Archives: Travaux

Post Type Description

Plan on Beating Cancer: more focus on education policies

February 3, 2021

The European Commission is about to publish its Strategy for Beating Cancer. The document that gives the political direction of the EU’s action in the fight against cancer is complete and takes into consideration the different phases of the diseases, together with the livelihood of the patient (survivors, carers, their families, etc.). It is a step in the right direction in the prevention of cancers and it will, hopefully, improve treatments and knowledge. Nevertheless, we would like to underline some point of reflection:

– Prevention: the strategy rightly points out that “prevention is more effective than any cure”, and that it is “the most cost-effective long-term cancer control strategy”, therefore, the plan “will raise awareness of and address main risk factors such as cancers caused by unhealthy lifestyles”. “Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan will give individuals the information and tools they need to make [the] healthier choices”, however, no concrete action is proposed (such as financing communication and dissemination campaigns, seminars, citizens engagements, and, most importantly, education). The strategy must not forget that education is the key element in every long-term vision plan.

– As in the proposed European Programme for Health (2021-2027), the plan does address diets and nutrition as a cause of cancer (and Non-Communicable Diseases at large). Nevertheless, for a more complete approach, the EU should reconsider more the role that diets play in health. It is of the essence for European and national policies to take the effects of what we eat on health seriously, without pointing fingers, but by disseminating scientific knowledge and involve active citizenship.

– The approach goes in the right direction when it addresses obesity in childhood, however, a simple revival of existing policies and actions that did not show the expected outcomes (such as the fruit and vegetable school schemes, because occasional and focusing on a small number of schools and children) will not do. At any rate, schools are indeed the place where healthy habits are to be formed; in this context, compulsory weakly hours of educational programs focused on health and lifestyles could be a more proper solution, as the strategy states: “measures in schools will also address health literacy to improve knowledge on the benefits of healthy nutrition”.

– On the proposed action to implement fiscal incentives/disincentives on food, studies [1, 2, 3] have shown the lower efficacy of this kind of policies, together with the risk of underlying social disparities. On this action, the Commission should run a thorough impact assessment and come with efficient proposals focusing on education, information, and tackling the issue of health-related to food marketed, notably of processed and ultra-processed food.

—

REFERENCES:

- Darmon et al. “Food price policies improve diet quality while increasing socioeconomic inequalities in nutrition” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2014, 11:66. Online source, consulted on October 22nd, 2020: http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/11/1/66

- Eyles et al., “Food pricings strategies, population diets, and non-communicable disease: a systematic review of simulation studies”, PLoS Medicine, 2012. Online source, consulted on November 4th 2020: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233915556

- Smed et al., « Differentiated food taxes as a tool in health and nutrition policy”, Food and resource economics institute, 2005

EAT EUROPE is the dedicated department of Farm Europe which aims to tackle the most sensitive societal issues, focusing on the role that institutional actors play in citizen’s health, analyzing and defining the tools that the EU and its Member States could implement in order to prevent their population from habits that could lead to unhealthy lifestyles. It reasons on science and efficacy, by gathering knowledge of people and focusing exclusively on the EU common good and its ability to deliver.

CAP REFORM NEGOTIATIONS: Commission hints for eco-schemes

January started the Portuguese presidency of the EU Council, with agricultural minister do Cèu Antunes defining the priorities of its mandate: conclude the CAP negotiations with Parliament, hoping to deliver more resilience for the sector and a transition to a greener architecture. On this last topic, the Commission published a document describing potential measures that Member State could include in the elaboration of Eco-schemes, given the fact that they have already started working on their National Strategic Plans (to be submitted to the Commission by the end of 2021). German Agriculture Minister started internal consultation with the Landers’ representatives. Moreover, on the discussion on the horizontal regulation, the Reserve for the CAP crisis support seems to be a difficult topic to overcome among negotiators.

full note available on FE Members’ area

TRANSPORT ENERGY & RENEWABLES IN THE EU – WHAT THE LATEST COMMISSION DATA TELLS US

SUMMARY

Demand for energy in transport rose 7% overall during the five years to 2020.

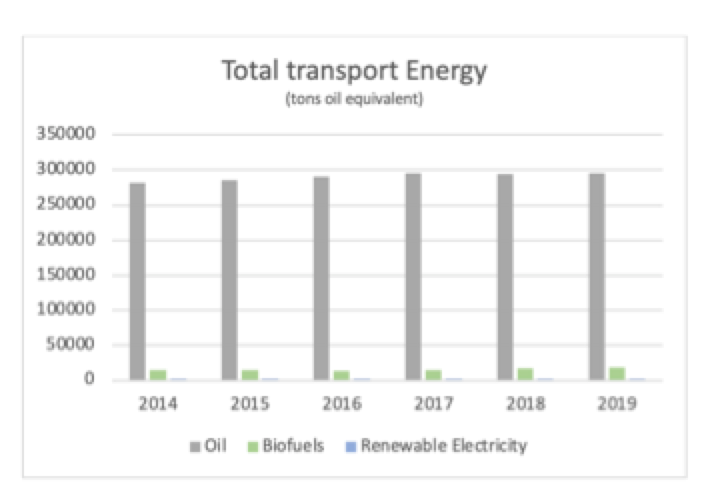

Oil maintains an overwhelming grip on the sector with a steady 94% share. The rest is biofuels with 5.6% and renewable electricity with 0.6%. Three quarters of the extra energy demand over the period was met by oil. 98% of renewables growth was biofuels.

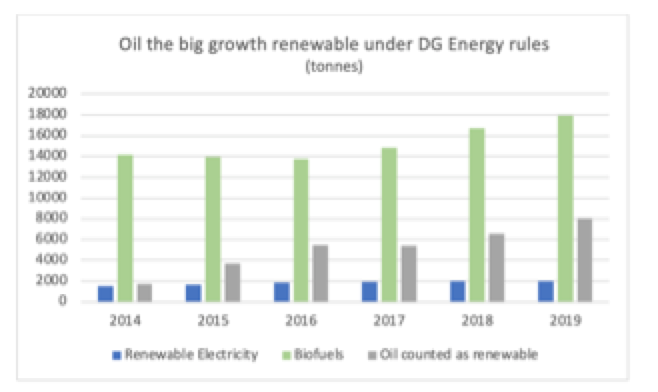

While the Commission highlights a figure of 8.88% for renewables in transport energy in 2019 this is not a true amount, including as it does, about 8.2 million tonnes of fossil fuel classed as renewables under the multipliers loophole of the Renewable Energy Directive. The true renewables figure was a more modest 6.3%.

Thus a sizeable portion of what is reported as renewables in transport energy consumption, and actually consumed, is in fact oil. From a reporting perspective it is vital that the Commission ceases to include oil in its headline figures for transport renewables as they have a grossly distorting effect.

In the interest of fraud prevention and better policy making it should report countries of origin of biofuels, especially for used cooking oil. It should report biomass types and origins of crop biofuels, especially in the case of palm oil, and it should report biomass types and origins for advanced biofuels in order to allow policy makers track and modulate the effects of their regulation.

Even with 8 million tonnes of oil counted as renewable, and a million or two tonnes of palm oil labelled as UCO it emerges from the data that growth in overall transport energy has run at twice the pace of growth in renewables over the last five years. Remove the dodgy oil and fossil energy growth beats renewables by a factor of three to one over the period.

For 2030 the European Commission has indicated a target of 24% renewables for the transport sector, and a similar level of cuts in carbon emissions. Yet it is difficult to see how the current trends can be so radically changed. Massive schemes will need to be put in place to support the deployment of renewable electricity. Palm oil biodiesel and UCO fraud will need to be brought under control. Multipliers should be eliminated as they simply represent another form of climate action indulgence, while completely distorting member state policies and behaviours. The European Tax Directive reforms of 2015 should be voted through, and soon. Biogas – the sleeping beauty of European renewables – needs to expand dramatically.

The EU needs to further the contribution of sustainable European biofuels, which could easily double by 2030. Positive policies should be put in place to allow that happen. If anything should be capped it is oil consumption, not sustainable European biofuels.

ANALYSIS

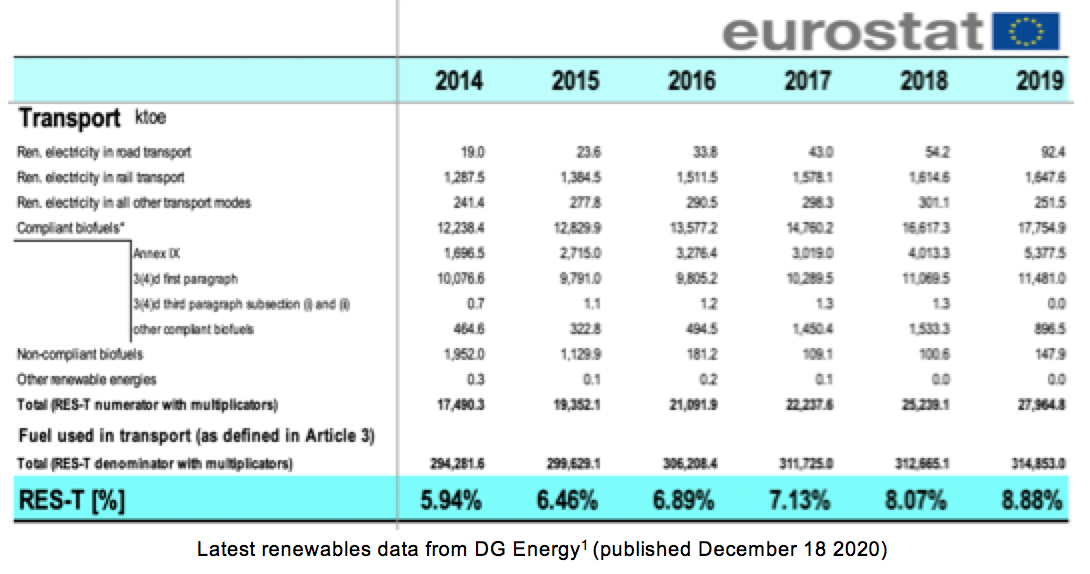

In December 2020 the European Commission published its latest data[i] for transport energy and renewables in Europe, as reported to it by member states for 2019 under the Renewable Energy Directive. Farm Europe reviewed the data and presents its findings here.

Steady rise in transport energy demand, half of it renewable

Demand for energy in transport rose 7% overall during the five years to 2020 according to the EUROSTAT data, with a near 1% increase in 2019. Vehicle numbers grew at a similar rate[i] with the EU fleet size expanding by around three million cars and trucks annually.

Oil maintains an overwhelming grip on the sector with a steady 94% share. The remainder was comprised of biofuels with 5.6% and renewable electricity with 0.6%. Three quarters of the extra energy demand over the period was met by oil. The trend towards renewables is improving somewhat: In 2019 the portion of additional energy demand supplied by oil was down to 45% with the remainder coming from additional renewable energy. Virtually all (>98%) of the additional renewable energy in 2019 was additional biofuels, with renewable electricity contributing the balance.

Oil treated as renewable, under RED multiplier rules

Under the RED method of adding up renewables in transport substantial amounts of fossil fuel enter the figures, creating some distortion in the reporting. So while the Commission highlights a figure of 8.88% for renewables in transport energy in 2019 this is not a true amount, including as it does, about 8.2 million tonnes of oil classed as renewable under the multiplicators loophole of the directive. The true renewables figure was a more modest 6.3%.

The multiplicators provision allows some renewables to be counted two or more times their actual values, when adding up the total, as an incentive for their development. It is not actual consumption of renewables that is reported.

The distortion is intensifying year on year, with fossil oil accounting for nearly 30% of the Commission’s reported renewables in 2019, up from 19% five years ago. Indeed there was bigger growth in oil classed as renewable by the Commission in 2019 than there was growth in actual renewable energy in the period. Oil labelled as renewable by DG Energy grew 70 times faster than genuine renewable electricity for instance.

Some countries lean on the practice more than others. In the UK for example, fossil oil accounted for 45% of the renewable energy in transport that it reported under Brussels rules for 2019. The country increased its consumption of multiple-counted used cooking oil biodiesel by 55% compared to the previous year. For every one of the 1.1 billion litres of UCO the UK put into its diesel, it declared a matching litre of fossil fuel as renewable.

Is Used Cooking Oil expansion legitimate?

Used cooking oil biodiesel (UCO) is by far the biggest example of multiple counted energy, and far from being a niche player it has become a dominating element on the distortive effects of multipliers.

Used cooking oil biodiesel grew 35% last year across the EU28 according to the data, and averaged 44% annual growth since 2014. Consumption reached 4.1 billion litres in 2019, up from 517 million in 2014. While the UK, Germany and the Netherlands accounted for two thirds of total UCO demand in 2019, France, Ireland, Portugal and Spain accounted for another 20% between them. Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands were the biggest per capita consumers of UCO diesel in 2019, with Ireland at 38 litres per person and Luxembourg at 60. These are large numbers if one considers that a country with a mature UCO collecting infrastructure will collect at most 4 or 5 litres per annum domestically while most countries in the world collect one litre or less per person, or quite commonly, none at all.

The majority of EU member states sought big increases in UCO utilisation last year, with the UK, Sweden, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Netherlands, Hungary, France, Czechia and Croatia all participating in rapid expansion. Only Germany bucked the trend, with a 23% drop in UCO consumption.

The total amount of UCO consumed in EU biodiesel in 2019 was four times what is collected domestically from Europe’s catering sector. Hence the bulk of it is imported from jurisdictions where Europe has no powers to investigate or prosecute operators tempted into the fraudulent substitution of UCO with lower cost and readily available bulk palm oil. DG Energy allows any biodiesel declared as UCO to be counted as UCO under the directive, without requiring physical audits or inspections of the supply chains and without any form of supply chain risk assessment. UCO fraud is financially rewarding, easy to get into and largely free of interference by governing bodies. UCO fraud represents a major lost opportunity to Europe’s farm sector, which produces highly sustainable and effective biofuels and would have the capacity to produce more under a smart and fair regulatory system.

DG Energy does not[i] publish country of origin data for the UCO consumed as biofuel under the renewable energy directive. However that data is provided to them by law so could be published, and it would be of great interest if it was. It would allow stakeholders identify and assess situations involving countries listed as sources of UCO in quantities that are greater then their UCO collection infrastructure would allow in reality.

To take one example, Malaysia, in addition to being the world’s second largest producer of palm oil, is an important supplier of UCO to Europe’s biodiesel industry. The UK and Ireland – in contrast with DG Energy – do publish[i] the countries of origin of the biofuels they consume. Malaysia was the origin of 90 million litres of the UCO used in Britain and Ireland in 2019. If Malaysia is the origin of similar volumes for the rest of Europe then its total contribution to EU UCO demand amounts to six or eight times its capacity for genuine UCO collection. The implications are clear: under weak regulation the UCO gold rush is likely as much about palm oil as genuine UCO, with British, Irish and other EU consumers unwittingly burning palm oil in their diesel vehicles instead of genuine waste cooking oil.

Advanced biofuels

The volume of advanced biofuels in the renewables mix rose about 17% in 2019 to just over a million tonnes of oil equivalent, contributing 0.3% of Europe’s transport energy and 5.3% of renewable energy in the sector. Growth in advanced biofuels in 2019 was about seven times greater in absolute terms than growth in renewable electricity but it was three times lower than crop biofuels growth, five times lower than UCO, and eight times lower than the fossil oil counted as renewable by DG Energy under the multiplicators loophole.

Advanced biofuels are made from materials contained in a list compiled by DG Energy – loosely intended as residues and co-products from industry and agriculture – and have for the last decade been strongly promoted by DG Energy. In addition to being double-counted like UCO, there is an obligation on member states to raise consumption to 1.75% of their transport energy needs by 2030, or about six times current average rates. DG Energy has also provided around half a billion euros in grant aid to the sector in the last decade, in particular for the production of biofuels from materials such as straw, with limited results showing up in the Eurostat data thus far.

Over 90% of advanced biofuels are consumed in just five member states: Finland (36%), Sweden (23%), UK (21%), the Netherlands (8%) and France (4%). Indeed most member states use little or no advanced biofuels, making their targets for 2030 quite challenging.

All of the 2019 increase of 150 thousand tonnes was attributable to Finland (45%), the Netherlands (30%), and Sweden 15%), with small rises seen also in France and Germany. Virtually all advanced biofuels in Europe come from just two of the seventeen types allowed in the directive: Industrial waste and forestry waste, with the industrial waste accounting for over 80% of it. Industrial waste is a broad category and it would be helpful for policy makers if DG Energy were to report more precisely what raw materials and source countries are involved.

Some stakeholders are concerned that without reform of the Commission’s regulatory competencies and procedures, the opportunities and incentives for fraud seen in UCO are transfering to advanced biofuels as the sector grows, with operators tempted to game the system both outside and inside Europe.

Crop biofuels

Crop biofuels are by far the largest category of renewables in the EU transport system, according to the data, accounting for a steady 3.5% of total transport energy over the past five years, and for around 60% of all renewable energy. In volume terms crop biofuels expanded 3% annually over the five year period, to reach 11.5 million tonnes of oil equivalent in 2019. The low growth in crop biofuels is attributable to the Commission’s decision to limit their role in renewable energy even though, in the case of domestically sourced crop biofuels, they are demonstrably better for the climate than increased use of oil, represent the lowest cost means of carbon emissions abatement and could be expanded with considerable benefits for Europe’s rural economy and food sector.

For such an important contributor to climate action in transport, to rural economic development and to protein feed security there is little detail in the data released by the Commission. There is no breakdown in the data to distinguish between domestically produced bioenergy and imports, or between the various types of biomass used.

Critically, the Commission omits to provide data on diesel made from palm oil, which it continues to allow under the legislation despite the environmental harm and carbon emissions associated with palm oil expansion. In fact the Commission allows low cost palm oil compete directly with highly sustainable domestically sourced crop biofuels from traceable European agriculture. This lack of feedstock and source country data is a grave omission as it obscures the situation, preventing policy makers from making accurate assessments.

Biogas in transport

Just 1.6% of renewable bioenergy in the EU transport system in 2019 was contributed by biogas, coming to 279 thousand tonnes of oil equivalent, or 0.1% of all transport energy. Biogas development, though coming from a low base, was positive, with around a 45% annual increase over the five year period. According to the data, the seven countries involved were Sweden (39%), the UK (27%), Germany (20%) and the Netherlands (7%), with Denmark, Estonia and Finland accounting for another 6% between them in 2019. In the case of the Netherlands all of its transport biogas was delivered through the natural gas grid, whereas in the other six countries it was directly fuelled. Italy also uses biogas in its transport system, and has enacted major legislation to support biogas in transport, but has not yet provided consumption data for EUROSTAT.

Biogas is seen by many energy experts as a highly effective means for enlarging the share of advanced biofuels, and of bioenergy and renewables generally. It can be readily produced from virtually any type of biomass and it can be consumed directly as heat and power, distributed through the existing natural gas grid or converted to electricity and distributed through the electricity grid. For a major scale-up to happen however one would need a common EU certification scheme, alignment of national support schemes for production and consumption and barrier-free cross-border access to those schemes. The current patchwork of incompatible national systems is a great barrier to sector development.

Electric cars

Renewable electricity in road transport in 2019 accounted for 0.03% of transport energy. This is up from 0.01% five years ago, but is still a low base and far from being a significant contributor to the 10% renewables target for 2020. In volume terms in 2019 renewable electricity on the road grew by the equivalent of 38 thousand tonnes of oil or enough to displace the fossil energy of about a hundred thousand conventional cars. The total EU28 fleet grew by 30 times that number – about 3 million vehicles – in the same period, indicating that renewable electricity has a way to go yet, to impact the trend in fossil energy consumption in the sector.

Overall, renewable electricity in transport, including rail, has hovered around 0.6% of total transport energy over the five year period to 2020.

The data shows that renewable hydrogen and synthetic fuels have yet to make a contribution to the energy mix.

Outlook for 2030

From a reporting perspective it is vital that the Commission ceases to include oil in its headline figures for transport renewables as it has a highly distorting effect. In the interest of fraud prevention and better policy making it should report countries of origin of biofuels, especially for used cooking oil. It should report biomass types and origins of crop biofuels, especially in the case of palm oil, and it should report biomass types and origins for advanced biofuels in order to allow policy makers track and modulate the effects of their regulation. The data should be released within three months of the end of the reporting period, and not a year later as is the current practice. Indeed the data should be released in quarterly cycles as done in the UK.

Even with 8 million tonnes of oil counted as renewable, and a million or two tonnes of palm oil potentially labelled as UCO it emerges from the data that growth in overall transport energy has run at twice the pace of growth in renewables over the last five years. Remove the inappropriate fossil fuel and fossil energy growth beats renewables by a factor of three to one over the period.

To nudge things in the right direction in 2021 oil consumption, which is currently subject to no limits, should be capped, and ideally its share of transport energy should be cut by some obligatory portion each year, even if only a percent or two.

For 2030 the European Commission has indicated a target of 24% renewables for the transport sector, and a similar level of cuts in carbon emissions. Yet it is difficult to see how the current trends can be so radically changed. Massive schemes will need to be put in place to support the deployment of renewable electricity. Palm oil biodiesel and UCO fraud will need to be brought under control. Multiplicators should be eliminated as they simply represent another form of climate action indulgence, while distorting member state policies and behaviours. The European Tax Directive reforms of 2015 should be voted through, and soon. Biogas – the sleeping beauty of European renewables – needs to expand dramatically. And in order to further the contribution of sustainable European biofuels, which could easily double by 2030, there should be positive policies put in place to allow that happen.

—- Analysis by James Cogan for Farm Europe.

References, endnotes

[i] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/energy/data/shares

[i] https://www.acea.be/statistics/article/size-distribution-of-the-vehicle-fleet

[i] https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/case/en/57742

[i]https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/renewable-fuel-statistics-2019-final-report; www.nora.ie/

WHAT IS IN THE BREXIT FINAL ACT FOR THE EU AGRICULTURE

The negotiation of a post- Brexit Trade Agreement with the UK has finally been concluded at the eleventh hour, after years of up and downs. Farm Europe has from the outset closely analysed the consequences of Brexit, and raised the attention of the sector and decision-makers to its large impact.

Our assessment is clear: the deal reached is pretty much the best possible outcome, although the very best would have been not to have Brexit in the first place. More on it at the end.

The Trade Agreement delivers across the board duty and quota-free trade for agricultural products. As the EU enjoys a hefty trade surplus with the UK this is indeed a good outcome.

On sanitary and phytosanitary rules, each side must respect the other’s rule when exporting.

On organic products, an equivalency agreement was reached.

On the very technical but equally important issue of Rules of Origin, key to preventing “triangular trade” and that the UK could become a platform to export third-countries products to the EU, most products are covered by the “wholly obtained” rule. This means that the products exported from the UK and that benefit from duty free access to the EU, must be produced in the UK without any significant content from third countries origins. Meats, dairy, cereals, starch, wines, are well covered by this rule. On processed products, the sugar content has in some cases more leeway, but as the UK has kept a high border protection we do not anticipate any significant problems.

Thus the integrity of the EU’s single market is well preserved.

The sole area where a broad agreement does not seem to have been reached is on the recognition of Geographical Indications, although there is some language as to possible further talks, which we would encourage.

To conclude, we have good grounds to congratulate the Commission, in particular the chief negotiator Michel Barnier and his team.

But let’s not forget that Brexit, even with a good Trade Agreement, will bring more costs and red tape linked to customs procedures; and increased competition in the UK market for our exports, as the UK has the freedom to negotiate Trade Agreements with third countries. Also, the risk of regulatory divergence in the future is real, it works both ways, and might negatively impact free trade.

The real impact of Brexit in our agriculture trade balance with the UK will take a few years to show-up, as the UK opens-up gradually to highly competitive third countries.

Although the Trade Agreement is the best possible, and we anticipate its ratification, our agri-food sector should not waste time to prepare for more competition. The CAP resources should without delay be mobilised to support improving the economic productivity of farming, whilst improving its environmental credentials.

Mobilizing the European Agricultural Recovery Fund for an accelerated transition towards a double-performance European agriculture

Precision agriculture provides farmers and livestock farmers with solutions adapted to their context. Data from sensors, cameras, satellites and meteorological stations are processed by algorithms that use Decision Support Tools (DST) to provide advice on the most relevant actions that can be taken.

The use of these tools ensures better input efficiency at the farm level. The latter are adjusted to the quantified needs of crops and animals while ensuring optimal yields. They are crucial tools in the transition of European agriculture towards a dual-performance agriculture: more economical in terms of inputs, taking care of the environment, and more economically efficient.

Digital agriculture also has the potential to simplify the administrative burden, both in respect of the implementation and control of CAP measures, and in respect of the data entered by farmers.

While studies highlight the benefits of such tools, the transition from the “research” phase to the agricultural sphere is still slow. To date, digital agriculture remains poorly democratized.

In addition, there are other main obstacles: the cost of these technologies, the fear that such long- term investments could quickly become obsolete.

However, in view of their economic, social and environmental benefits, it would be urgent to extend within the European Union the use of precision farming tools in crop production and the use of sensors and robots in animal husbandry.

The European Union must be an actor in the democratization of these tools, making them accessible to all farmers and livestock breeders whatever the type and size of their farms, their farming practices and their backgrounds.

Mobilizing 60% of the recovery plan to support innovative precision investments in agriculture in 2021 and 2022 will allow a special plan of 10 billion investment for an accelerated transition of European agriculture towards double performance. The investments of this plan could be supported up to 53% (share EU recovery fund 90%, 10% counterpart Member State), mobilizing 4.8 billion of the 8 billion of the said recovery plan.

The additional 3 billion from this recovery fund should be allocated, in synergy, to actions for skills acquisition and promotion of European products.

***

What are the incentives for an accelerated transition?

While €8 billion will be added to the financing of the second pillar of the CAP to relaunch the agricultural sectors, a relaunch to be carried out in coherence with the Green Deal objectives, these funds should be used in a targeted way, to really prepare the future and the rebound of the European agricultural sectors.

This implies giving priority to the funding of double performance transition investments, as well as measures to increase farmers’ competence in innovative techniques, to strengthen the structuring of the sectors and the promotion of European products.

The objective would therefore be to devote at least 5 billion euros of this allocation to support investment in precision agriculture in 2021 and 2022, in addition to the “investment” measures that will be implemented in the framework of the reformed CAP from 2023 (and those pursued during the transition period).

These 5 billion euros would constitute a decisive incentive for a special plan of 10 billion euros of investments in order to widely spread the use of DSTs on all European agricultural surfaces and to accelerate the accessibility of digital tools to livestock farms.

This change will lead to substantial savings in inputs, which will ensure greater sustainability and profitability of European production, an operational response:

– to citizens’ expectations regarding the environment, food quality …

– and to the imperatives of cost competitiveness, but also of promoting quality approaches.

These investments will have to be reasoned in different ways in order to be adapted to the diversity of farms. While farms above a certain size can make the investments alone, it will be appropriate to encourage collective investments in other cases, particularly in regions where farms may be smaller. Investments within the framework of cooperative, CUMA or of a third body, such as GAIA in Greece, should be used to their full potential as soon as they prove their effectiveness. The financing of coordination between producers, as well as technical support and equipment maintenance can and should be carried out by cooperatives. The traceability of the final products and the treatments provided to them should also be ensured by them.

Crop production:

Digital tools related to crop production can be classified into 5 levels according to their degree of precision, the equipment required and their cost. The use of precision farming tools (sensors, weather stations, satellite images, cameras, DSTs for input management) are present at each level. Weather stations require an investment of between €400 and €2,000 (Weenat, 2020). Some DSTs are free of charge. Those that prescribe the quantities of inputs to be applied from sensors and satellite images of crops have a maximum cost of €20/ha/year (Farm Europe, 2019).

– The first level, the most accessible, consists in using the information given by these tools to adjust the applications to the scale of a set of plots with the same pedoclimatic conditions and phytosanitary risks. The second level consists in adjusting the inputs at plot scale.

– From the third level onwards, in field crops, these tools are associated with modulation tools. These include precision sprayers, which are more expensive. The most accessible ones cost around €3,000. They are connected to a needs mapping service. Sprayers that modulate doses based on data from on-board cameras can cost more than €40,000. Modulating nitrogen doses ensures fertilizer savings of between 4 and 47% depending on production and environments. At the same time, it maintains or increases yield by up to 10%. The financing of such a sprayer can be done over 5 to 10 years. A saving of 11 to 90% is noted, depending on the case, concerning pesticides (herbicides, fungicides and insecticides). An increase in the gross margin from 7 to 38€/ha/year is possible.

Machine Guidance (MG) and Controlled Traffic Farming (CTF) complete this level, raising the precision of the actions carried out. These technologies make it possible to avoid crossing trajectories during treatments and to gain in precision at the intra-plot scale. Their cost varies from around €1,300 if the tractor is already equipped with GPS. It can go up to €50,000 for those with the most options. MG saves 2% on seeds and fertilizers, 6.32 to 10% on fuel and 6.04% on labor. It increases the gross margin between €38 and €612/ha/year. CTF complements the MG with the analysis of itinerary data and treatments from previous years. It saves 3 to 15% in fertilizers, 25% in pesticides, 25 to 70% in fuel and 70% in labor. A 15% increase in yield has also been observed. Increases of 40 to 80% in nitrogen efficiency have been recorded, increasing the gross margin from 57 to 115€/ha/year (Balafoutis et al., 2017).

– Levels 4 and 5 add to the tools of the previous levels robotization as an alternative to pesticides for the management of bio-aggressors (weeds, diseases and pests) as well as precision irrigation. The aim of robotization is to ensure that no more fertilizer and pesticide residues are detectable. Input adjustment takes place at the plot level in level 4 and at the plant level in level 5. Weeding robots cost between €25,000 and €80,000. They allow a reduction in pesticide quantities of 20 times compared to standard protection. They also reduce fuel use and working time.

Precision irrigation allows the amount of water irrigated to be adjusted to crop needs, soil moisture and weather forecasts. The most advanced systems can automatically trigger irrigation if those parameters are below a certain threshold. Flow controllers for pivot irrigation systems are the most affordable starting at €1,300 and pivot control irrigation management systems can cost up to €35,000. Drip irrigation costs around €40/ha. Savings of up to 34% are observed depending on the irrigation system. Their effect on yield is more contrasted, ranging from a reduction of 18% to an increase of 31%. Thus, input efficiency ranges from -12% to 97% for pivot control systems. Water savings of about €30/ha/year have been observed in the UK (Balafoutis et al., 2017). It is around the Mediterranean area that precision irrigation has the greatest potential. Water and energy consumption are reduced by 10-14% on average (FIGARO Irrigation Platform, 2016). In Greece, the net benefit can be as much as €480/ha for a cotton crop (Balafoutis et al., 2017).

Livestock:

Precision livestock farming is based on the use of sensors and robots.

Sensors can be on the animals to monitor their health (metabolic disorders, infections, lameness, udders, heat, pregnancy and calving). GPS can be used to monitor the location of the animals. These checks can be carried out using collars that cost around €120 per unit, plus €4,000 for data storage and interpretation and €180 in annual costs. These on-board sensors can save up to €100 per cow, increase productivity by up to 30% and reduce working hours by up to one hour per day (IDELE, 2019; LITUUS, 2019). Feed storage and quality can also be assessed, as well as the composition of the milk. Milk analyses can be used to anticipate infections, heat… A farmer will detect 50 to 55% of heat, while an automated detector will detect 50 to 99%. The anticipation linked to these analyses allows a gain of around €2,000 (Huneau & Gohier, 2017).

Robotization makes it possible to simplify milking, cleaning of stables or straw and feed distribution (mixing, quantity of feed distributed, number and time of passage and scraping of refusals). A feeding robot, preparing the mixtures and distributing the rations costs around €230,000 for 150 dairy cows. This type of robot can be financed for 12 years and amortized in 15 years. The annual investment cost is between 25 and 44% greater than for a tractor and a mixing machine, with a saving of almost 50% in maintenance costs and charges, compared to the latter. Similarly, a reduction of 15 to 20% in the workforce is observed. In the end, some studies point to an annual saving of almost 60% compared to the use of a tractor and a mixing machine. Other studies estimate an increase in production costs of €6,097/year but a saving of 400 hours of work (Autellet, 2019).

A milking robot costs around €120,000 for 80 cows. Although they reduce working time, milking robots increase the consumption of concentrate, and thus the costs of feeding. An increase in the number of somatic cells, reducing the quality of the milk can happen. Combined with the cost of the investment and the installation of the robots, this reduces the final remuneration for 1,000 liters from 70€ to 48€. This loss is compensated by an average increase of 11% in the volume of milk per cow per year (Autellet, 2019; Cogedis, 2019).

Skills acquisition:

Whatever the tool and its cost, training is necessary. Their costs vary between €420 and €1,400 (Idele, 2020).

References:

Autellet, R. (2019). Robotisation en élevage : état des lieux et évolution. Académie de l’Agriculture de France.

Balafoutis, A., Beck, B., Fountas, S., Vangeyte, J., & Wal, T. van der. (2017). Precision Agriculture Technologies Positively Contributing to GHG Emissions Mitigation, Farm Productivity and Economics. Sustainability, 9(1339), 28.

Cogedis. (2019). Le passage en traite robotisée s’accompagne d’une augmentation de la productivité. Plein Champ.

Farm Europe. (2019). Etude des performances économiques et environnementales de l’agriculture digitale.

FIGARO Irrigation Platform. (2016). FIGARO’s Precision Irrigation Platform Presents Major Water and Energy Savings. http://www.figaro-irrigation.net/outputs/the-figaro- platform/en/

Huneau, T., & Gohier, C. (2017). Agriculture de précision robotique et données. In Fermes numériques (Vol. 1, Issue). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Idele. (2020). Idele formation.

IDELE. (2019). Inventaire et tests de capteurs.

http://idele.fr/no_cache/recherche/publication/idelesolr/recommends/inventaire-et-

tests-de-capteurs.html

LITUUS. (2019). Monitoring des bovin au service de la performance.

Soto, I., Barnes, A., Balafoutis, A., Beck, B., Sánchez, B., Vangeyte, J., Fountas, S., Van der

Wal, T., Eory, V., & Gómez-Barbero, M. (2019). The contribution of precision agriculture technologies to farm productivity and the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions in the EU. https://doi.org/10.2760/016263

Weenat. (2020). Communication personnelle.

THE EUROPEAN RECOVERY PLAN: HOW IT SHOULD BE DESIGNED TO BETTER SUPPORT AGRICULTURE

The European Commission has presented an ambitious European Recovery Plan and a new Multi-Annual Financial Framework for the 2021-27 period.

The new proposals bring in new resources for the agriculture sector as compared to the initial proposal of May 2018, although the total amount of support falls in 2018 constant prices by €34 billion as compared to the 2014-2020 period.

The key elements for the sector are:

- “A €15 billion reinforcement for the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Developmentto support rural areas in making the structural changes necessary in line with the European Green Deal and achieving the ambitious targets in line with the new biodiversity and Farm to Fork strategies”

- “An increase of €4 billion for the Common Agricultural Policy (…), to strengthen the resilience of the agri-food (…) sector(s) and to provide the necessary scope for crisis management”

The focus of this paper is on putting forward Farm Europe’s proposals on how best this well-needed resources can be put to use.

– The rural development additional resources should be committed between 2022 and 2024. This should be amended to allow the new resources to be committed as from 2021, as the whole point is to without undue delay help the sector to recover from the current crisis and prepare for the future. The new resources should be part of the 2021 budget and not wait for the implementation of the CAP reform which will not occur before 2023.

– The second proposal Farm Europe wishes to make is to dedicate the €15 billion reinforcement to supporting dual-purpose investments in farms. Those investments should reduce the environmental footprint and at the same time improve the economic situation of farmers.

Examples are investments in digital or smart farming tools and systems, and on production of bio methane from livestock effluents. Those investments squarely qualify for the objectives set-out by the Commission to prepare the sector “making the structural changes necessary in line with the European Green Deal and achieving the ambitious targets in line with the new biodiversity and Farm to Fork strategies”.

– Another proposal is to reinforce the co-financing rates for those investments. The Commission reduced the co-financing rates for rural development actions by 10% in its CAP reform proposal. But the dire economic and financial situation of many farmers and countries calls for a higher rate of community financing to make sure the uptake is optimal. Farm Europe thus proposes that community co-financing should raise to 75%.

Those investments should benefit from the bulk of the new resources, and at least €10 billion be ring-fenced to that purpose.

– The new resources should also contribute to further support crisis management tools, like climatic insurance, mutual funds and income insurance. The EU, with very few exceptions, is poorly equipped with these tools, and the new funds could provide the right incentives to bolster the interest of farmers in using the existing legislative provisions. The main obstacle to the development of crisis management tools in the EU seems to be the cost. The new funds could provide the resources to increase community co-financing and thus render these tools more attractive.

– The €4 billion new resources for the CAP Pillar I are clearly earmarked for crisis management. This makes it possible to finally create and adequately fund a Crisis Reserve, as Farm Europe has put forward in previous papers and initiatives, and the European Parliament Comagri has proposed. €1.5 billion should be committed to the new Crisis Reserve as from 2021. The Crisis Reserve should have the

mandate and the resources to quickly redress markets, intervening at early stages and without delay with a wide range of emergency measures.

– The remaining resources should be used to support the sectors that are already suffering from the Covid-19 impact. Support actions should be agreed to swiftly rebalance hard hit markets, e.g. in the wine, beef and sheep and goat sectors.

It is of crucial importance to swiftly mobilize the additional resources as from 2021. It would be unwise and contrary to the key objective of the European Recovery Plan to wait for the adoption of the CAP reform, and the subsequent presentation of the Strategic Plans. That process would mean simply and squarely two years lost whilst the crisis hits harder.

Farm Europe believes that the European Commission Recovery Plan, although still coming short on the budget for the sector, offers a unique opportunity to shape the response to the Covid-19 crisis and prepare the sector for the European Green deal – provided it is well designed.

THE EU NEEDS A NEW AGRICULTURE TRADE POLICY

The impact of the Covid-19 crisis is still unfolding but one lesson can already be learned – we need food security.

In some strategically important sectors the lack of domestic availabilities became quite acute, but fortunately agriculture in the EU assured its fundamental role of feeding its citizens.

It did not pass unnoticed that in the crux of the crisis many countries resorted to export bans and restrictions, including in the agri-food sector. What would have happened if the EU was as vulnerable in food supplies as it was in some medical equipment?

Contrary to countries that have imposed restrictions on their food exports, the EU as a whole ensured also its share of world supplies. This is not a minor or side element, as food scarcity is a real risk in many poor areas of the globe, and first and foremost in neighbourhing Africa.

The time has come to review the EU trade policy, in particular on agriculture, at the light of the past experience and the lessons of the Covid-19 crisis.

In a nutshell the current EU trade policy might be depicted as willing to strike as many Free Trade Agreements (FTA) as possible with as many countries as possible.

The underlying assumption is that the EU, and her trade partners, benefit from freer trade that expands wealth. Agriculture is always part of the FTAs as required by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

Another strategic element underpinning the EU trade policy is the belief that freer trade under the umbrella of international rules is a key element of globalization, and a means of reducing strategic fault lines and improving a cooperative approach to planetary issues.

This global approach has resulted in the European Commission (EC) overlooking an in-depth analysis of the impact of each FTA, and failing to decide on its own merits. The EC impact assessments systematically rely on global evaluations and ignore the specific impacts in specific sectors.

This has been particularly acute in the agriculture sector. Agriculture and food security concerns have not been front stage. There has been some recognition that highly vulnerable agriculture sectors (typically beef, sugar, and to some extent pork) should not be fully exposed to outside unfettered competition, but never to the point of stopping short of constantly increasing EU’s market access, or helping those sensitive sectors cope with increased competition. Other sectors, like sheep and goat meat, have been largely left on their own whilst their economic situation has worsened with increased imports.

Farm Europe argues that the time has come to adopt a more balanced trade policy. After Covid-19 we need a change of policy that does not compromise food security. We need a better balance between the benefits of freer trade and its asymmetric negative impacts. We need less of an ideological driven policy and more pragmatism and realism.

Farm Europe is not against trade, nor negotiating FTAs for the benefit of producers and consumers. It must be recognized that FTAs bring benefits that should be cherished.

The EU is a lead net-exporter of agri-food products. In 2019 the export value of agri-food products came to a total of €151.2 billion, while imports accounted for €119.3 billion. The trade surplus reached an all-time high of €31.9 billion. It is undeniable that trade brings wealth and jobs to the sector.

Isolation within our borders would bring less production, lower farm revenues, less jobs, fewer agri-industries, slower technological progress and innovation spurred by international competition.

Without EU agri-food exports, food security in many countries, and in particular in Africa, would be compromised. As demand for food is raising, the role of the EU as a lead world exporter is paramount.

However FTAs should not compromise the viability of the more vulnerable sectors. FTAs have brought winners and losers in agriculture, and the losers have been basically left alone to cope with the consequences.

In addition to that, the trade surplus of the EU on agri-food products masks the fact that the EU surplus in raw agriculture products is small, the overall figures are largely helped by the EU export performance on processed products, in particular of high-value.

Whilst FTAs have somehow shielded the most sensitive sectors by limiting free trade under quotas, the accumulation of FTAs, amongst other factors, is leading to shrinking vulnerable sectors like beef and sheep and goat meat.

A new trade policy should pursue the benefits of freer trade whilst either completely shielding vulnerable agriculture sectors, or adopting specific programmes to help those sectors cope (and provide mandatory EU resources to fund those programmes).

The EC should in its prior assessment to engaging in FTA negotiations carefully evaluate the degree to which borders could be open in key sectors, and integrate in its assessment as appropriate the design and resources needed to help those sectors cope with additional external competition.

A new trade policy should respect a level playing field between EU and third countries, with regard to environmental, sanitary and phytosanitary constraints.

Whilst it is true that imports into the EU must respect the EU’s sanitary and phytosanitary norms, in many exporting countries substances prohibited in the EU are widely used. The level of controls at our borders must raise to these dangers.

On the environmental field the situation is even worst. Existing FTAs only have some clauses that embed adherence to UN conventions.

The fact is that the EU imports a wide range of produce from deforested areas, from beef to palm oil. This is unacceptable as the EU thus becomes an active actor in deforestation through its large demand for those products. The EU should adopt a clear cut trade policy that bans imports from deforested and other previously high-environmental value areas. The EU has the independent means to control deforestation and identify which products originate in those areas, and should not leave certification of deforested products to third countries or other parties. The EU should establish a clear cut-off date in the past for accepting imports from previously deforested and high-environmental value areas, banning all imports from areas degraded after that date.

The EU environmental constraints are the more stringent in the world. That comes at a cost for the sector, and that cost is not borne by its competitors. In particular the EU should not accept that imports of agri-food products that were produced under significantly lower environmental constraints benefit from tariff advantages.

The level playing field in new technologies is also being turned against EU agriculture. The EU is banning the use of promising techniques that have the potential to increase productivity and reduce the environmental footprint like New Breeding Techniques. By its own doing, the EU is putting the sector at a competitive disadvantage.

On labour conditions the level playing field is all but absent. Existing FTAs only embed adherence to ILO conventions.

Although this is typically a cross-cutting issue that goes further than agri-food trade, FTAs could have provisions to address minimum wage issues in particularly sensitive sectors. For instance, on meat trade the cost of operating slaughterhouses is significant and thus the issue is relevant to establishing a level playing field.

Another cross-cutting issue is competitive currency devaluation. There is a strong case to insert clauses in FTAs that counter competitive currency devaluations. A currency devaluation has quite often a larger impact in trade terms than tariffs, and monetary policies that intentionally devalue a currency should be countered by counter-measures, e.g. by giving the other party the possibility to raise tariffs.

The trade policy changes that Farm Europe puts forward should be seen in the context of reforming the EU trade policy in agriculture towards a more pragmatic and realistic course.

The new policy should bring coherence and a holistic view of trade costs and benefits. On agriculture, it should be in phase with the model of agriculture pursued in the EU, largely based on medium sized family farms operating under their own limited capital resources, on and how the EU is prepared to support this model.

THE US LAUNCHES A THIRD LAYER OF COVID-19 SUPPORT TO AGRICULTURE

Readers might think that they have already read about this, but the fact is that in the US a new layer of support to help agriculture cope with the Covid-19 crisis was launched this week. This support package is the third since the beginning of the crisis, so yes you have read about increased support in the US but you’ve not read about the latest.

This package consist of an additional $ 470 million for commodity purchases, financed by customs revenues. The biggest share goes to dairy products with a $ 120 million allocation. Potatoes, turkey, chicken, pork, come after in a long list that includes a variety of fruits and some fish products.

It is worth recapping how much support US farmers have had so far to cope with the Covid-19 crisis. First came an increase of the main support programmes war chest of $ 14 billion. Second a $ 19 billion package consisting of $ 16 billion direct payments and $ 3 billion commodity purchases. And latest the $ 470 million this week package. In total a staggering $ 33.47 billion, or slightly more than 30 billion euros.

In the EU? The specific Covid-19 support package is estimated worth a paltry 80 million euros.

Comparing per farmer and per hectare Covid-19 support in the US and in the EU, in euros, says it all:

- US: €15 415 per farmer; €73 per hectare

- EU: €8 per farmer; €5 per hectare

THE COVID-19 CRISIS AND EU AGRICULTURE: WHAT WE NEED AND WHAT WE DON’T NEED

In all major crisis there is a moment of denial, a moment of blame and a moment of reckoning. We are experiencing a major and unprecedented crisis, a crisis on which states decided to stop economic activity to protect lives. Unfortunately we see many still in denial of the inevitable impact on agriculture.

Farm Europe has written about the likely impact of the Covid-19 crisis in agriculture markets, and what should be done to anticipate the shock.

Here we want to look forward and contribute to what should be the comprehensive response of EU agriculture policy, and what should be avoided at all cost at this stage.

The European Commission indicated her willingness to revise the MFF, the multi-annual budget proposal. You will recall that the CAP was badly treated in the original proposal, with real budget cuts of 12% over the 7-year period.

The current crisis has however showed one thing: we need food security. Some third countries have announced food export restrictions. What would have been the situation in the EU if we were short of food supplies?

Farm Europe agrees with those who point out that food security cannot be delegated, and that the CAP is not a policy only for farmers but rather a policy to the benefit of EU citizens.

Food security is not achievable at local level, only an EU-wide approach will deliver. We are not advocating a narrow and misguided concept whereby each county or region should be self-sufficient, because it is simply not feasible nor desirable. Only at a larger level like the EU, with a functioning internal market, can we achieve actual food security. We are also not advocating that the EU should not trade with the rest of the world, as we can benefit from trade and enjoy its economic benefits without compromising food security.

We also need a reversal of the unfavourable treatment of agriculture in the EU budget proposal. The EU agriculture has been the bedrock of food provision to European citizens even when most of the economy is idle. It is however facing hardship due to reduced demand and demand shifts, as a result of commerce shutdowns, and in the near future reduced purchasing power of many Europeans and world consumers. The last thing EU agriculture needs is further cuts in support. When life lines are extended to whole parts of the economy it would be unaccountable to reduce support to agriculture.

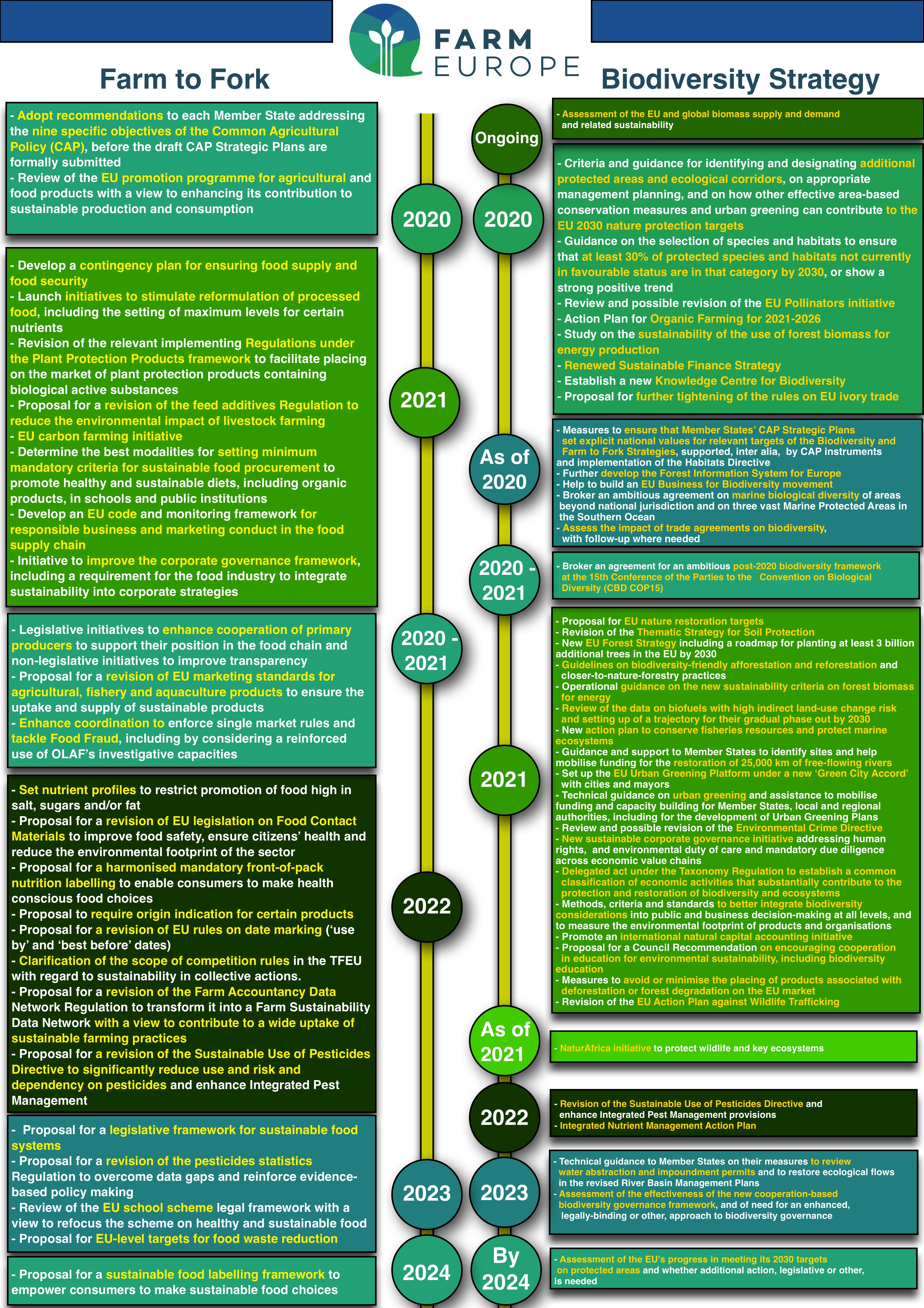

By contrast what we don’t need is a set of policies that increase the burden of producing food in the EU. We don’t need a Farm to Fork Strategy, or a Biodiversity Strategy, that only increase restrictions on the use of inputs, that reduce the agricultural area and productivity, and that reduce already stretched farmer’s incomes.

Farm Europe wishes to be crystal clear: we believe that EU policies should contribute to further environmental protection and to fight climate change. But that has to be done hand-in-hand with furthering the economic situation of farmers and assuring food security.

Increasing the land set-aside for biodiversity goals to 10% and organic production to 30%, as some propose, would reduce the EU production of food by a staggering 15%. Reducing pesticide and fertilizer use without providing farmers with the investments and the technology mix to achieve meaningful environmental goals will result in further food reduction and economic distress for farmers. That is not acceptable.

Thus the second logical “what we need” is a package to promote the right investments in agriculture, those which reduce the environmental foot print and greenhouse gas emissions and at the same time keep or expand agriculture production, ensure food security and sustain farmer’s livelihoods.

We also need to strengthen the resilience of the sector. As Farm Europe has been consistently advocating, and the European Parliament COMAGRI has taken the lead in proposing, we need a well-financed crisis reserve in the CAP that would have the means and the mandate to quickly intervene in times of crisis, by making use of exceptional measures and shoring-up insurance and mutual funds.

This Covid-19 crisis will leave its scars for some time and we need to learn from past experience that showed that the current CAP crisis management tools are not good enough. The latest dairy or fruits and vegetable crisis are witness to the problems we faced in the past, at great economic and budgetary cost.

What we don’t need is to wait-and-see, to seat back and wait for the crisis to unfold in the dairy, beef, wine, fruit and vegetable, sugar, ethanol or any other sector. The flower and ornamental plants producers are already facing tremendous hardship. Farm Europe calls on the decision-makers, and in particular on the European Commission to change gear and become proactive rather than reactive.