As part of the process of enlarging the European Union to include Ukraine, Farm Europe has analysed both the weight and comparative competitiveness of Ukraine’s main crop sectors compared to those of the European Union.

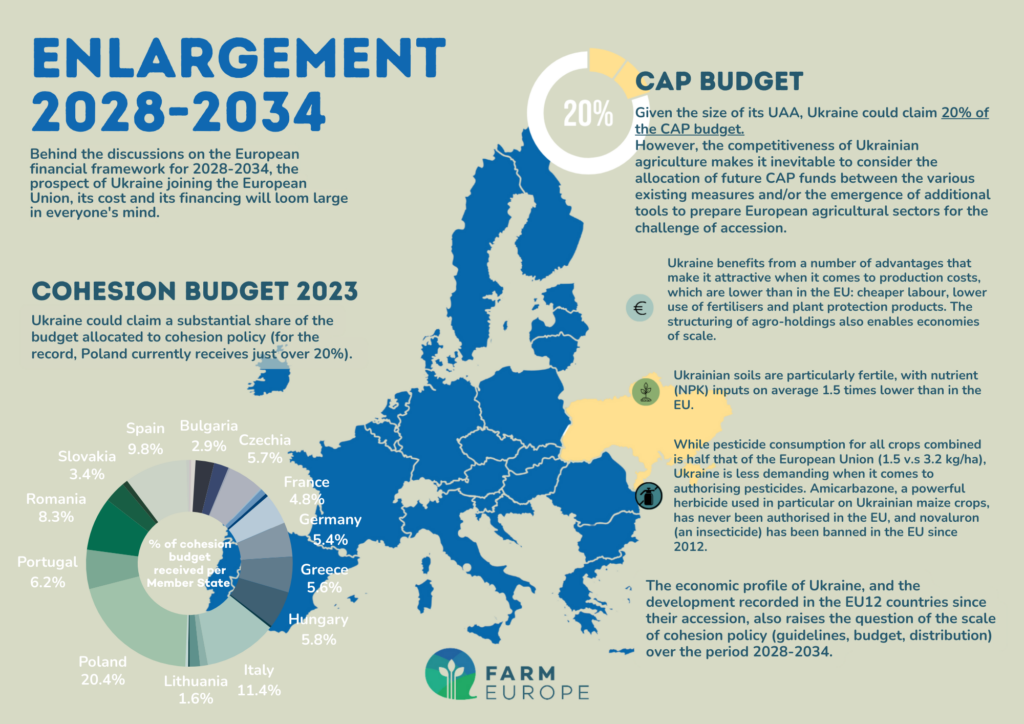

The difference in competitiveness ranges from 19% to 39% depending on the sector, with structural factors accounting for most of the difference. To this must be added the ‘carbon’ competitiveness conferred by the natural richness of Ukraine’s soils.

At a time when the steps and conditions of accession are about to be drawn up and the pre-accession programmes defined and launched, we feel it is important that objective data can serve as a basis to define the European Union’s roadmap, without bias or avoidance.

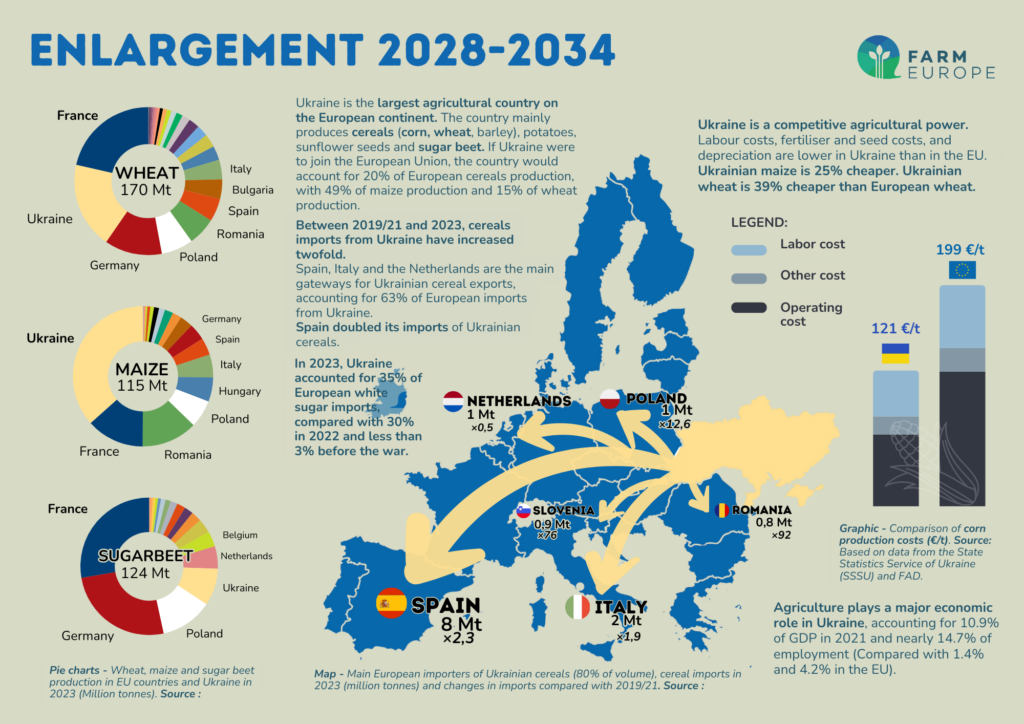

Ukraine & European Union: key figures for the main agricultural crops

In 2022, Ukraine’s utilised agricultural area covered 41.3 million hectares, including 32.7 million hectares of arable land (State Statistics Service of Ukraine (SSSU)). This agricultural area makes Ukraine the largest agricultural country on the European continent. 45% of the country’s surface area is made up of humus-rich, particularly fertile soils known as ‘rich’ chernozems.

Marked by its communist past, the Ukrainian agricultural sector is characterised by 110 huge vertically integrated agricultural companies, known as agro-holdings, which control all or part of the production chain (crop-livestock, processing, trade). These entities aim to maximize returns on invested capital, investing heavily in cutting-edge, large-scale equipment and the use of inputs. Twenty of these companies are estimated to control 14% of Ukraine’s Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA), and 57% of the UAA is farmed by enterprises of more than 1,000 ha. Agriculture plays a major economic role in the country, accounting for 10.9% of GDP in 2021 and almost 14.7% of employment.

Sugar

The organisation and competitiveness of the Ukrainian sugar sector is very different from that in Europe: agro-holdings, huge vertically integrated farms, cultivate 93% of the sugar beet area. The average cultivated area is 23,700 ha, 1,763 times more than in the European Union.

Ukraine has much lower labour and investment costs. What’s more, the presence of fertile soils means that fewer inputs are used on crops: up to 1.5 times less fertiliser than in the European Union.

The opening up of the European market to Ukraine has resulted in an influx of sugar, which has led to an increase in European stocks. Exports of sugar from Ukraine to Europe have increased by 230% between 2022 and 2023, with a forecast export capacity to the EU of 800,000 tonnes to 1 MT. The introduction of safeguard measures now limits exports for the time they are in force.

Detailed analysis for the sugar sector

Cereals

Cereal production is not as dominated by large farming structures as the sugar sector: 51% of production is carried out by structures of less than 1,000 ha. It should be noted, however, that 22% of production is carried out by companies with more than 3,000 ha.

If Ukraine were to join the European Union, the country would account for 20% of European cereals production, with 49% of maize production and 15% of wheat production.

Ukrainian cereal production costs are on average 30% lower than those in Europe.

For these reasons, grain imports from Ukraine have doubled between 2019/21 and 2023. The European Union has become a pillar of support for the Ukrainian economy, accounting for 51% of wheat exports in 2023, compared to 30% in 2021.

Detailed analysis for the cereal sector

Sunflower

While 58% of production is carried out by structures of less than 1,000 ha, companies with more than 3,000 ha account for 17% of production. In 2023, Ukrainian production alone was greater than the entire EU’s production. As such, if Ukraine were to join the European Union, the country would become Europe’s leading producer of sunflower seeds, as well as sunflower oil.

Ukraine has been the EU’s leading supplier of sunflower oil for around ten years now. The opening up of the European market to Ukraine has had no significant impact on the flow of sunflower oil from the country.

Detailed analysis for the sunflower sector

Rapeseed

Farms of less than 1,000 ha account for 73% of rapeseed production, but oil production is dominated by 5 companies which accounted for 92% in 2021.

In 2020, the cost of rapeseed production in Ukraine was, on average, 1.5 times lower than in France.

Compared to the 2018-2021 average, Ukrainian production of rapeseed and rapeseed oil has risen by 57% and 174% respectively. Similarly, exports grew by 37% and 170% respectively. If Ukraine were to join the European Union, it would become the leading rapeseed producer in the EU, accounting for 24% of seed production and 4% of oil and meal production.

The EU was already the largest importer of Ukrainian rapeseed products before the war.

However, imports of rapeseed have increased, and the EU now receives 93% of Ukraine’s rapeseed exports, compared to 83% in 2020/21.

(Click on the image to enlarge it)