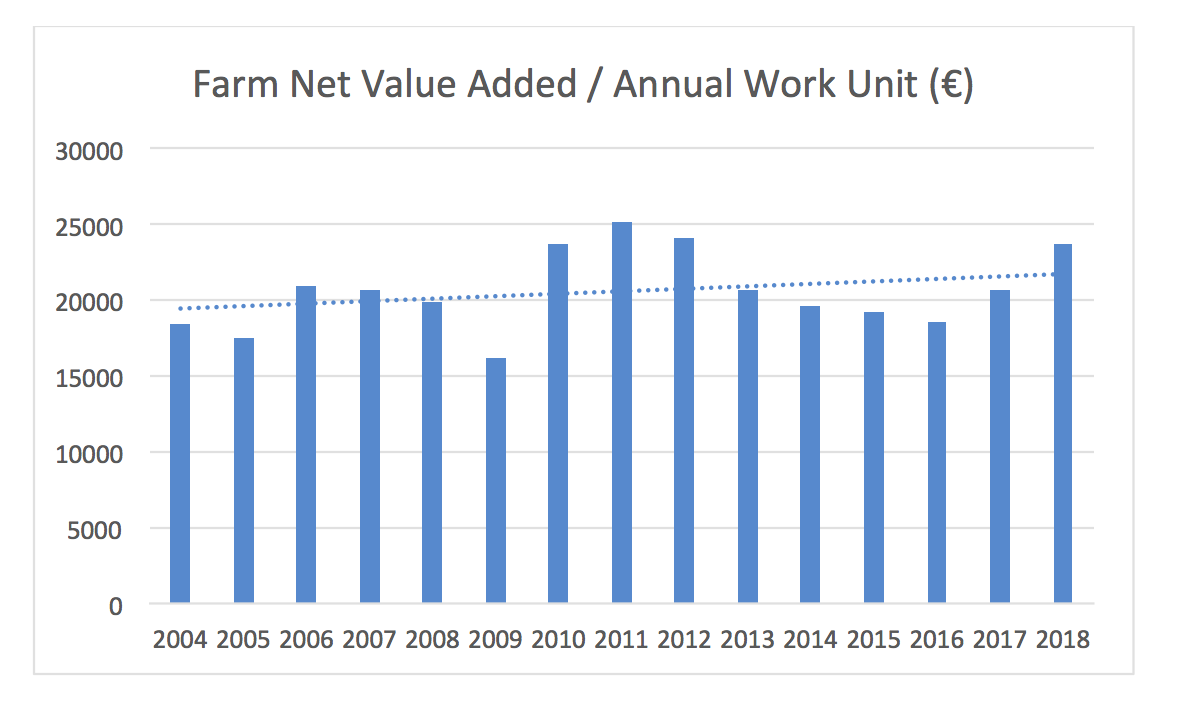

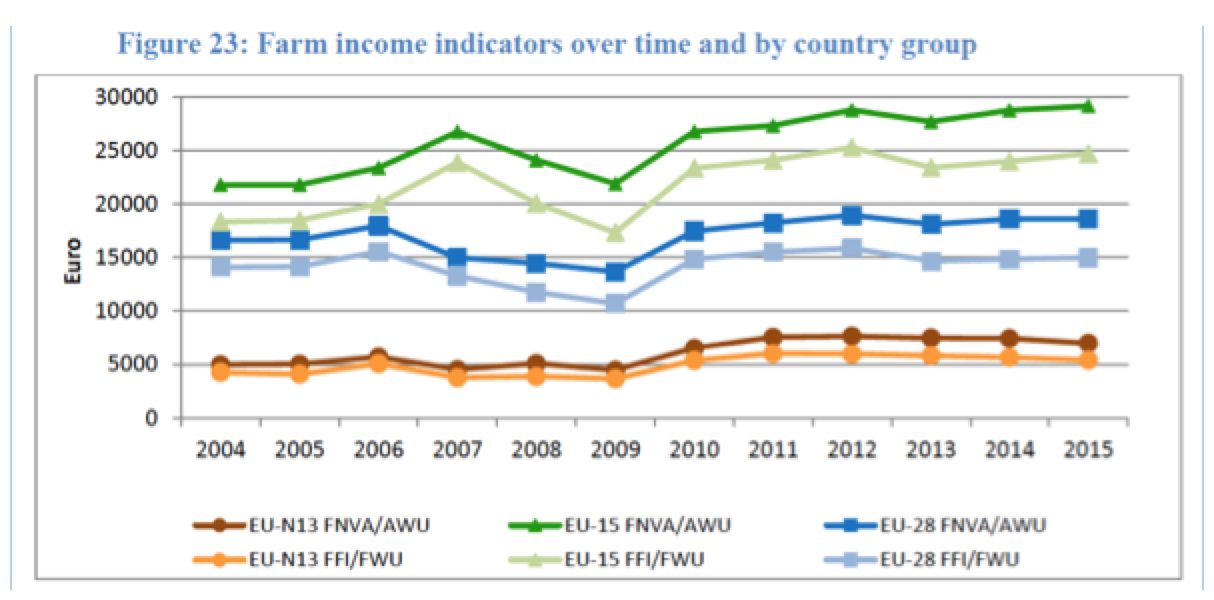

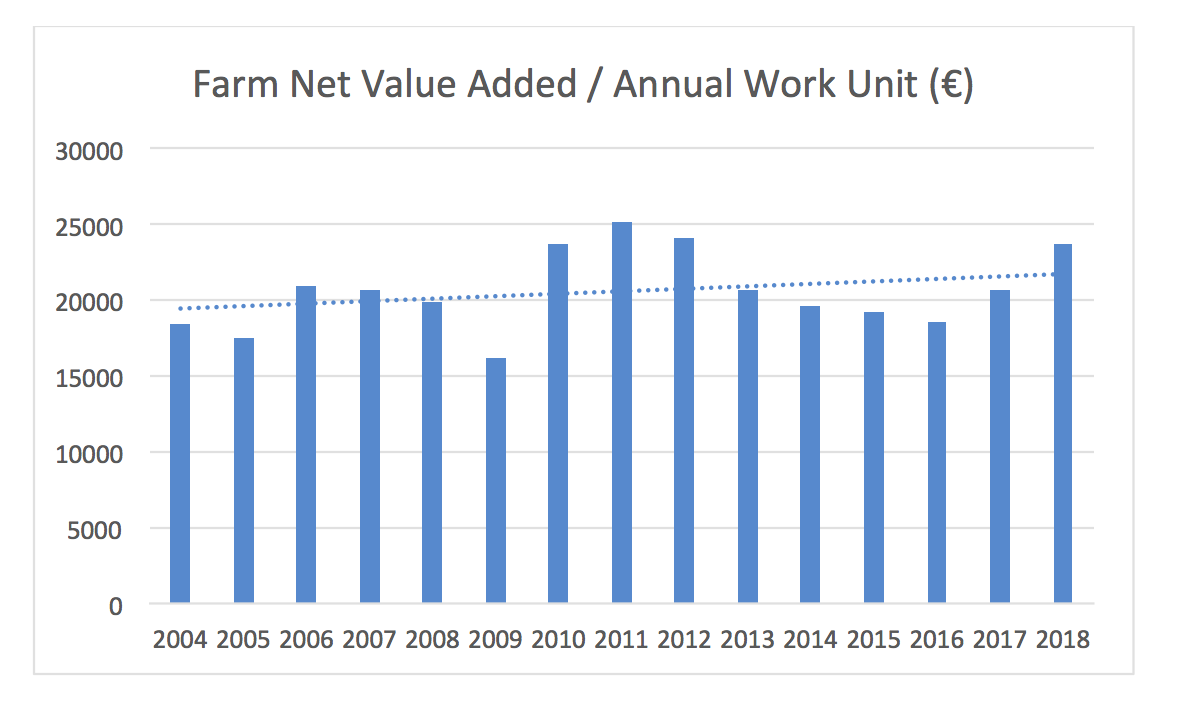

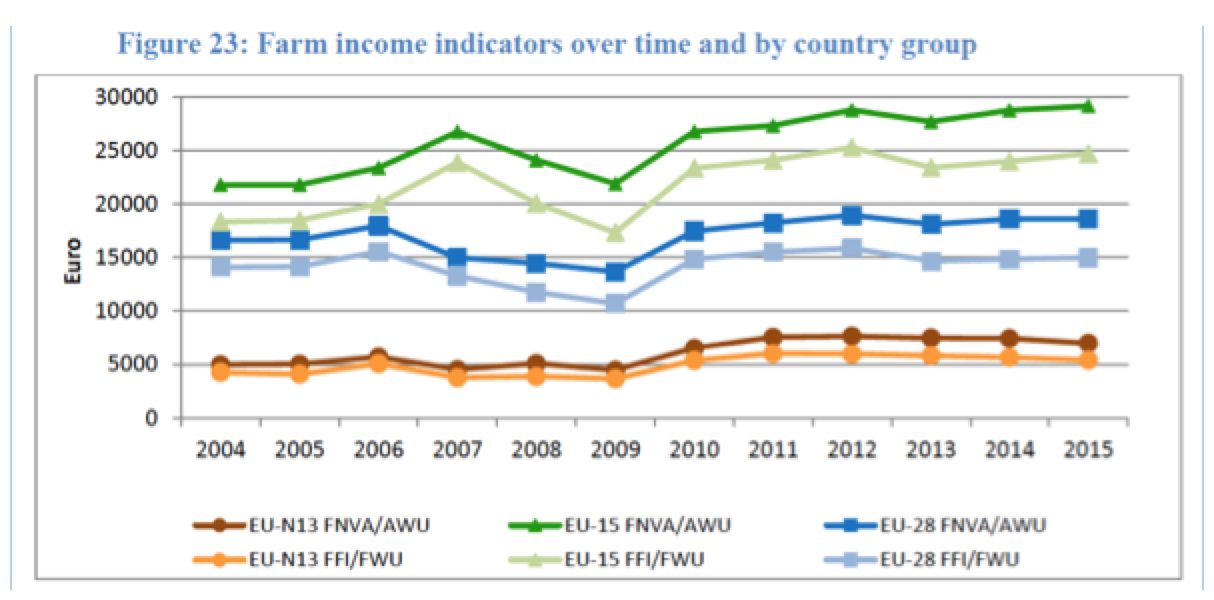

Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) provides sample farm data that is probably the best available on farm profits. A 2018 EU report based on FADN, “EU farm economics overview”, focuses on Farm Net Value Added (FNVA) as an indicator of profitability. FNVA is usually expressed per Annual Work Unit (AWU), which can be seen as a measure of labour productivity.

The chart below shows the evolution of FNVA, i.e. gross farm income minus depreciation costs. It is presented by labour unit, so differences in farm sizes are taken into account. Only field crops are included in the chart, albeit not much of a difference across farm types. It shows that the annual income per farmer in the EU has been about €20k.

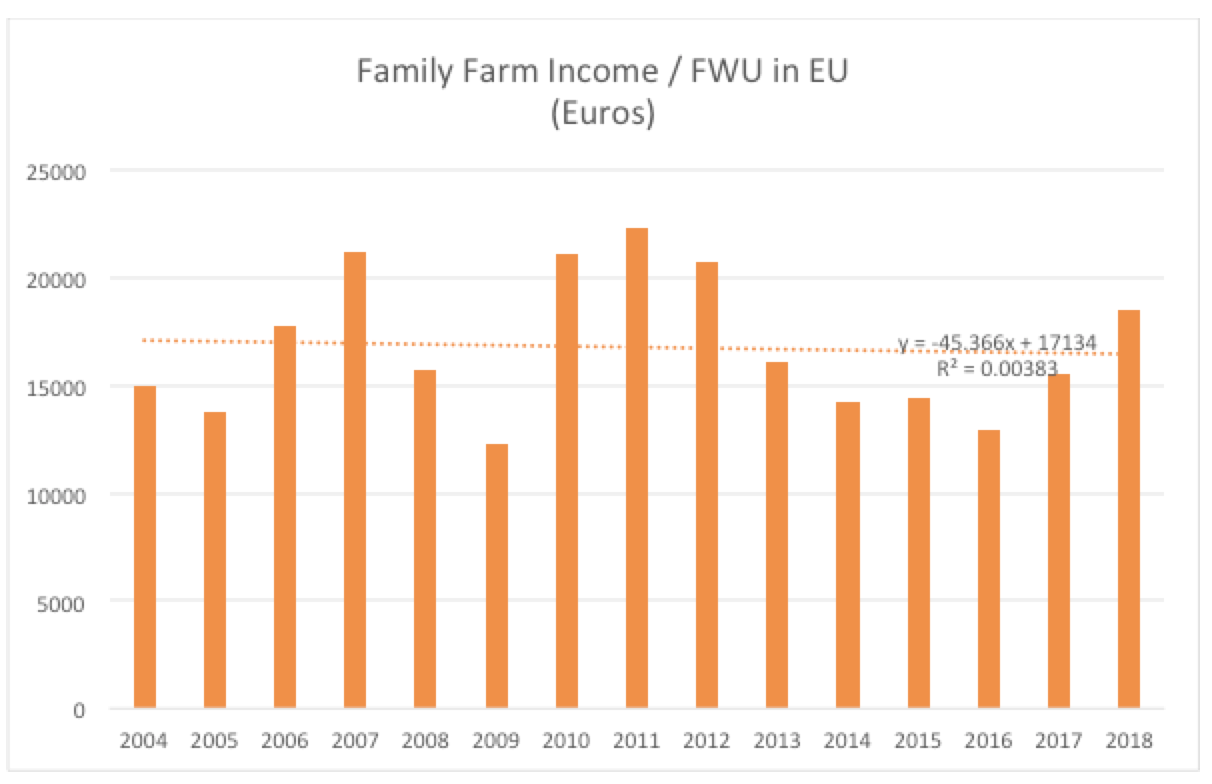

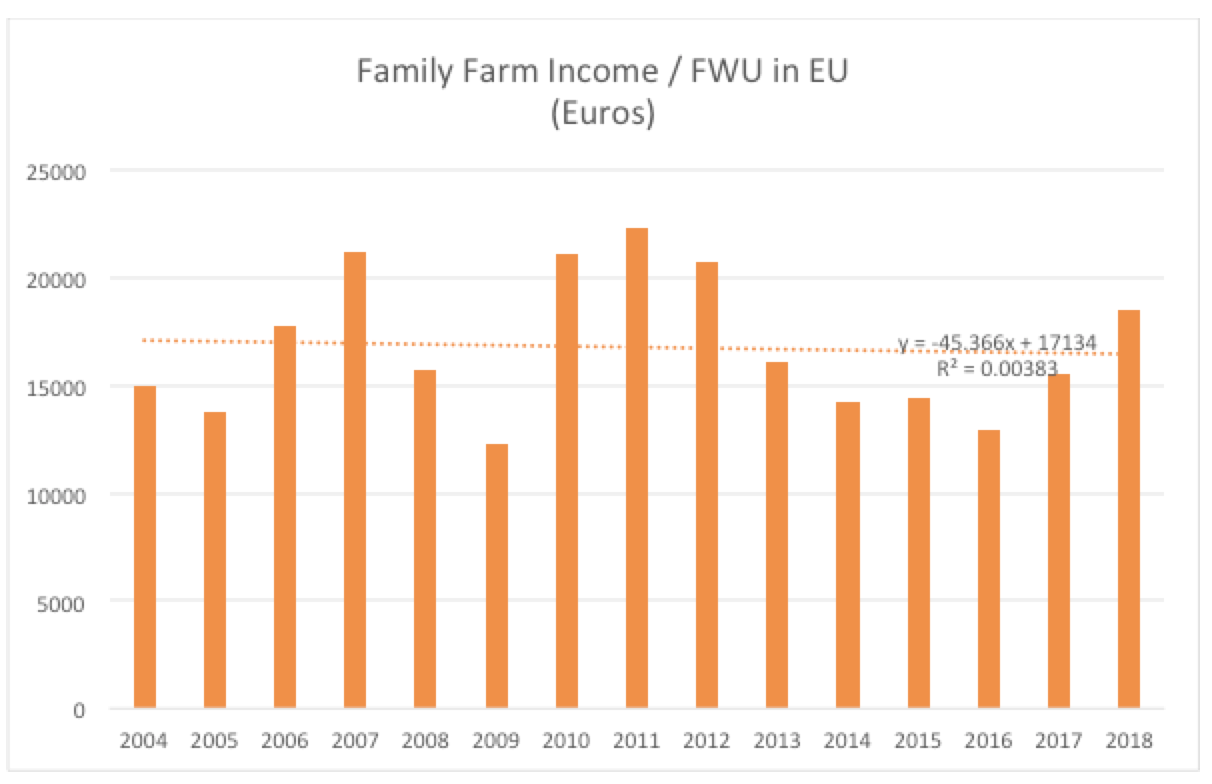

An alternative measure of agricultural income is Family Farm Income (FFI), as a high proportion of work in the agricultural sector (about 75%) is carried out by family members. FFI is expressed per family work unit (FWU), and is calculated by deducting from FNVA the costs of wages, rent, interest, and the opportunity costs of own capital, so that we arrive at the remuneration of family labour. At the EU-28 level, the average farm family income expressed per family labour unit (FFI per FWU) stood at €18.5k in 2018. Notably, between 2004 and 2018 FFI per FWU did not increase.

In comparison, the net annual earnings of an average working couple with two children were EUR 50 500 in the EU-27 in 2019.

Since an income of €15-20k is not an appealing prospect, it is no surprise that young farmers are few in number. Moreover, farm income is around 40% lower than non-agricultural income. Lastly, the farm income has been mostly flat in the past decade despite a decrease in the number of farmers and an increase in average farm size.

Source: DG AGRI, Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN)

The aging of farmers is a serious problem. The average age of farmers was 49.2 in 2004, but 51.4 years in 2014. In 2016, almost one third (32.8 %) of all farm managers in the EU-27 were 65 or over. Only 11% of farm managers in the EU were under 40.

Source: Eurostat

Without even mentioning the drastic effects of what climate change will bring or the economic downturn and business uncertainties caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, these indicators only lead towards one conclusion: a bleak picture regarding the future of the next farming generation and that thus farm abandonment may dramatically increase through 2030. In order to change this negative trend and overcome these challenges, farmers need reinforced tools to be able to be profitable once again.

A European Parliament study finds that ‘structural statistics for EU agriculture make it clear that many farmers (at least a third, and more if other members of their household are included) also have other gainful activities. National results where available show that other incomes not only raise the household income levels of farm families, but also add to its stability.’ In other words, many farmers rely on other incomes as revenue from farming alone is insufficient to maintain a decent standard of living.

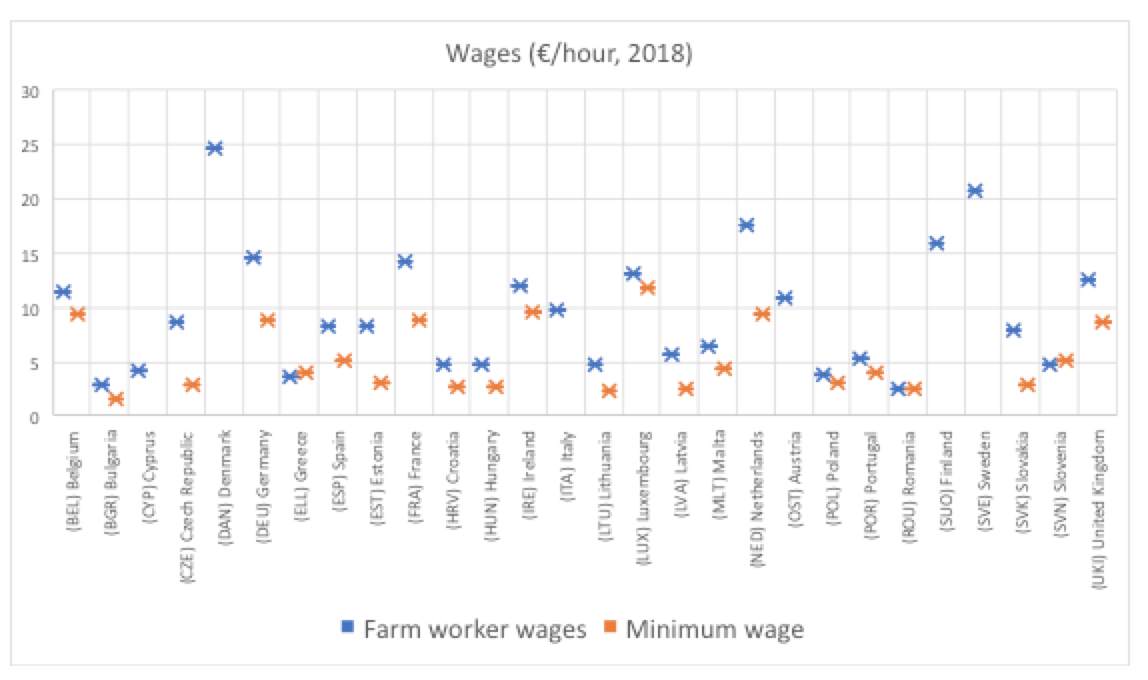

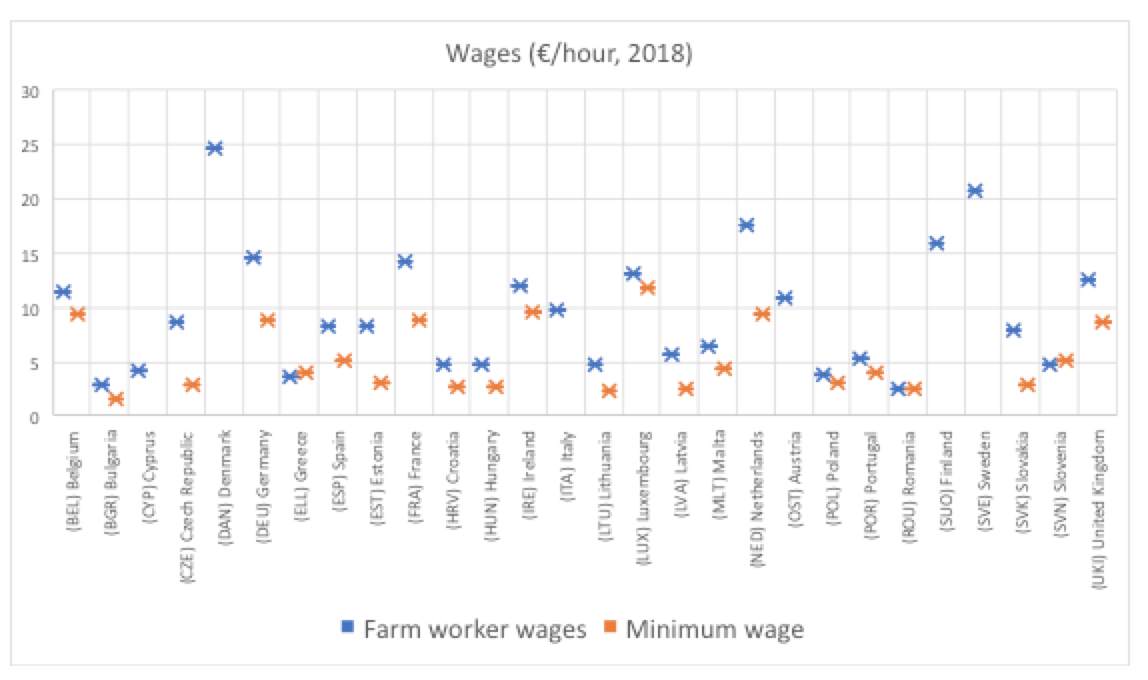

The EU Farm Economics Overview (2018) found that the average hourly wage of farm workers was €7.90 in the EU-28 in 2015. Eurostat reported €23.1 as the EU’s average hourly wage in 2017. Farm worker wages are close to the minimum wages in most EU countries (see chart below). In Greece and Slovenia, farm workers earned less than minimum wage in 2018.

Source: FADN and Eurofound

In short, farmers and their employees struggle to earn a decent living, and farming presents economically bleak prospects to a younger generation that has other options. This has all resulted in the fact that from 2008-2018 2.3 million farmers left the sector and were not replaced. Some of their land remained in agriculture through farm consolidation but a significant amount was just simply abandoned.

One must not forget the combined effect of stiffer price competition, rising costs and volatility plus public aids whose real value decreases each year.

Finally, taking into account the European Commission’s initial Common Agriculture Policy reform proposals it forecasted that farmers’ incomes are bound to drop by a staggering 14% (in real terms) in the next decade when the Farm to Fork Strategy is already considered to rearrange the status quo.

All this proves that farm profitability needs to be at the heart of agricultural policies if the true objective is to conjugate the revival of European rural regions. In that respect, coordination of policies focusing on farming, climate and energy policies is necessary.

Inflation-adjusted prices for corn, wheat, and soybeans and other basic agricultural commodities show long-term declines. Increased productivity in crop production underlies a general decrease in inflation-adjusted prices over the past century (see chart below).

Source: USDA

In conclusion the only way to improve farm incomes, other than subsidies, is to increase demand for the products that farms produce. Unless being able to hope for a reasonable living more and more farmers will decide to leave the sector. This would have a devastating impact on the countryside, as farmers won’t be there to deliver any more of their caretaking or public good services, which are not normally paid for by the markets.

The role of biofuels

On the other hand, crop-based biofuels offer a way to provide price support to farmers with declining incomes. Unsurprisingly therefore farmers and farming associations support biofuels in Europe.

Farmers find that conventional biofuels make it easier to manage agricultural commodity markets, which can help stabilise agricultural commodity markets and prices, as well as providing greater security for consumers and farmers. Farm Europe notes that biofuels produced from EU feedstock (mostly from colza, maize, sugar beet and wheat) generate at least 6.6 billion euros of direct revenue for EU farmers.

Even at their moderate volumes in the EU today biofuels have not actually increased agricultural prices. The 2017 EU Renewable Energy Progress Report finds that “EU ethanol consumption had negligible impact on cereal prices”. The report also notes that lower biofuel demand for vegetable oils was a factor contributing to the fall in oils/fats prices.

Arguably, without biofuels, demand for farm products would be even lower, further aggravating the situation.

As an Irish farmer representative put it “without the ability to make income farming goes nowhere and the next generation won’t be there”, stressing the pressure on incomes and the lack of markets to consume their products. In short, markets need to be preserved and created for farmers outside the Common Agricultural Policy’s subsidies.

As Copa-Cogeca, CEPM, FEDIOL and other farming associations stated producing biofuels from arable crops in the EU has opened up new agricultural commodity markets for European farmers. Biofuel production has encouraged investments on farm and into agricultural research, which in turn has allowed yields to be increased through improved techniques and new crop varieties. This is found to be beneficial for the production of food, feed and biofuels.

Further, European produced biofuels reduce by 13 MT dependency on imports of proteins used in animal farming (soy from the Americas), by supplying animal feed as co-product.

Moreover, jobs are created and maintained mostly in rural neighbourhoods – IRENA finds that 239 thousand jobs were supported directly and indirectly in the European Union by the production of liquid biofuels in 2018-2019.

Last but not least, biofuels have contributed more to effect transport decarbonisation than anything else over the past decade.

Policy direction to follow

Policy issues are not black and white.

A mix of over-simplified economic theory and improperly applied ideology has misled a plurality of EU policymakers to believe that crop based biofuels present no benefits, even though evidence in 2020 makes that position entirely indefensible. Moreover, the evidence in 2020 makes clear that whatever the right balance is for crop-biofuels use in the EU, current volumes are too little.

Extreme arguments have been mobilised, such as suggesting replacing all transport fuels with biofuels. However, business and industry, along with most policymakers, do not support these extremities. Moderation and context are sorely needed in the biofuels debate. This implies a profound change of mind of some influencers and decision makers and a change as well in the types of public actions. It is about leaving a world of dogmas and assumptions that have been flourishing for more than a decade in order to redefine an ambition based on science, pragmatism and the will to move forward together without stigmatizing each other but accompanying the progress and the necessary transitions.

An increase in biofuels use in the European Union to 2030 is the obvious choice to advance social, climate and economic priorities.

Without biofuels, farming in Europe is likely to continue to decline—resulting in job losses and the EU will miss its objectives of decarbonisation of transport notably.

As is the case for its agriculture as a whole, the EU shall not limit itself to a series of initiatives aimed at accompanying a slowdown for biofuels but it must focus on launching dynamic economic strategies within agriculture to boost investment across the EU.

The decade between 2020 and 2030 should be used to tap the potential in biofuels to strengthen farming, by providing a stable market outlet – making the prospect of farming more alluring to young farmers and thus enhancing the role of agriculture becoming a provider of a decarbonized economy.