The national debates that took place during the European elections will now converge to Brussels. The 720 elected MEPs who have made commitments in each of their countries will arrive with a patchwork of ideas. It will now be a challenge to transform those ideas into a common programme and a collective vision for agriculture. See also our infograph of the new European Parliament below.

Almost all the national debates have been marked by the strong presence of agricultural issues. This is reflected in the election manifestos, most of which address agricultural, food and environmental issues. Building a common path will therefore be a responsibility for the future European Commission and, in particular, the future European Commissioner for Agriculture, who will have to build a strategy for action.

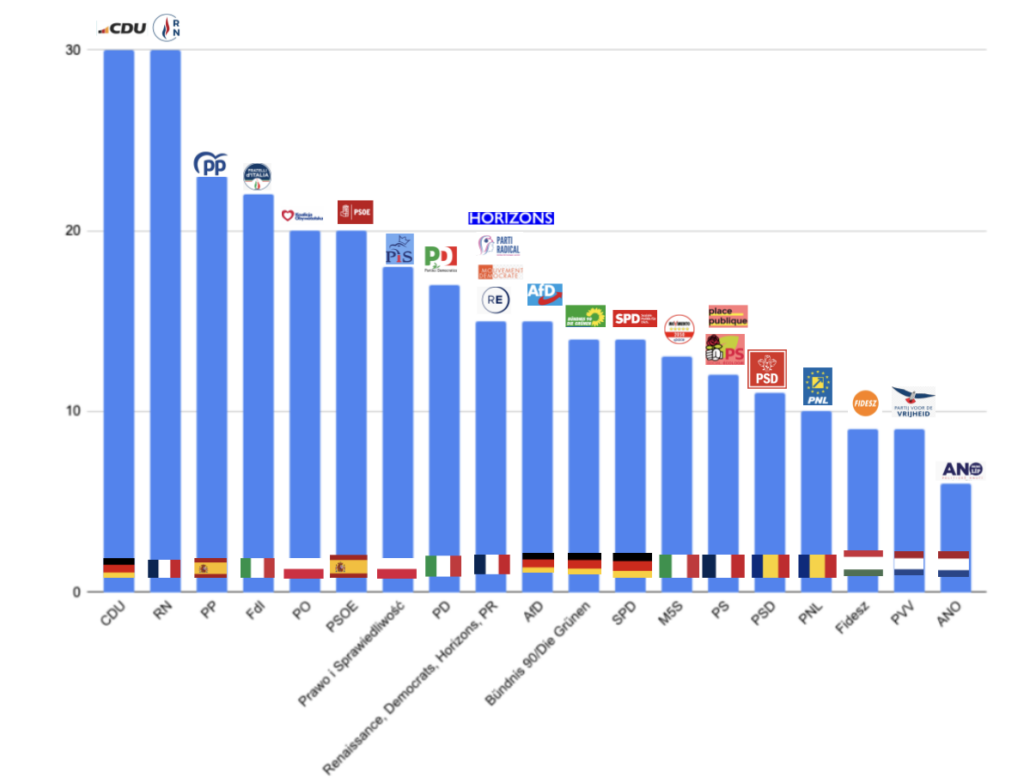

An analysis of the electoral platforms of the 20 largest delegations reveals fault lines and points of polarisation, but also possible ways of overcoming differences to build a collective vision in the general European interest, for farmers, citizens and consumers.

Green Deal or no Green Deal

The divisions inherited from the extreme polarisation around the Green Deal, Farm to Fork and the large-scale agricultural protests of late 2023, early 2024 in 17 EU countries are reflected in particular in the manifestos of socialists, ecologists and the far right movements, some of whom formally call for “pursuing the ambition of the Green Deal” and Farm to Fork, others of whom formally call for rejecting this path.

The German AFD, the Dutch PVV and Orban’s Fidesz are categorical calling to “get out” of the Green Deal, a path that is “destroying European agriculture”. Similarly, Poland’s PiS is particularly hostile to the Green Deal, which “harms Polish agriculture and risks leading to its disappearance”. This party is one of the few to also explicitly mention the threat posed by competition from Ukraine. Conversely, the German SPD, like the French and Italian Socialist Parties, is calling for the Green Deal to continue to be implemented and for its ambitions to be translated into concrete regulations. The Spanish Socialist Party is much more cautious in the wording, as are most of the other political forces, which prefer to avoid the words of Green Deal and focus instead on more specific topic.

Less bureaucracy, more pragmatism

The centre and right-wing parties are calling for pragmatism and dialogue, as is the case in particular with the CDU, which is taking up the theme of strategic dialogue. It wants this process to be pursued in an open manner. It is on the side of incentives rather than prohibitions to make progress on environmental issues. The Spanish PP is calling for “common sense”, “realistic” deadlines and decisions based on “science”.

On the centrist side, without mentioning the Green Deal, some delegations refer to important texts provided for by this strategy, following the example of Renaissance. The ANO party stresses its desire to reject demagogic approaches to reconciling food production and the environment, focusing on solutions such as biocontrol.

In the detail of the measures, with the exception of the radical right-wing parties, no one is questioning the current regulations, but rather the need in the future not to add bureaucratic overload.

Community preference, mirror clauses and the fight against fraud.

A recurring theme, driven in particular by eurosceptic groups, but widely taken up by all political forces, is that of “local preference” for Renaissance, and the promotion of the “principle of reciprocity” for Fratelli d’Italia. In the same direction, many political forces are calling for a new approach to trade. The Spanish PP is calling for the introduction of “mirror clauses”, a theme now shared by all. The Five Star Party, which has a particularly detailed agricultural and food programme, is committed to promoting “Made In” products and defending geographical indications. For its part, the Polish civic platform has a strategic food production objective, with half of the products to be the subject of genuine Polish food sovereignty, and the creation of local markets.

A strong idea emerged around the control of imports, with the idea of a health and environmental control agency supported by Renaissance in France, but also by the Five Stars in Italy. Like other delegations, the Rassemblement National has also made the fight against fraud, particularly in the agricultural sector, one of its priorities.

Risk management and environmental services

The issue of income volatility and the need for protection against climatic hazards is a recurring theme, from the Mediterranean left (Italy and Spain) to the German right (CDU). The CAP must ensure a decent income for farmers, with a strengthened economic pillar for the CDU, while rewarding environmental services, tracing a line for the future around risk and crisis management, and green payments. In Poland, too, the theme of a stabilisation fund is being promoted by the Civic Platform.

The Italian Socialists (PD) also stress the importance of income stabilisation tools and mutual funds in particular. The Spanish members of the same group are calling for actions to combat market volatility. The French socialists have a singular approach, with their desire to move away from per-hectare aid and the theme of minimum prices.

Branch organisations and the European “EGALIM” initiative

In the wake of the agricultural movements, the question of the distribution of value and unfair commercial practices is a strong theme, also in connection to market volatility. Like the French Socialist Party, the Spanish Socialist Party has made this a central issue, stressing the importance of producer organisations and cooperatives. For the French Renaissance delegation, the challenge is to anchor the theme of transferring the national EGALIM law on value sharing to the European level. The Italian Socialists, on the other hand, prefer to stress the importance of “fair prices” for agricultural products and their desire to tackle the problem of sales below production costs, combat unfair practices, promote transparency and enhance the value of local products.

Animal welfare and pesticides

Two issues emblematic of the tensions at the end of the 2019-2024 term of office were raised by most of the delegations, either to request their extension or, conversely, their abolition.

Several delegations from the left and centre are calling for a new initiative to reduce pesticide use by 50%, some of them also calling to promote biocontrol products. The German Greens do no mention specific targets, but they are putting forward the idea of a tax on pesticides and the polluter pays principle for manufacturers. The German Socialists, like the Italian Democratic Party, have confined themselves to calling for a “significant reduction”. The CDU, on the other hand, wants to “oppose excessive rules on the use of pesticides”. It is likely that pressure will be brought to bear on the Commission to resubmit a proposal on pesticide reduction, given that the issue is currently regulated by the SUD Directive dating from 2009 and that certain issues, such as new rules to facilitate biocontrol and strengthen integrated pest management, are rather consensual.

Similarly, the issue of animal welfare has been taken up by Renaissance in France, the Italian Democratic Party, the German Greens, the Spanish Socialists and the Five Stars. Conversely, the Fratelli d’Italia delegation believes that these issues should be taken up at national rather than European level. More specifically, the Dutch VVD has made a ban on the production and import of furs a theme of its campaign, as well as a ban on cages in livestock farms, a theme also supported by the Five Star movement in Italy.

Carbon, innovation and investment.

The promotion of innovation is a cross-cutting theme on most of the lists, with notable nuances such as the German Greens, like most of the major delegations of the Socialist Group, which defend the widespread use of digitalisation and precision agriculture. However, most of these delegations are cautious when it comes to genetic selection, not mentioning this point or, like the German Greens, rejecting patents on plants and animals and emphasising the precautionary principle. All want to increase funding for research and innovation, with a particular emphasis on organisational rather than technical innovation. The German Socialists are calling for “careful and comprehensive assessment” and “freedom of choice for consumers” through traceability and clear labelling. The French Renaissance group is in favour, particularly in view of the objective of reducing the use of pesticides.

The centre and the right are strongly in favour of innovation and investment as a priority, particularly the Dutch VVD, through regulations that favour “innovation, efficiency and sustainability”, “without unnecessary bureaucracy”.

Lastly, the issue of climate change and carbon comes up many times, either in the international context, with the Rassemblement National in France calling for the introduction of a “real carbon tax”, or the Italian Five Stars calling for the full application of the CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism), or on a more internal level to reward farmers for their efforts to reduce emissions or store carbon.

In particular, the Spanish PP would like to set up an incentive mechanism to remunerate farmers and landowners for storing and reducing carbon emissions. Other delegations, notably the Civic Platform, are making the restoration of peatlands a priority, as are the German Greens, who want to “reintegrate them into the CAP” and “transform soils into CO2 sinks”.

Labelling, synthetic and alternative products

A fierce debate is emerging, with the German Greens and the Italians from Fratelli d’Italia at opposite ends of the spectrum. The German Greens are now openly calling for “support for research and development into fermentation and cell culture for the production of sustainable food”, while the Italians are stressing the importance of continuing the fight against the production and marketing of synthetic meat and food. The Dutch VVD also advocate the development of “alternative proteins”.

Similarly, the Nutriscore is being rejected by Fratelli d’Italia, but also by the Spanish PP, which is calling for a nutritional information system that avoids misleading consumers. The PP believes it is necessary to promote healthy meat consumption and defend the sector against attempts to criminalise it.